Comparing Collaborative Writing Activity in EFL Classroom: Face-to-Face Collaborative Writing versus Online Collaborative Writing Using Google Docs

The Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Lampang Rajabhat University, Lampang, Thailand.

Abstract

Collaborative writing is acknowledged as one of the most beneficial writing exercises for improving writing skills. This study aimed to look at the errors of online collaborative writing using Google Docs and face-to-face collaborative writing, as well as to find out how satisfied students were with both modes. Purposive sampling was used to pick 32 Thai second-year English major students (19 females, 13 males) from Writing II. A record form of the error kinds derived from Norrish (1983) a questionnaire, and a semi-structured interview were used as instruments. Frequency and percentage were the statistics used. The data revealed that 346 errors were discovered in online mode, while 389 errors were discovered in face-to-face mode, which was at a higher level. The most common types in the online mode were sentence fragments, while the most common kinds in the face-to-face mode were determiners. Grammars were presented to students in both modes, followed by lexis and mechanics. Furthermore, the findings indicated that the students reported being highly satisfied with online mode using Google Docs (X ̅ = 3.50), followed by face-to-face setting (X ̅ = 3.45). Students also had an overall positive feedback on Google Docs and found it useful in terms of writing anywhere and anytime. Based on the results of this study, students in online co-produced texts better than in face-to-face mode. Time independence and features of Google Docs might be the crucial factors which facilitated the students’ writing in online mode.

Keywords:Collaborative writing, Collaborative writing activity, Face-to-face writing, Online collaborative writing, Google docs, Students’ satisfaction.

Contribution of this paper to the literature

This study contributes to existing literature by looking at the errors of online collaborative writing using Google Docs and face-to-face collaborative writing, as well as to find out how satisfied students were with both modes, in order to minimize the students’ writing errors, guide learners’ struggle to overcome their writing developmental errors in both contexts, and allow the students to use the writing tools technology to help them become better writers.

1. Introduction

English has long been acknowledged as a worldwide language and a means for communicating, exchanging, and transferring knowledge, information, and technology, including between countries (Crystal, 2003). Despite its unofficial status, English has long been regarded as an important component of Thailand's educational system. This is because it has been recognized that English is an important tool for learning new things, communicating with people, and obtaining an education.

Mastering English writing skill is a very difficult task for EFL learners. Most EFL learners tend to commit errors in writing regardless of a long period of English study (Wee, Sim, & Jusoff, 2010). Therefore, an appraisal on writing errors in English is seen as one way of improving the writing skills of learners as a measure of language learning success. The outcome of such an objective is a growing interest in researching written errors. A knowledge of grammatical structures, idioms and vocabulary is important in the composition of writing (Sattayatham & Rattanapinyowong, 2008). In fact, errors are considered as the crucial mark of language development in language learning. It is therefore difficult for EFL learners, in particular, to produce English writing, as the learners need skills in the intended language (Richards & Renandya, 2002). The studies of Phoocharoensil et al. (2016); Sermsook, Liamnimit, and Pochakorn (2017) and Roongsitthichai, Sriboonruang, and Prasongsook (2019) have argued that writing is considered to be the most challenging skill for learners in English as a foreign language (EFL) context due to their limited language skills or linguistic awareness to the content, structure and language needed for composition writing (Weigle, 2002). Nevertheless, learners should not only learn how to write, but also be conscious of their weakness in order to write a successful piece in English.

The study of errors in writing becomes very essential when it comes to the learning of language since it is a study of the language process (Ellis, 2002). The relevance of the identification of second language learners’ or foreign language learner errors is related by Corder (1974) who notes that “error analysis is part of the study of language learning. It gives us an idea of a learner’s language development and may provide us feedback as to how they are learning” (Corder, 1974).

As a result, researchers and educators have devised an English writing teaching style that improves learners' writing skills and allows them to work in groups. It's referred to as "collaborative learning."

It is believed that every learner has individual differences. When learners interact, or collaborate, and brainstorm with a group, a more meaningful and brighter idea will come out (Vygotsky, 1978). Consequently, collaborative activities become recognized as one of the useful tools which can be apparent in writing processes which cannot be fully described by a neat paradigm. This is also asserted by Zamel (1982) who stated that the writing process is an approach to incorporate writing skills which occurs in the recursive nature of the composing process from the time that English language skills start developing.

Reid (2002) also values the collaboration and emphasizes the focus of this approach to process teaching on how the process is related to writing approach tasks by problem-solving method in areas such as audience, purpose, and the situation for writing. Focusing on this approach, Hyland (2003) further emphasizes that writers are independent producers of texts and further addresses the issue of what teachers should do to help learners perform writing tasks.

Apart from collaborative learning, collaborative writing (CW) has received increasing attention in the past decades (Zhang, 2018). According to Dobao (2012) CW is a powerful method that enhances writing skills. Hence, collaborative writing seems to have positive effects on language learners, especially in writing skills. According to McDonough and De Vleeschauwer (2019) it is believed that this activity could explore not only effective writing skill, but also real-world social and professional skills. Thus, CW activities would encourage students to collaborate, negotiate, or interact among them during activities (McDonough, Crawford, & De Vleeschauwer, 2016).

Nevertheless, there is a limitation of collaboration in classrooms. Students may not have much time to read and build on each other’s work; however, in collaborative online environments, they are given this opportunity (Hewitt & Scardamalia, 1998). Having students working together is not restricted to in-class communication. Online collaborative writing improved fluency and grammatical accuracy (Elola, 2010). In online collaboration, students can create, share information, and build consensus as much as they wish. Through online, collaborative written assignments, group discussions, students can enhance knowledge construction (Zhu, 2012).

With the advancement of internet technologies, online collaborative writing (OCW) tools such as Google Docs is a learning tool which helps to implement the learner-centered approach in a collaborative learning environment. According to Oxnevad (2013) document sharing provides students with opportunities to receive immediate feedback. Since Google Docs is stored online, students can work at school and at home from any computer with the internet connection. Therefore, Google Docs provides support for collaboration in real time so students and teachers can have a virtual mini-conference about the work in front of them from any location.

The study's focus has shifted from individual writing to communal knowledge, and from in-class writing to web-based tools for writing beyond the class. Furthermore, it was designed to compare the writing abilities of students as a result of utilizing Google Docs with face-to-face collaborative writing. If Google Docs is successful in improving students' writing skills, it will be a new option for language teachers who are short on time.

In short, the concept of teaching writing was shifting, and teachers were faced with adapting their teaching practices to integrate technologies while redefining writing and learning for the 21st century (Oxnevad, 2013). With the advancement of computer networks, online collaborative learning becomes possible even if students cannot meet in a classroom (Macdonald, 2006). The utilization of the World Wide Web in a writing course can help encourage CW. Many organizations have tried to use technology in collaborative efforts. Apart from blogs, wikis, and chat rooms, Google Docs is an online digital tool that gives teachers some significant tools to assist pupils to develop their writing skills in the twenty-first century.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collaborative Writing

According to Haring-Smith (1994) collaborative writing is defined as involving more than one person who contributes to the creation of text so that “sharing responsibilities” becomes crucial. Similar to Storch (2013) it involves two or more people co-producing a single piece of text. It takes on a variety of forms in an active process including the use of technology as a medium and tool.

Collaborative writing is governed by two major theoretical perspectives (Chapelle & Douglas, 2006) which views the negotiation of meaning and form between learners when they encounter communication difficulties in collaboration with their peers, as leading to learning for the individual learner (Long, 1983). Another theoretical framework, which has been utilized in recent studies and which guides this study, is Vygotsky (1978) sociocultural theory. It claims that the development of higher order mental functions such as logical thinking, problem solving and language learning will first happen during social interaction, between people, before being internalized within the individual, and absorbed to become personal knowledge that can be utilized repeatedly. This perspective supports collaboration as a suitable approach for learning, as learners are provided with opportunities to interact and learn from their partners. Furthermore, Swain (2010) also states that learners who join collaborative activities are able to think at higher levels than they write individually. Different levels of language proficiency, learning styles and background of the students would lead to the collaborative process and improve their ability to solve language problems (Farah, 2011). Furthermore, according to Roberson (2014) peer response is supported by the communicative language teaching approach which puts authentic interactions between the learners as well.

2.2. The Effects of Collaborative Writing in English Writing

Collaboration in writing fosters the syntactic and lexical quality of the text write alone. The researchers compared the texts created by pairs to those created by individuals. Storch found that writing collaboratively produced shorter but better texts in terms of task fulfillment, grammatical accuracy, and complexity, suggesting that CW seemed to fulfill the task more competently. In coincidence with the study of Wigglesworth and Storch (2012) the findings revealed that learners’ reflection on and discussion of language forms, content, and the writing process itself resulted in better knowledge of certain grammatical and lexical forms in collaborative writing. Furthermore, according to Meihami, Meihami, and Varmaghani (2013) the results asserted that a total of fifty Iranian advanced students of English worked on each other’s writing and gave feedback on grammatical points to each other. Obtaining corrective feedback from their peers enabled students to gain their grammatical errors better and improved their grammatical accuracy. Therefore, the results suggested that CW was fruitful in enhancing EFL students to gain in grammatical accuracy produced. Storch (2005) investigated the process and product of CW Twenty-three adult English as a second language (ESL) students taking degree courses at a large Australian institution provided data to the researcher. Students were given the option of writing in groups or independently. Eighteen pupils elected to write in pairs, while five students chose to

2.3. Google Docs

The pandemic of the Coronavirus or Covid-19 has transformed the way people learn and continues to be hybrid learning. Technology has always piqued people's interest, and its implementation has become more prevalent in language teaching and learning. For example, online learning technology is becoming increasingly popular. Many established colleges have begun to provide their courses for free online. It represents a simple and convenient way to get information on practically any topic. Furthermore, online learning appears to be a viable alternative to traditional colleges, particularly for those who lack the time or financial resources to attend live classes Furthermore, according to Lee (2013) the usability of technology in the teaching and practice of writing has also increased. Most classes nowadays, in the digital age, use digital curricula and digital tools. Google Docs is an example of a digital application that is simple and quick to use. The technology is ideal for organizing digital writing workshops that combine peer editing and group collaboration. This collaborative editing tool enables a group of people to work on a document at the same time while viewing the changes made by others in real-time (Chinnery, 2008).

In addition, Google Docs is a web-based word processing tool that offers extra functionalities such as simultaneous editing ability and automated updating (Kessler, Bikowski, & Boggs, 2012). The interface is similar to Microsoft Word. Google Docs can be accessed and edited by multiple users at one time, and it automatically saves the document every six seconds. Students can have a virtual mini-conference about work in front of them from any location. Google Docs also have features of synchronous communication through its chatting application, and it has been reported to be an easy tool to use without requiring much training or technical expertise (Suwantarathip & Wichadee, 2014). Google Docs is another tool that includes the functions of blogs and wikis. Documents can be shared, opened, and edited by multiple users simultaneously and users are able to see character-by-character changes as other collaborators make edits (Woodrich & Fan, 2017). Consequently, these special feature makes Google Docs a powerful application sharing and keeping online documents. Furthermore, students can access their tasks anytime and anywhere (Suwantarathip & Wichadee, 2014).

2.4. Online Collaborative Writing versus Face-to-Face Collaborative Writing

A growing number of studies have been undertaken to examine the impact of teaching writing with the use of technology against F2F writing in the classroom. Many studies contrasted student learning in foreign language classrooms between online technology groups and face-to-face groups, and the results were mixed. Several studies have demonstrated that using online technologies can help students collaborate and improve their learning outcomes (Ansarimoghaddam & Tan, 2013; Neumann & Kopcha, 2019; Suwantarathip & Wichadee, 2014) . In terms of quality, according to Ansarimoghaddam and Tan (2013) the students’ writing quality of F2F and online mode were examined. Thirty Malaysian ESL students worked in groups of three for three weeks to prepare an argumentative essay in both modes. The writing process was divided into three steps by the researchers: planning, drafting, and rewriting, with different groups experiencing each phase in person or online. Students in online collaborative writing created superior prose, according to the findings. Similar to Wichadee (2013) two sections of forty students were asked to work on summarizing five articles over the course of a semester, one section working in F2F mode, and the other working online. Students in F2F mode were asked to complete their tasks in class, while students in online mode could continue their work after class. The findings illustrated that both groups improved their writing skills, but the online groups showed more improvement. Another study of Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) it also compared the outcomes and perspectives of forty university students writing paragraphs in both collaborative mode (F2F and online using Google Docs). The findings were similar to Wichadee (2013) where the Google Docs groups performed better than F2F mode. The researchers suggested that its many capabilities and ease of use as well as its ability to trace every contribution made benefits for learners.

According to the studies cited before, pupils' writing quality improved more in the online method. This could be because students in the online mode were able to continue working after class and manage their schedules. Online collaborative writing evolved over a longer period than face-to-face collaboration. Students may have self-direction, independence, and the opportunity to read and reply on their schedule in an online environment. In contrast to F2F students, they may face time constraints in completing their homework. As a result, grammar and vocabulary may be limited, sometimes as a result of a time constraint in the classroom.

2.5. Writing Errors

Errors are the vital part of effective writing quality and also make it difficult for EFL learners to write in English. Several studies have also been conducted to investigate learners’ written errors. According to Watcharapunyawong and Usaha (2013) this study related the writing errors of Thai EFL students in different types of texts. The paragraphs were written as narratives, descriptions and comparison of different kinds. Errors were classified in 12 groups. In narrative writing, singular/plural form, subject verb agreement, and verb tense were the most frequent common errors, while the most common errors in the description were article, subject-verb agreement, and verb tense, respectively. The comparison errors were verb-tense, singular/plural, preposition and subject verb agreement, respectively. The results revealed that the writing errors were committed due to first language (L1) interference and suggested that in each writing task the mean number of errors tended to be divergent depending on the genre. Similar to Wu and Garza (2014) it examined the forms and features of errors in email in the English language writing of grade six students. The findings revealed that grammatical errors were most commonly observed (subject and verb agreement, sentence fragment, and singular/plural verb). The students made grammatical, lexical, and semantical errors, respectively. The results indicated that in each writing task the mean number of errors tended to be different. The findings mentioned earlier were in line with the studies of errors in English writing of these studies (Alcoy & Biel, 2018; Bennui, 2019; Kongkaew & Cedar, 2018; Moqimipour & Shahrokhi, 2015) the studies also attempted to identify the students’ written errors, the results of these studies were identical.

The studies attempted to identify and categorize the students' writing errors derived from the previous studies. Grammatical errors appeared to be the most common.

2.6. Errors in English Writing in Thai Context

There have also been studies in Thailand concentrating on errors in English writing made by university students during the last decade. Nonkukhetkhong, Sonkoontod, and Wanpen (2013) investigated common errors in English writing of the first-year English major university students at Udon Thani university. The errors made by the pupils were determined to be errors of verbs, nouns, possessive cases, articles, and so on. All of the errors were grammatical. Similar to Watcharapunyawong and Usaha (2013) the study looked at the work of forty second-year English majors in terms of narration, description, and comparison. The findings revealed that there were sixteen different types of mistakes. The most common errors were in the areas of verb tense, word choice, and sentence construction. Another Hinnon (2014) study, this one intended to review the studies of errors in English writing by Thai university students throughout the previous decade. It's safe to presume that faults in grammar and lexis, as well as writing organization, were the three most common types of problems found in Thai university students' English writing. More recently, according to Waelateh, Boonsuk, Ambele, and Jeharsae (2019) fifteen Thai undergraduate students in a university in Southern Thailand participated in the study. Forty-five essays written in English (of different genres) were collected from the students (a total of three essays per student) throughout one semester and analyzed. The researchers identified structures of the student’s essays and compared the errors based on the morphological, lexical, syntactic and discourse categories. The data revealed that the most common errors were syntactic, lexical, morphological, and discourse-related, correspondingly. All of the data from the studies listed above showed that grammatical errors were the most common errors committed by Thai students. It could be because students translated from their first language (interference from the first language) or because they tended to overgeneralize rules when learning new structures. Furthermore, they may be unfamiliar with new rhetorical structures (Khatter, 2019).

In short, error research serves both teachers and students by pointing up areas where better English learning and teaching techniques should be developed in the future. However, the findings of the performed research on errors in collaborative writing, whether in an online setting utilizing Google Docs or in a face-to-face setting, have yet to be fully investigated (Suwantarathip & Wichadee, 2014).

2.7. Learners’ Satisfaction with Computer-Mediated Collaborative Writing (CMCW)

Since learners' attitudes are critical to the effectiveness of collaborative work, learner satisfaction is an important part of the collaborative writing (CW) study. Several investigations that looked into students' opinions, primarily utilizing questionnaires or short interviews, came up with encouraging results.

Participants in Elola (2010) and Strobl (2015) studies were instructed to do solo and CW in pairs. They expressed their appreciation for the CMCW. Additionally, learners can use the synchronous chat tool to discuss, explain, and offer better ideas to their writing. Furthermore, in most research, learners' satisfaction with computer-mediated collaboration was shown to be mainly good in terms of speed and convenience.

Ansarimoghaddam and Tan (2013) used pre-and post-tests to investigate the effects of face-to-face (f2f) and CMCW on learners's writing outcomes. Thirty Malaysian English as a Second Language (ESL) students collaborated in groups of three for three weeks to create an argumentative essay in both face-to-face and online format. The researchers discovered that after participating in CMCW with their peers, the students wrote better essays on their own. In addition, semi-structured interviews with six groups of learners revealed that they prefer CMCW. The learners noted the ability to check back on previous assignments, as well as the flexibility of time and space.

Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) analyzed the outcomes and views of 40 university students composing paragraphs in both modalities of cooperation using Google Docs in another study. Learners gave good feedback in the form of a questionnaire and interviews after completing the exercises. They praised Google Docs for being an easy-to-use collaboration application that boosted their enthusiasm and enabled them to share ideas and collaborate with their colleagues.

3. Methodology

This is a quantitative study with no intervention other than the course syllabus requirement that participants share one writing in an online environment and one writing in a face-to-face setting with the same four-member peer groups throughout the tasks. The current study used CW approaches to give students the option of selecting their members (group of four students). It was because offering students this possibility would increase the collaborative learning environment, which is one of the core ideals of this approach (Mulligan & Garofalo, 2011).

This study was guided by the following research question: What are the variations in error kinds between face-to-face collaborative writing and online collaborative writing with Google Docs?

3.1. Participants

Purposive sampling was used to choose 32 second-year English majors (19 females, 13 males) from a Thai northern institution to participate in argumentative writing. Based on their results in Writing I, a necessary course, they were sorted into three levels: novice (C, D+, and D), intermediate (B and C+), and advanced (A and B+). Heterogeneous groups are made up of students who have a wide range of abilities. There were 17 novices (53.13 per cent), 8 intermediates (25 per cent), and 7 advanced (21.87 per cent) among the participants. All participants took part in both online and face-to-face sessions. The students had no prior experience with collaborative writing, but they did have other sorts of collaborative learning experiences, such as group discussion and dialogue. Students began learning English in primary school and continued through university.

3.2. Collaborative Writing Activities

In all versions, the collaborative writing process followed the same eight steps. The thirty-two students were taught by the same teacher-researcher and went through the same collaborative writing process, which included a midterm and final test as well as instructional and evaluation materials. They did the same brainstorming, freewriting, listing, clustering, sketching, outlining, mind mapping, and other pre-writing tasks. The experiment began in the 12th week when all students participated in face-to-face collaborative writing in class; in the 13th week, they participated in online collaborative writing using Google Docs from their homes. They were given the task of completing an argumentative paragraph in groups of four. The steps of collaborative writing activities in both forms are depicted in the diagram below.

3.2.1. Tasks

At least 100 words were allocated to the arguing paragraph. All of the students (eight groups of four students each) were exposed to all of the modes' steps (F2F in class versus Google Docs in their places). In online mode, only the first and second steps were timed. The students then continued writing at their desks, whereas the F2F groups were expected to complete all of the stages in the class.

Step one: the teacher provided an overview of collaborative and individual writing in both modalities (20 minutes). Writing via Google Docs, an online computer software program was employed in this step.

Step two: listened to an instructor lecture on an argumentative paragraph model and grammatical structure (30 minutes).

Step three: collaborated with their members on outlining, listing, freewriting, brainstorming ideas, and organizing materials (30 minutes).

Step four: created a rough draft (1st draft) by writing an introduction, body, and conclusion (40 minutes).

Step five: revised the original draft, focusing on language, substance, and arrangement, as well as any details that students needed to relocate, add, or eliminate (40 minutes).

Step six: rewrote the manuscript, taking into account the changes made during the revision step (2nd draft) (30 minutes).

Step seven: proofread the second manuscript and correct conventions such as spelling, grammar, punctuation, and mechanics (final draft) (30 minutes).

The last step, published the completed paper (20 minutes).

3.3 Instrument

3.3.1. The Record Form Adapted from Norrish (1983)

The sorts of errors detected in the students' argumentative writing were classified using the record form. Sixteen pieces of their written work (eight from face-to-face and eight from online) were gathered and assessed.

3.3.2. Questionnaire

Using a 5-point scale, the questionnaire was used to assess the students' satisfaction with OCW (Likert Scale). The researcher developed and translated the questionnaire into Thai, which was then validated by three professionals with more than 10 years of experience teaching English writing at the university level. One of them was a native speaker of the language. The alpha coefficient of Cronbach's alpha test yielded a reliability of 0.945. The three experts also offered suggestions for improving the questionnaire. Using mean and standard deviation, the validity of the questionnaire was assessed using the Index of Item Objective Congruence (IOC). The analysis yielded a result of 0.75.

3.3.3. Semi-Structured Interview

The students' qualitative information was gathered through semi-structured interviews. The data was analyzed using content analysis. Six students were chosen at random to participate in the interviews. Each interview was taped in Thai and then translated into English. The translators were evaluated to see if the translated versions were semantically, idiomatically, and conceptually equivalent. Any differences were ironed out, and all specialists agreed. There was one question that went like this: What are your thoughts on utilizing Google Docs for online collaborative writing?

3.4. Data Collection

This study compared the quality of students' argumentative writing in online CW and face-to-face mode. The researcher and two specialists assessed all sixteen pieces of the students' written work. Each error was classified into one of the twenty-five categories adopted from Norrish (1983) scheme of error classification: determiner errors; word choices; verb forms; agreements; prepositions; punctuation; tenses; capitalizations; nouns; misspellings; pronouns; subjects and objects; possessives; sentence fragments; adverbs; conjunctions; repetition of words; adjectives; infinitives and gerunds; miscellaneous unclassifiable errors, space errors; run-on sentences; parallel structures; and overgeneralization.

3.5. Data Analysis

According to the study's objectives, the data analysis technique was divided into two parts.

Stage 1: To determine the frequency and percentage of errors, all of the errors were evaluated and classified according to the types of errors. The errors were then divided into three categories: grammatical, lexical, and mechanical errors. The researcher and two specialists independently verified all of the data (an English lecturer in the English Department and a native speaker).

Stage 2: Using Google Docs and F2F writing, the results from the questionnaire and interview were evaluated and interpreted to determine the level of satisfaction with OCW and F2F writing.

4. Results

The study's findings and comments are given in accordance with the research topic that was proposed before. Using Norrish's error categorization scheme, errors were classified into twenty-five categories (Norrish, 1983). The tables below demonstrate the frequency of errors in both face-to-face and online activities.

4.1. Errors Found in F2F Mode

| Types of Errors | Frequency |

Percentage |

| 1. Determiners | 59 |

15.17 |

| 2 Word choice | 46 |

11.83 |

| 3. Verb forms | 35 |

9.09 |

| 4. Subject-Verb agreements | 28 |

7.19 |

| 5. Prepositions | 27 |

6.94 |

| 6. Punctuation | 23 |

5.91 |

| 7. Tenses | 19 |

4.88 |

| 8. Capitalizations | 18 |

4.62 |

| 9. Nouns | 16 |

4.11 |

| 10. Misspellings | 15 |

3.85 |

| 11. Pronouns | 14 |

3.59 |

| 12. Subjects and Objects | 12 |

3.08 |

| 13. Possessives | 10 |

2.57 |

| 14. Incomplete sentences | 10 |

2.57 |

| 15. Adverbs | 9 |

2.31 |

| 16. Conjunctions | 9 |

2.31 |

| 17. Repetition of words | 8 |

2.05 |

| 18. Word orders | 7 |

1.79 |

| 19. Adjectives | 6 |

1.54 |

| 20. Infinitives and gerunds | 5 |

1.28 |

| 21. Miscellaneous unclassifiable errors | 4 |

1.02 |

| 22. Space errors | 3 |

0.77 |

| 23. Run-on sentences | 3 |

0.77 |

| 24. Parallel structures | 2 |

0.51 |

| 25. Overgeneralization | 1 |

0.25 |

| Total | 389 |

100 |

As shown in Table 1, the determiner errors were found to be the most frequent (15.17%); word choices (11.83%); and verb forms (9.09), respectively.

Regarding the determiner errors, they omitted the determiners or inserted it when it was unnecessary.

Wrong choice of words was the second highest number of errors. The main cause of errors might come from misunderstanding the real meaning of the words; for example, students wrote farther for a further.

The third most frequent errors were the use of verb form; for example, “So he have to pay some money.” “My family have happy.”

4.2. Errors Found in Online Mode

As shown in Table 2, incomplete sentences occurred the most frequently (14.73%); misspelling (13%); and wrong choice of word (9.82%), respectively.

Based on the collected results in online mode using Google Docs, incomplete sentences were found to be the most problematic; for example, “She stressed.” (She is stressed.). “Today, technology an important role in our lives.” (Today, technology has an important role in our lives.).

| Types of Errors | Frequency |

Percentage |

| 1. Incomplete sentences | 51 |

14.74 |

| 2. Misspelling | 45 |

13.00 |

| 3. Wrong choice of word | 34 |

9.83 |

| 4. Errors in the use of conjunctions | 27 |

7.80 |

| 5. Parallel structures | 27 |

7.80 |

| 6. Capitalization | 22 |

6.36 |

| 7. Errors in the use of determiners | 17 |

4.91 |

| 8. Run-on sentences | 16 |

4.62 |

| 9. Errors in the use of verb form | 15 |

4.34 |

| 10. Punctuation | 14 |

4.05 |

| 11. Errors in the use of pronouns | 12 |

3.47 |

| 12. Errors in the use of agreements | 11 |

3.18 |

| 13. Errors in the use of Tenses | 10 |

2.89 |

| 14. Errors in the use of Nouns | 8 |

2.31 |

| 15. Errors in the use of subjects and objects | 8 |

2.31 |

| 16. Errors in the use of adverbs | 7 |

2.02 |

| 17. Errors in the use of possessives | 6 |

1.73 |

| 18. Word order | 5 |

1.45 |

| 19. Errors in the use of adjectives | 4 |

1.16 |

| 20. Errors in the use of infinitives and gerunds | 3 |

0.87 |

| 21. Errors in the use of prepositions | 2 |

0.58 |

| 22. Repetition of words | 2 |

0.58 |

| 23. Space errors | 0 |

0 |

| 24. Overgeneralization | 0 |

0 |

| 25. Miscellaneous unclassifiable errors | 0 |

0 |

| Total | 346 |

100 |

Misspelling was the second frequent error. The majority of the spelling errors committed by the students were occurred by using an incorrect letter, or adding a letter when unnecessary; for example, “My writting is bad.” (My writing is bad.); “…throught the computer screen.” (…through the computer screen).

The third frequent errors were word choices; for example, “It was in 2003 in which that company started.” The subordinate conjunction that is used to denote a time period is when, not in which. So, the correct sentence is: It was in 2003 when that company started.

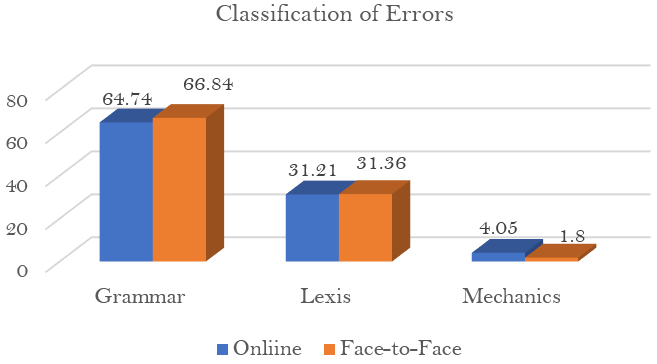

4.3. The Classification of Errors

Figure 1 shows how errors are classified in each manner. They were divided into three groups: grammatical, lexical, and mechanical faults, as shown below:

Figure-1. Percentage of error classification in online collaborative writing and face-to-face collaborative writing.

4.4. The Students’ Satisfaction

Table-3. Students’ satisfaction with online collaborative writing using Google Docs and Face-to-Face collaborative Writing. |

| Writing Activity | SD |

Meaning | |

| Online Collaborative Writing Activity Using Google Docs | 3.50 |

0.51 |

High |

| Face-to-Face Collaborative Writing Activity | 3.45 |

0.58 |

High |

Table 3 shows that the students' satisfaction with OCW utilizing Google Docs was higher (![]() = 3.50), indicating that they were pleased with this activity, followed by the face-to-face collaborative writing activity (

= 3.50), indicating that they were pleased with this activity, followed by the face-to-face collaborative writing activity (![]() = 3.45).

= 3.45).

| Students’ Satisfaction with OCW using Google Docs | Meaning | |

| 1. I am satisfied with the ease of online collaborative writing in creating and edit documents from anywhere. | 3.48 |

High |

| 2. I am satisfied with the ease of access on all devices | 3.52 |

High |

| 3. I am satisfied with tracking the changes in real-time | 3.42 |

High |

| 4. I am satisfied with its auto-saving and automatically stored in Google Drive. | 3.52 |

High |

| 5. I am satisfied with Google Docs’ feature which can be shared with anyone. | 3.58 |

High |

| Total | 3.50 |

High |

Table 4 shows that the students' satisfaction with OCW utilizing Google Docs was high ( = 3.50). Number 5 (I am satisfied with Google Docs' feature that may be shared with anyone) had the highest average of the data, at 3.58, suggesting that the students strongly agree. They were pleased with Google Docs' capability of being able to share documents with anyone. With an average of 3.52, the second average was number 2 (I am satisfied with the ease of access across all devices) and number 4 (I am content with its auto-saving and automated storage in Google Drive). With an average of 3.48, the third average was ranked first (I am satisfied with the ease of online collaborative writing in creating and editing documents from anywhere.). With an average of 3.42, number 3 (I am satisfied with watching developments in real-time) had the lowest average.

Six students were also chosen at random to extract more details in OCW using Google Docs. Six semi-structured interviews were conducted. The students responded to the question in Thai during the interview sessions, and their comments were translated into English. Student 1 (S1), Student 2 (S2), Student 3 (S3), Student 4 (S4), Student 5 (S5), and Student 6 (S6) were the students' names (S6). The excerpts from the six semi-structured interviews are presented here.

S1: I found that this writing activity was useful. Google Docs allows for real-time collaboration, a history of changes, the ability to track changes, auto saving, work from anywhere, offline work mode, exporting, file storage and more. Most importantly, it allowed us to stay organized and instantly see the most recent version of our content.

S2: It was a good activity. I tried to make my paper better by using applications or programs which were very useful. I learned a lot from them, but it took time. Nevertheless, I did not have to feel shy when I needed to share any ideas because there were no f2f activities or interactions among the group members.

S3: I thought it was a good activity. It was similar to a writing exam. I felt quite nervous to have my paper done via online because I needed not only to write the paper but also learned to use Google Docs. I learned that I needed to learn a lot about how to use Google Docs for online writing.

S4: It was quite good to write online because it allowed us to stay organized and instantly saw the most recent version of our content. Nevertheless, I had a problem using Google Docs sometimes as it was quite a new thing for me. For me, it was good because I could stay at my place without attending the classroom. It was good.

S5: I thought it was useful for me because it helped me to save time to attend class. I could write papers anywhere. Sometimes, we used an application or program to collaboratively recheck or revise the writing. It helped us to correct some errors.

S6: I thought this activity was good. With Google Docs, I wrote, edited, and collaborated wherever I was. Everyone in my group worked together at the same time. It saved time to write our assignments. Furthermore, I even used revision history to see old versions of the same document.

Regarding the interview sessions, the results showed some interesting points. It was obvious that the students were satisfied with these OCW using Google Docs. They reported that the benefits of OCW using Google Docs were time saving, conveniences in grammatical error checking, anxiety decreasing, and writing from anywhere.

5. Discussion

When comparing the errors made by the learner in both formats, it is reasonable to infer that grammatical errors are the most common. It was related to Wu and Garza (2014) study, which looked at the types and characteristics of errors in grade six students' English language writing. The statistics also found that the most common errors were grammatical errors. Furthermore, in online collaborative writing, errors were found to be lesser than the errors in F2F mode. Similar to the findings of Ansarimoghaddam and Tan (2013) the students’ writing quality of F2F and online mode were examined. The findings suggested that students in online collaborative writing produced text better. Ansarimoghaddam and Tan (2013); Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) and Neumann and Kopcha (2019) also confirmed that the use of online collaborative technology facilitated better writing outcomes.

The students appeared to be confused with English grammar, based on the factors of their writing errors. In terms of grammar mistakes, they may only have a few opportunities to practice English writing, which is difficult for Thai students. They are required to memorize a variety of grammatical rules. Furthermore, when it comes to lexical errors, students may lack the necessary language to describe their views. They did, however, try to convey what they were thinking by substituting common words for the unfamiliar ones. These errors could be due to a lack of vocabulary. Students appeared to struggle with spelling words with similar letter sounds. Students were also confronted with mechanical issues in addition to spelling issues. This could be owing to a lack of knowledge with mechanics such as punctuation, which are not employed in Thai but are crucial in English.

In terms of independence in an online environment, students did not feel compelled to write a paragraph at their desks. They may feel relaxed when offering their ideas online, but they may feel stressed and hesitant when participating, engaging, or sharing ideas in a face-to-face setting to address any flaws made during F2F activities. Furthermore, they used Google Docs for online collaborative writing because they used a personal computer that included Microsoft Word. This tool may make it easier for students to complete their activities by automatically checking for grammar errors. These factors appeared to aid the students' OCW writing quality.

Students' satisfaction with OCW using Google Docs was high, and it was related to generating and editing documents, simultaneously working with team members, utilizing on all devices, tracking changes, auto-saving, and sharing and communicating with team members. Furthermore, real-time collaboration, auto-saving, working from anywhere, reducing nervousness while interacting with peers, and the good feature of correcting grammatical faults are all advantages of OCW using Google Docs for interview sessions. The results are consistent with the previous study of Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) that the satisfaction of another group of university students towards collaboration in writing using Google Docs are also positive. They rated Google Docs highly as an ease of access and a good collaborative tool that increased their motivation and encouraged them to share ideas and interact with their peers. However, the findings were not generalizable to other contexts as the present study was limited to only thirty-two university students in a northern Thai province.

In short, the present study suggested that OCW seemed to foster the students’ writing skills. However, the findings were not generalizable to other contexts as the present study was limited to only thirty-two university students in a northern Thai province.

6. Conclusion

The current study compared written errors made by Thai EFL students when producing argumentative writing in both online and face-to-face settings. According to the data, students produced various types of errors in various modes of writing. Determiners, word choices, and verb forms were found to be the three most common errors made by students in F2F mode, with overgeneralization being the least common. The research revealed that sentence fragments, misspellings, and word selections were the three most common errors in online mode utilizing Google Docs.

Based on the findings of Thai undergraduate students from a Thai institution in northern Thailand who wrote in an online environment versus in a face-to-face environment, it was clear that the outcomes of writing quality in OCW using Google Docs were better than the results in F2F mode.

Regarding the error classifications, they were classified into three categories: grammatical, lexical, and mechanical errors. The findings of the present study were confirmed by Hinnon (2014) that the most errors made by two modes of students were the errors of grammar. Furthermore, the findings of Waelateh et al. (2019) confirmed the results of the present study that the errors were based on the lexical and syntactic.

Furthermore, the students expressed high levels of satisfaction with Google Docs. Students cited real-time collaboration, auto-saving, working from any place, reducing nervousness while interacting with peers, and the good feature of correcting grammatical faults as benefits of OCW utilizing Google Docs.

7. Suggestions for Future Studies

Future research studies could examine the impact of CW on students' writing motivation using F2F and Google Docs techniques. If students are happy with their technology-based learning, assigning them to collaborate outside of class can help teachers save time and facilitate students' writing. In addition, when different educational tools are used to compare with Google Docs, students' critical thinking skills may be tested. When technology is used more in language classrooms, students can obtain a lot of benefits from blended learning.

References

Alcoy, J. C. O., & Biel, L. A. (2018). Error analysis in written narratives by thai university students of elementary Spanish as foreign language. Ogigia. Electronic Journal of Hispanic Studies, 24, 19-42.Available at: https://doi.org/10.24197/ogigia.24.2018.19-42.

Ansarimoghaddam, S., & Tan, B. H. (2013). Co-constructing an essay: Collaborative writing in class and on wiki. 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature®, 19(1), 35–50.

Bennui, P. (2019). Lexical borrowing in English language tourism magazines in Southern Thailand: Linguistic features of Thai English words and users’ perspectives. Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Office, 3(19), 452-502.

Chapelle, A., & Douglas, D. (2006). Assessing language through computer technology (Vol. 138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chinnery, G. (2008). You've got some GALL: Google-assisted language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 12(1), 3-11.

Corder, S. P. (1974). Error analysis. In J.P.B. Allen and S.P. Corder (Eds.), Techniques in applied linguistics (The Edinburgh Course in Applied Linguistics: 3). (Language and Language Learning) (pp. 122-154). London: Oxford University Press.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dobao, A. F. (2012). Collaborative writing tasks in the L2 classroom: Comparing group, pair, and individual work. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21(1), 40-58.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2011.12.002.

Ellis, R. (2002). Second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elola, I. (2010). Collaborative writing: Fostering foreign language and writing conventions development. Language Learning & Technology, 14(3), 51-71.

Farah, M. (2011). Attitudes towards collaborative writing among English majors in Hebron university. Arab World English Journal, 2(4), 136-170.Available at: https://doi.org/10.29252/ijree.2.4.51.

Haring-Smith, T. (1994). Writing together: Collaborative learning in the writing classroom. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

Hewitt, J., & Scardamalia, M. (1998). Design principles for distributed knowledge building processes. Educational Psychology Review, 10(1), 75-96.

Hinnon, A. (2014). Common errors in English writing and suggested solutions of Thai university students. Humanities and Social Sciences, 31(2), 165-180.

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kessler, G., Bikowski, D., & Boggs, J. (2012). Collaborative writing among second language learners in academic web-based projects. Language Learning and Technology, 16(1), 91–109.

Khatter, S. (2019). An analysis of the most common essay writing errors among EFL Saudi female learners (Majmaah University). Arab World English Journal, 10(3), 364-381.Available at: https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol10no3.26.

Kongkaew, S., & Cedar, P. (2018). An analysis of errors in online English writing made by Thai EFL authors. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 7(6), 86-96.Available at: https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.6p.86.

Lee, J. (2013). The role of technology in teaching and researching writing. Contemporary Computer-Assisted Language Learning (pp. 287–302). London: Bloomsbury.

Long, M. H. (1983). Native speaker/non-native speaker conversation and the negotiation of comprehensible input1. Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 126-141.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/4.2.126.

Macdonald, J. (2006). Blended learning and online tutoring: A good practice guide. Aldershot: Gower.

McDonough, K., Crawford, B., & De Vleeschauwer, J. (2016). Thai EFL learners’ interaction during collaborative writing tasks and its relationship to text quality. In M. Sato, & S. Ballinger (Eds.), Peer Interaction and Second Language Learning: Pedagogical Potential and Research Agenda (pp. 185-208). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

McDonough, K., & De Vleeschauwer, J. (2019). Comparing the effect of collaborative and individual prewriting on EFL learners’ writing development. Journal of Second Language Writing, 44(18), 123-130.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.04.003.

Meihami, H., Meihami, B., & Varmaghani, Z. (2013). The effect of collaborative writing on EFL students’ grammatical accuracy. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 52(11), 47-56.Available at: https://doi.org/10.18052/www.scipress.com/ilshs.11.47 .

Moqimipour, K., & Shahrokhi, M. (2015). The impact of text genre on Iranian intermediate EFL students' writing errors: An error analysis perspective. International Education Studies, 8(3), 122-137.Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n3p122.

Mulligan, C., & Garofalo, R. (2011). A collaborative writing approach: Methodology and student assessment. The Language Teacher, 35(3), 5-10.Available at: https://doi.org/10.37546/jalttlt35.3-1.

Neumann, K. L., & Kopcha, T. J. (2019). Using Google Docs for peer-then-teacher review on middle school students’ writing. Computers and Composition, 54(1), 102524.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2019.102524.

Nonkukhetkhong, K., Sonkoontod, K., & Wanpen, S. (2013). Technical vocabulary proficiency and vocabulary learning strategies of engineering students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 88(38), 312-320.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.511.

Norrish, J. (1983). Language learners and their errors. London: Macmillan Press.

Oxnevad, S. (2013). 6 powerful google docs features to support the collaborative writing process. Retrieved from http://www.teslej.org/wordpress/issues/volume14/ej55/ej55m1/ . [Accessed January 2, 2013].

Phoocharoensil, S., Moore, B., Gampper, C., Geerson, E. B., Chaturongakul, P., Sutharoj, S., & Carlon, W. T. (2016). Grammatical and lexical errors in low-proficiency Thai graduate students’ writing. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 9(1), 11-24.

Reid, J. M. (2002). Teaching ESL writing. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberson, A. P. (2014). Patterns of interaction in peer response: The relationship between pair dynamics and revision outcomes. Dissertation. Georgia Georgia State University.

Roongsitthichai, A., Sriboonruang, D., & Prasongsook, S. (2019). Error analysis in english abstracts written by vaterinary students in Northeast Thailand. Chophayom Journal, 30(3), 21-30.

Sattayatham, A., & Rattanapinyowong, P. (2008). Analysis of errors in paragraph writing in English by first year medical students from the four medical schools at Mahidol University. Silpakorn University International Journal, 8(1), 17-38.

Sermsook, K., Liamnimit, J., & Pochakorn, R. (2017). An analysis of errors in written english sentences: A case study of Thai EFL students. English Language Teaching, 10(3), 101-110.Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n3p101.

Storch, N. (2005). Collaborative writing: Product, process and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14(3), 153-173.Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n3p101.

Storch, N. (2013). Collaborative writing in L2 classrooms. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Strobl, C. (2015). Attitudes towards online feedback on writing: Why students mistrust the learning potential of model. ReCALL, 27(3), 340-357.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0958344015000099.

Suwantarathip, O., & Wichadee, S. (2014). The effects of collaborative writing activity using Google Docs on students’ writing abilities. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 13(2), 148-156.

Swain, M. (2010). Talking-it through: Languaging as a source of learning. In Sociocognitive Perspectives on Language Use and Learning. (Ed.), R. Batstone (pp. 112-130). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind is society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Waelateh, B., Boonsuk, Y., Ambele, E. A., & Jeharsae, F. (2019). An analysis of the written errors of Thai EFL students’ essay writing in English. Songklanakarin Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 25(3), 55-82.

Watcharapunyawong, S., & Usaha, S. (2013). Thai EFL students' writing errors in different text types: The interference of the first language. English Language Teaching, 6(1), 67-78.Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n1p67.

Wee, R., Sim, J., & Jusoff, K. (2010). Verb-form errors in EAP writing. Educational Research and Review, 5(1), 16-23.

Weigle, S. C. (2002). Assessing writing. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wichadee, S. (2013). Improving students’ summary writing ability through collaboration: A comparison between online Wiki group and conventional face-to- face group. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(3), 107-116.

Wigglesworth, G., & Storch, N. (2012). Collaborative writing as a site for L2 learning in face-to-face and online mode. Technology writing context and tasks (pp. 113-130). Texas: CALICO.

Woodrich, M., & Fan, Y. (2017). Google Docs as a tool for collaborative writing in the middle school classroom. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16(1), 391-410.Available at: https://doi.org/10.28945/3870.

Wu, H.-P., & Garza, E. V. (2014). Types and attributes of English writing errors in the EFL context-A study of error analysis. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 5(6), 1256-1262.Available at: https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.6.1256-1262.

Zamel, V. (1982). Writing: The process of discovering meaning. TESOL Quarterly, 16(2), 195-209.Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3586792.

Zhang, M. (2018). Collaborative writing in the EFL classroom: The effects of L1 and L2 use. System, 76(1), 1-12.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.04.009.

Zhu, C. (2012). Student satisfaction, performance, and knowledge construction in online collaborative learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 127-136.

Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |