The ‘Push and Pull’ Factors of Distributed Leadership: Exploring Views of Headteachers across Two Countries

1University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

2Dolly Memorial School, Ghana

Abstract

Governments and other stakeholders in education are beginning to recognize the important roles school leaders can play in school development and efforts are being made to allow them to become more involved in managing schools. However, despite these efforts, head teachers are challenged with the perfect leadership style to improve schools. Many scholars have lauded the positives of distributed leadership as one if not the best leadership for school improvement. This study sought to explore distributed leadership across primary schools in Accra-Ghana and Northampton-UK. The study adopted the explanatory sequential mixed method design. In this design, face-to-face interviews and non-participants observations were employed while closed ended questionnaires were given to 65 head teachers and 10 out of the 65 head teachers were sampled and interviewed. Two schools were purposive sampled and observed. The findings of the study revealed that head teachers from both countries understood the concept of distributed leadership as giving leadership opportunity to other teachers to meaningfully accept and take full responsibility for their leadership roles. Despite these findings, head teachers from the two countries have their own style of distributing leadership in the school. Admittedly, head teachers echoed that team work and trust is a necessity for effective and successful distributed leadership in schools. Notwithstanding these benefits of distributed leadership, head teachers from both Northampton and Accra are confronted with some challenges such as who should be involved and to what extent. The researchers recommend that head teachers should find ways of giving freedom to teachers who have the requisite expertise and ready to lead particular areas of the school even if it is for a shorter time. Additionally, a well-structured programme of high quality in-service training should be developed and offered to every head teacher and teacher in order for every school to develop appropriately.

Keywords: Distributed leadership, School improvement, Push and pull.

1. Introduction

Distributed leadership in education has become one of the key issues in Ghana’s education development agenda. Ghana like any other African country has initiated a number of reforms in the past, the latest being the 2002 Educational Reforms and the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) to improve quality of teaching, learning and participation. In order to achieve these expectations, Oduro (2007) argues that for schools to improve, distributed leadership should be encouraged and teachers should be involved in decision-making activities which are the key to the successful implementation and achievement of these policies. Numerous studies (Oduro, 2007; Harris, 2013; Lizotte, 2013; Dampson, 2015) have proved that school leaders can make a change in school and student achievement, if teachers are allowed the ability to make meaningful opinions. However, autonomy does not inevitably lead to development unless it is well sustained. The obligations of head teachers in schools, according to the OECD (2001) should be defined through an understanding of the practices most likely to improve teaching and learning. In this context the researchers opine that distributed leadership which is primarily concerned with shared, collective and extended leadership that builds the capacity for change and improvement is the key to effective practices in schools.

In Ghana and other African countries, effective school leadership has become necessary in order to address global education agenda (Oduro, 2004; Wadesango, 2011). This is very important because scholars such as Jones and Harris (2013) argue that the importance of distributed leadership is a potential contribution to positive change and school improvement.

The concept `distributed leadership’, in turn, attracts a range of meanings and is associated with a variety of practices. Mayrowetz (2008) states that different uses of this term have emerged and refers to distributed leadership as “an emerging theory of leadership with a narrower focus on individual capabilities, skills, and talents” that focuses on a joint responsibility for leadership activities. According to MacBeath (2005) distributed leadership means the same as dispersed, shared, collaborative and democratic leadership. In this study distributed leadership is where head-teachers share leadership responsibilities among teachers to participate in all school activities. These definitions are summed up by Harris (2013) as mobilising leadership expertise at all levels in the school in order to generate more opportunities for change and to build capacity for improvement.

There is no doubt that the practice of distributed leadership in schools goes with numerous prospects. Various studies conducted in both developed and developing countries by scholars such as (Danielson, 2006; Spillane, 2006; Abu, 2010; Wadesango, 2011; Harris, 2013). Danielson (2006) confirm the numerous prospects of distributed leadership in Schools. For example Danielson conducted a study and found 2 broad categories of the benefit of distributed leadership, namely cultural and structural development benefits. Leithwood et al. (2009) assert that the difference in high and low performing schools can be attributed to different degree of leadership distribution.

It is possible that distributed leadership could support the abuse of power (Mayrowetz, 2008). Teachers can become overstressed by shared decision-making and the benefits of participation do not necessarily accrue to better teaching practice or to the benefit of the school as a whole, especially if teachers’ and organisational goals are not well aligned (Mayrowetz, 2008).

Distributed leadership for efficiency and effectiveness has been contested. While some advantages and benefits have been outlined, there are also risks that distributing leadership will not add to school improvement. Leithwood and Jantzi (2000) found that “higher scores on total or distributed leadership in schools, defined as both teachers and principals engaging in leadership work, have actually been associated with lower levels of student engagement.” Timperley (2005) concluded that “distributing leadership is a risky business and may result in the distribution of incompetence”.

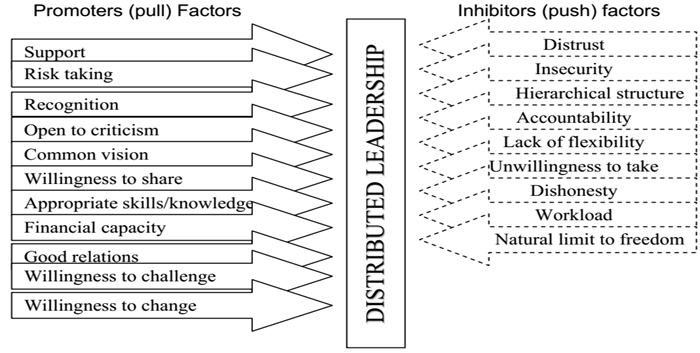

A study conducted in Ghana by Oduro (2004) revealed that practice of distributed leadership in schools may be promoted or inhibited by both internal and external forces which he termed them as 'pull' and 'push' factors. He noted that the 'pull' forces are those which tend to make distributed leadership favourable and attracted to head teacher, whereas, the 'push factors are those which frustrate and do not allow head teachers distributed power fairly to teachers. These factors are shown in the diagram below.

Diagram-1. The Pull and Push factors

Another study conducted by MacBeath (2005) in the United Kingdom revealed that one of the major challenge of distributed leadership is the accompanied pressure from work load. He stressed that the burden of workload on teachers tend to have a negative effect on their work performance and ethics. Although this may sound contradictory to the benefit of distributed leadership, studies have shown that distributed leadership goes with workload.

Another major 'challenge to distributed leadership is the bureaucratic and hierarchical structures that exist in schools. In MacBeath's study, head headers interviewed indicated that they find it difficult to distribute leadership because of the bureaucratic and hierarchical structures which inhibit the implementation of distributed leadership. MacBeath further advise that for head teachers to deal with the bureaucratic and hierarchical structures, they need to adopt strategic distribution which places emphasis on people as team players rather than individual competences and favouritisms. Hargreaves et al. (2010) and Hargreaves et al. (2014) confirm that one of the major challenges of distributed leadership in the accountability and responsibility of leadership.

Similarly, study conducted by Abu (2010) revealed that teachers lacked an understanding of the concept of distributed leadership despite being practised by their head-teachers whiles Lizotte (2013) also reported that most teachers have high feelings of incompetence and felt unprepared to lead their colleagues since most of them were trained to be members and not team leadership. In short, distributed leadership comes with it benefits and challenges.

From the ongoing discussion the 'push' factors seem stronger than the 'pull' factors, it imperative to note that in practical distribution of leadership in schools, the 'push' factors make it difficult to succeed. Although distributed leadership have so many prospects, most of the problems which has made it difficult to succeed in schools are the 'pull' factors such as dishonesty on the part of teachers, too much workload, flexibility, bureaucratic and hierarchical structure plays a major hindrance in its success. Many studies have been conduct on distributed leadership, however, little empirical studies have been conducted across countries.

Thus, this research strives to explore factors that facilitate or prevent teachers in Ghanaian and UK Primary Schools from using distributed leadership and ways by which distributed leadership affect school improvement in both settings. Additionally, the study also looks at the extent to which head teachers in Ghanaian and UK Primary Schools perceive and adopt distributed leadership as a tool for school improvement.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

The study adopted the mixed method approach where the researchers used both qualitative and quantitative tools to collect data. Given the study’s emphasis on the push and pull factors the researchers adopted the sequential explanatory mixed method design which fits into the three phases of data collection (Creswell, 2012). The rationale for this approach was to use quantitative data and results to provided a general picture of the research problem, more analysis and specifically use qualitative data collection to refine and explain the general picture.

In this design, the researchers first collected and analysed the quantitative (numeric) data. The qualitative (text) data were collected and analysed after obtaining the quantitative results. In order to address the research questions set out by this study, the study was designed in three phases. In each phase the researchers adopted specific research tool(s) to answer the research questions. Phase one of the study was designed to collect data from respondents in a survey using a close-ended questionnaire. Phase two employed semi-structured interview to elicit responses from participants, while in phase three a case study approach was employed through the use of micro-ethnography/participant observation (Bryman, 2012) to garner data to support the findings from the questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews in phases one and two. The quantitative data was analysed using simple frequency counts (percentages) to rank the responses while the qualitative data (semi-structured interviews) was analysed using the thematic analysis. The analysis and results obtained from both the close-ended questionnaire survey from phase one was used to develop a semi-structure interview guide for phase two. In phase three, the findings from phase one and two were used to select a school each from Ghana and UK for observation.

2.2. Sample and Sampling Procedure

Keeping in mind issues arising with access to schools and given the geographical terrain of Ghana and related transport barriers the population for the study was limited to 17 primary schools in Accra (Ghana) and 16 in Northampton (UK) with a total number of thirty-three (33) head-teachers and thirty-two assistant head-teachers (32). In all 33 primary schools were involved in the study. As this study is information-rich the researchers employed census sampling technique to select all head-teachers and their assistants. The participants were selected as they could best help the researchers understand the phenomenon that is being investigated (Creswell, 2012). In Northampton and Ghana each primary school have a head-teacher and an assistant. Using the census sampling, seventeen (17) head teachers and their assistants (17) from Accra-Ghana and sixteen (16) head-teachers and their assistants (15) from Northampton were sampled to answer the questionnaire. During the second phase of data collection, the simple random sampling technique was adopted to select 5 head-teachers each from Accra-Ghana and Northampton-UK and were interviewed. Purposive sampling was then employed in the third phase to sample a school each for observation based on the outcome of the interview. The analysis from the interview data were used to select two schools for observation.

2.3. Instrumentation and Data Collection

Three instruments (closed-ended questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and participant observation) were used to collect data from head-teachers and their assistants. The purpose of analysis is to describe or explore data, to test a hypothesis, to seek correlations, to identify differences between two or more groups and to look for underlying groupings of data (Cohen et al., 2011). In analysing quantitative data, Bryman (2012) and Cohen et al. (2011) suggest that selecting a statistical test to be used depend on the scales of data being treated (nominal-ratio) and the task which the researchers wishes to perform – the purpose of the analysis informed the researchers to use simple percentages. The researchers transcribed all the interviews, read, reread all the transcript. The researchers further analysed the transcripts by coding using thematic approach. Field notes were taken during the observations and were also analysed using thematic approach.

Ethical consideration such as access and consent, confidentiality and anonymity, rights, safety and well-being of participants and the researchers were all considered before, during and after the research.

3. Findings

The successful implementation of distributed leadership involves the push and pull factors discussed in the introduction. The findings of this study were perceived to have linkages with the practicality of these factors. The quantitative data sought to explore the similarities and differences that exist between the 'Pull and Push' factors among the two countries. Head-teachers and assistants from both countries were asked to rank the pull and push factors as shown in Table 1 and 2.

A total of 65 head teachers and assistants answered the questionnaire, thirty-four (34) from Accra-Ghana and thirty-one (31) from Northampton-UK. Admittedly, all the participants agreed that the practice of distributed leadership goes hand in hand with some challenges and benefits that are related to the push and pull factors. Table 1 shows how head-teachers from the two countries ranked their benefits (pull).

Table-1. The Pull Factors

| Pull Factors | Head-teacher/assistants (Northampton) | Head-teacher/assistants (Accra) |

| Common vision | 96.7% (rank 1) | 67.6% (rank 5) |

| Willingness to share | 83.8.% (rank 2) | 61.7% (rank 6) |

| Support for each other | 80.6% (rank 3) | 76.4% (rank 3) |

| Financial capacity | 77.4% (rank 4) | 73.5% (rank 4) |

| Good relations | 74.1% (rank 5) | 88.2% (rank 2) |

| Recognition | 61.2% (rank 6) | 94.1% (rank 1) |

Source Field data (2017)

Table 1 shows the pull factors that facilitate distributed leadership in both countries. Interestingly, there are differences in the pull factors across the two countries. Data analysed using simple percentages indicate that majority of the head-teachers in Northampton perceived common vision, willingness to share and support for each other as the most important factors that facilitate distributed leadership in schools with recognition being the least. Contrary, head-teachers in Accra-Ghana perceived recognition, good relation and support for each other as the most important factor that facilitate distributed leadership. These findings which also emerged from the interviews supported by observations made by the researchers imply that head teachers in Accra, Ghana are to some extent unwilling to share power as a result of fear of losing their positions through mistakes whiles conditions in Northampton schools makes is more easy for headteachers to distribute leadership. It is equally important to note that geographical location, code of ethics, individual leadership style and resources available play important role in facilitating distributed leadership in schools, specifically in Accra.

It is evident from this study that distributed leadership goes with numerous benefits such as common vision, develops individual capacity, and shared decision-making. However, the researchers argue that these benefits are more contextualized rather than applicable in all situations and context. Literature on distributed leadership by (Danielson, 2006; Spillane, 2006; Jones and Harris, 2013) is consistent with the findings of this study that the practice of distributed leadership in schools goes with numerous benefits but however failed to contextualize the benefits revealed in this study. In this context Hargreaves et al. (2014) argue that when distributed leadership works, individual are accountable and responsible for their leadership actions, new leadership roles created, and there is collaborative teamwork. Similarly, Oduro (2004) also found that head teachers who practice distributed leadership in Ghanaian basic school tend to improve teacher involvement in school decision-making. The interviews and observations conducted by the researchers confirmed that head-teachers who practice distributed leadership experienced collaborative and collegial school environment as argued by Hargreaves et al. (2014).

Recounting his experiences, a male head teacher from United Kingdom (Male Head Teacher, UK2) said:

I think the benefits are huge because if you are there on your own and you are making the decisions, that is only your mind and your way of doing things and also lots of research has shown that if there is dialogue between people; if people pass ideas of each other, there is coalition approach to things, then the results are better.

A male head teacher from Ghana (Male Head Teacher, GH4):

It helps working in a team to achieve your objectives by accepting the cultural values of our school. If you have vision, it helps you to realize it and it creates a serene atmosphere for effective work to go on.

These responses from the head teachers indicate that the prospects of distributed leadership are categorized in three main themes namely: cultural conditions, structural conditions (Danielson, 2006) and capacity building (Harris, 2002). According to Danielson (2006) there are three aspects of a school’s culture that promote the emergence of teacher leaders; a culture of risk taking, establishing democratic norms and treating teachers as professionals. The researcher argue that it is imperative for head-teachers to convey and assure to all the staff members that the environment in which they are operating is safe to take their professional risks. This suggests that there are no penalties for mistakes as such mistakes will provide insights into how new ideas can be tried and modified.

Table 2 below shows how head-teachers from the two countries perceived the factors that prevent them from using distributed leadership in their schools.

Table-2. The Push Factors

| Push Factors | Head-teachers/assistants (Northampton) | Head-teachers/assistants (Accra-Ghana) |

| Hierarchical structure | 96.8% (rank 1) | 64.7% (rank 6) |

| Workload | 93.5% (rank 2) | 97% (rank 1) |

| Dishonesty | 77.4% (rank 3) | 73% (rank 5) |

| Distrust | 74.1.% (rank 4) | 91.2% (rank 3) |

| Insecurity | 70.9% (rank 5) | 88.2% (rank 4) |

| Accountability | 64.5% (rank 6) | 94.1% (rank 2) |

Source: Field data (2017)

As demonstrated in Table 1, there were differences in the perceived factors that hinder the use of distributed leadership. Majority of the head-teachers from Northampton-UK perceived Hierarchical structure, workload and dishonesty as the main push factors with accountability being the least. Contrary head-teachers from Accra-Ghana perceived the push factors as workload, accountability and distrust with Hierarchical being the least.

These findings between the two countries implies that although other push factors such as distrust, insecurity and dishonesty play vital role, the hierarchical structure with its bureaucratic nature which comes with it heavy responsibilities makes head-teachers desist from using distributed leadership in schools.

The researchers therefore argue that despite the efforts made by head-teachers to embrace distributed leadership they knew the workload that accompany leadership and its associated roles and tasks is time consuming. It is interesting to note that data collected through interview revealed that all the head teachers in the Northampton primary schools were concerned that distributed leadership may result in delaying tactics, high tariff with accountability within the school. They were passionate that in distributed leadership, the head teacher remains answerable for all decisions made. A male head teacher (2) from Northampton narrated:

“There is such a high tariff with accountability with people’s progress. If we don’t achieve these targets within the expectations, then the people within the staff room don’t feel that it won’t worth the same people that are getting the distribution of the leadership.”

All the head teachers in Ghana expressed concerns in situations where distributed leadership delays certain activities due to the collaboration and involvement of individual initiatives furthermore; workload was seen as the major push factor in distributed leadership in Ghanaian basic schools which in turn serve as a stressor to teachers.

These findings from the study confirm and are consistent with the findings of Mayrowetz (2008) who established that through distributed leadership, teachers can become overstressed by shared decision-making and the benefits of participation do not necessarily accrue to better teaching practice or to the benefit of the school as a whole, especially if teachers’ and organisational goals are not well aligned. Furthermore, Harris (2004) outlines some additional difficulties which are consistent with the findings of this study. She argues that because the bureaucratic structures that exist in schools deter some teachers who wish to express their opinion recoil, especially if their views differ from the traditional or prevailing opinion of the head teacher.

The study further sought to find out how head teachers perceive and implement distributed leadership in their schools. The two sub-themes that emerged from the interview responses are reactions and changes in terms of leadership style.

During the interview nine (9) out of the ten (10) head-teachers admitted that different leadership style adopted by school head teachers influence how they distribute leadership. It was evident across the two countries that although all the head teachers use distributed leadership, they agreed that they use other leadership style such as situational and transformational alongside distributed leadership styles. This combination according to the head teachers makes it difficult to strictly follow the principles of distributed leadership. Some of the following comments were made:

Male Head Teacher, UK1 (MHT UK1) narrated:

“It’s quite difficult because, when at times you are overshadowed by your domineering leadership style while trying to adopt distributed leadership style. This is simple, I am a transformational leader.”

In Ghana, a female head teachers (FMHT GH2) emphasized by saying:

“To be honest with you, as a situational leader practicing distributed leadership I sometimes get caught in my own web”

Even though there are positive reactions to the practice of distributed leadership, through interview and observation the researchers found adverse reactions in the implementation and practice of the distributed leadership style. These reactions emanated from the dynamics and different personalities on staff, age and academic qualification. According to the majority of head teachers, some teachers are reluctant to take up responsibilities when given the opportunity. Basically, not all teachers are interested to be part of school leadership others are content with their role as a classroom teacher.

Notwithstanding these dynamics the researchers cautioned head teachers not to dump work and tasks on their staff in the name of distributed leadership but need to be tactical in distributing. The implication from this finding is that head teachers need to identify the capabilities of each member of staff before distribution whiles motivating teachers who are reluctant to work.

Admittedly, the results from the interviews and observation provide evidence that distributed leadership has and is gaining roots among school leaders. Initially, the very old fashion or traditional style of leadership that was practiced by head teachers made staff members become afraid and timid to take risk. Head teachers were cautious and afraid of getting it wrong and the consequences associated with it as echoed by male head-teachers from Northampton-UK and Accra-Ghana

I have been the head teacher for the past 13 years, initially I was I bit scared of sharing power because I feared I might been seen by my staff as a failure. After attending some workshops I can confidently distribute work ….............. with the benefits of distributed leadership I hardly practice my old style of leadership MHT2, GH2

The above statement was echoed by another male head-teacher from Northampton;

Well during my 10 years of headship at the primary school I have come to know that most inexperienced head-teachers still adopt the traditional leadership style of more dictatorship and a bit of democracy where decision-making is centralized. But currently almost all head-teacher are trying to distribute power because of it numerous benefit.

In each of the schools observed, there were evidence of distributed leadership across all levels where the head-teachers provided opportunities for teachers to lead. The two head-teachers from the schools observed acknowledged the importance of including teachers who have expertise in every level of school management which also provide opportunities for schools to benefit from the capacities of teachers.

With regards to school improvement, there was however consensus among all the head teachers in the study that one of the significant changes has been the involvement of teachers in most aspects of the administration of the schools which has led to school improvement. They argued that any idea and suggestions relating to the introduction of changes in the school, the opinions of teachers vis-à-vis that of the head teacher are considered through whole school meetings or sectional or department meetings. According to majority of the participants, no decision is taken without the participation of all staffs members and this has brought about a cohesive team with a common vision and goal, working towards school improvement.

All the head-teachers interviewed voiced out that whenever leadership is distributed they become less stressful and are able to manage their time effectively leading to school improvement. They further added that distribution of leadership enable them to plan strategically to develop their schools. This is clearly illustrated in the statement of a female head teacher (Female Head Teacher, GH1):

“Well, this style of leadership is helping because the load of work is not only on the head-teacher; you make people responsible in other areas too, and enable me to plan well in advance.”

Similarly, a study conducted in the UK by MacBeath (2005) confirms the findings of this study as MacBeath reported that head teachers' agreed that distributed leadership style allows them to offload work to other teachers which in turn gives them time to implement decisions. Distributed leadership brings sustainability employing a model that could trigger the need to share responsibilities which improves school. A male head teacher (MHT, UK1) echoed:

“Most successful schools have fantastic model of distributive leadership. I think all the evidence point to that, because it means the school is sustainable, it means that its approaches to teaching and learning and school organisation is based on cohesive understanding and shared vision for the school, shared workload, etc. It doesn’t come from just one person but collectively.”

The findings of the study that distributed leadership off load work and improve schools is consistent with Oduro (2004) claims that head teachers are of the view that the distribution of leadership is a way of reducing the pressure of the workload on them. In spite of the views of head teachers on distributed leadership as a way of reducing their workload, it is important to point out that the head teachers were also persuaded that leadership distribution added to effective school leadership because they assumed that teachers were motivated and they were also able to use their expertise

Furthermore, it can be inferred from the interview responses that head teachers in Ghana and UK have embraced the concept of distributed leadership as a tool to improve learning outcomes in schools. From the interviews and observations, it was established that distributed leadership enhanced teacher capacity for building because the confidence level of teachers and leaders of schools are developed and are given the chance to practice leadership that will make them feel that they are part of the whole school development rather than being passive.

From the findings discussed and the literature reviewed, it has been established that majority of the head teachers in Accra and Northampton primary schools in the study are currently practicing distributed leadership. The outcome of distributed leadership relies upon the head teacher who is ready to sacrifice power, and the employees of the organization accepting the opportunity. The researchers therefore argue that it is the duty of the head teacher to make sure that leadership duties are made clear to all since time is an important factor when it comes to distributed leadership. It is also essential that all educational practitioners of all levels adopt distributed leadership in way to develop the growth of the school.

We further opine that head-teacher should give the appropriate roles to teachers who have the knowledge and ability to give out their best. In this context we argue that allowing teachers to engage in unfamiliar work in which they have no expertise may in the end give more work to the leader rather than lessening Similarly, allowing incompetent teachers to participate in managing the school is in a way a risk to the development of the school. We therefore suggest that teachers must demonstrate readiness and willingness to take and accept various leadership roles before they are assigned. This is because it is a necessity to have the ability of trust and responsibility from everyone in the school because if this trust is left to the head-teacher it will not be respected.

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion for effective distributed leadership in schools, head teachers should endeavour to create network and support among teachers and head-teachers. This will be helpful in way to improve and achieve the abilities and talents of teachers and head teachers across schools.

Given the findings, the researchers recommend that head teachers should find ways of giving freedom to teachers who are deemed and ready to lead particular areas of the school even if it is for a shorter time. Additionally, a well-structured programme of high quality in-service training should be developed and offered to every head teacher and teacher in order for every school to develop appropriately.

Finally we argue that it is necessary to provide much specific programmes that are related to leadership skills and knowledge for head-teachers and teachers periodically to keep them abreast to the dynamic nature of distributed leadership.

References

Abu, N.M.S., 2010. Distributed leadership in secondary schools: Possibilities and impediments in Bangladesh. Arts Faculty Journal, 19(32): 19-32.

Bryman, A., 2012. Social research methods. 4th Edn., New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, L., L. Manion and K. Morrison, 2011. Research methods in education. 7th Edn., London: Routledge.

Creswell, J.W., 2012. Educational research. 4th Edn., Boaton, MA: Pearson.

Dampson, D.G., 2015. Teacher participation in decision-making in Ghana basic schools. A study in Cape Coast and Mfantseman Municipality in the Central Region of Ghana. A Thesis Submitted to the University of Northampton for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy.

Danielson, C., 2006. Teacher leadership that strengthens professional practice. New York: Routledge.

Hargreaves, A., A. Boyle and A. Harris, 2014. Uplifting leadership. London: Jossey Bass.

Hargreaves, A., A. Harris, A. Boyle, K. Ghent, J. Goodall, A. Gurn, L. McEwen and J.C. Stone, 2010. Performance beyond expectations. London: National College for Leadership and Specialist School and Academic Trust.

Harris, A., 2002. Effective leadership in schools facing challenging contexts. School Leadership and Management, 22(1): 15-26. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Harris, A., 2004. Distributed leadership and school improvement. Leading or misleading? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 32(1): 11-24. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Harris, A., 2013. Distributed leadership matters. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Jones, M. and A. Harris, 2013. Discipline collaboration: Professional learning with impact. Professional Development Today, 15(4): 13-31. View at Google Scholar

Leithwood, K. and D. Jantzi, 2000. The effects of transformational leadership on organisational conditions and student engagement with school. Journal of Educational Administration, 28(2): 112-129. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Leithwood, K., B. Mascall and T. Stratuss, 2009. Distributed leadership according to the evidence. London: Routledge.

Lizotte, J.O., 2013. A qualitative analysis of distributed leadership and teacher perspective of principal leadership effectiveness. Unpublished Doctor of Education Thesis, Northeastern University, Boston, MA.

MacBeath, J., 2005. Leadership as distributed: A matter of practice. School Leadership and Management, 25(4): 349-366. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Mayrowetz, D., 2008. Making sense of distributed leadership: Exploring the multiple usages of the concept in the field. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3): 424-435.

Oduro, G.K.T., 2004. Distributed leadership in schools: What english headteachers say about the ‘pull’ and ‘push’ factors. Paper Presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of Manchester, 16 – 18 September 2004.

Oduro, G.K.T., 2007. Coping with the challenge of quality basic education: The missing ingredient. In D.E.K. Amenumey, Ed. (2007). Challenges of Education in Ghana in the 21st Century. Accra: Woeli Publishers.

OECD, 2001. Citizens as partners – OECD handbook on information, consultant and public participation in policy-making. OECD. pp: 108.

Spillane, J.P., 2006. Distributed leadership. Jossey-Bass: A Wiley Imprint.

Timperley, H.S., 2005. Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(4): 395-420. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Wadesango, N., 2011. Strategies of teacher participation in decision-making in schools: A case study of Gweru District Secondary Schools in Zimbabwe. Kamla-Raj Journal of Social Sciences, 27(2): 85-94.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher