Peer Scaffolding Behaviors in English as a Foreign Language Writing Classroom

1,2Department of English, School of Liberal Arts, University of Phayao, Thailand.

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the kinds of peer scaffolding behaviors occurring during English as a Foreign Language (EFL) writing activities through three steps of writing process. The participants comprised ten English major students in writing classroom in University of Phayao selected by purposive sampling. They were classified into five expert EFL learners and five novice EFL learners according to their scores of the written paragraph they wrote before participating in the study by using writing rubric. The instruments consisted of five lesson plans through writing process and an observation form. The results analyzed by Microgenetic Analysis revealed that questioning ranked first by the total frequency of peer scaffolding all learners used, but they never applied greeting to their writing activities. However, ten learners applied various types of peer scaffolding to pre-writing activity while they hardly utilized peer scaffolding in post-writing activity. Noteworthy that both expert and novice learners were able to be scaffolders for their peers by supplementing each other’s knowledge and skills because they may be expert writers in different areas, consequently they were able to produce written works by themselves.

Keywords:Peer scaffolding, Sociocultural theory, Writing process activities, Expert and novice writers, EFL writing, Microgenetic analysis.

Contribution of this paper to the literature

This study contributes to existing literature by investigating the kinds of peer scaffolding behaviors of the Thai EFL learners during engaged in the pre-writing, while-writing, and post-writing activities. The peer scaffolding behaviors which were investigated include acknowledging, agreeing, disagreeing, elaborating, eliciting, greeting, justifying, questioning, requesting, stating, and suggesting.

1. Introduction

Recently, writing in Thailand is increasingly essential skill which is widely used as a tool to facilitate and present learners’ educational knowledge and occupational opportunities, so Thai universities include many English writing courses in the curriculum for their learners with purposes to develop their writing skill and support them to receive better educational and occupational opportunities (Promsupa, Varasarin, & Brudhiprabha, 2017; Sararit, Chumpavan, & Al-Bataineh, 2020). However, writing has been found to be one of the most difficult skills for English as a foreign language (EFL) learners since they cannot yet master this skill because they have produced ambiguous written communication due to inability to apply English grammar appropriately in their writing. Moreover, Thai education focuses on learners’ ability to memorize rather than understand what they have learned and solve the problem in their writing (Dawilai, Kamyod, & Prasad, 2021; Promsupa et al., 2017; Watcharapunyawong & Usaha, 2013) . Especially for Thai EFL learners, grammatical elements and vocabulary are the first serious writing problems that they have faced (Boonyarattanasoontorn, 2017; Harris, Ansyar, & Radjab, 2014; Hinnon, 2014; Thongchalerm & Jarunthawatchai, 2020) . According to these two difficulties, most of these writers can write only simple sentences by copying the given sentence samples, but they cannot create and transfer their thought into sentences by themselves without teacher’s assistance (Inkaew & Yawiloeng, 2015; Thoung, Phusawisut, & Praphan, 2020). Moreover, EFL writers do not know how to express their feelings and thoughts into words because they lack the ideas about what to write, and when they write. Therefore, these EFL writers do not find it easy to write a paragraph in English without the assistance of teacher or peers of the academic community that they belong to Seensangworn and Chaya (2017). Another obstacle of EFL writing in Thailand is teaching approach. Many EFL teachers in Thailand follow the traditional method concentrating on recitation and imitation; as a result, EFL learners rarely have an opportunity to give opinions and lack of social interactions with their teacher and classmates. In writing classes, EFL teachers tend to emphasize learners’ final written products rather than focus on their processes of writing. In addition, these traditional EFL teachers highlight on mechanics, spelling, punctuation, grammar, sentence structure, and so on, with little attention to development or style. These teaching styles do not provide learners to practice creative writing if they have to face the real writing contexts (Dawilai et al., 2021; Ibnian, 2011; Inkaew & Yawiloeng, 2015) . Due to the use of traditional teaching by EFL teachers, Thai EFL learners still have been assisted insufficiently; consequently, they cannot express their thought, knowledge, understanding, and experience through their writing.

To solve these obstacles of EFL writing, the new approach which can help Thai EFL learners in terms of writing process and enhance the potential of writing skill development should be applied since the traditional approach cannot meet today’s writing class requirement. Using new approach with step by step instruction, process approach of writing enhances the result in helping learners develop their ideas and individualizing learners’ competence. Moreover, applying the steps of process approach such as generating ideas, structuring, drafting, revising, and editing, into writing courses is better enhancing of learners’ independent writing ability than traditional approach since the approach has to a certain degree encouraged learners to write with confidence and to feel committed to their work, so they are not worried about their writing being judged as right or wrong (Faraj, 2015). Currently, many EFL teachers not only become more and more interested in how they can support their learners in EFL writing learning such as using process approach but also apply other useful strategies in EFL writing classrooms. One useful strategy for supporting EFL learners in their learning and using form of writing language is scaffolding. As such, in attempting to use process approach and scaffolding in a writing class, the following theoretical and pedagogical background are reviewed.

2. Literature Review

This study is based on a Sociocultural Theory (SCT) of Vygotsky which directly emphasized the interaction between social context and human cognitive development. In the educational context, SCT is applied to classrooms setting and learning is considered as the product of shared activity through learners’ relationship that leads to collaborative learning (Behroozizad, Nambiar, & Amir, 2014). Learners can construct the knowledge and understanding through sharing problem-solving tasks when they engaged socially in any activities, so novice learners are able to solve problems after receiving guidance from knowledgeable persons. An opportunity to learn with/from others is mentioned as the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Vygotsky (1978) mentioned that the ZPD is a key element in learning process and it is defined as the distance between the actual development level (of the learner) as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. With regard to the concept of the ZPD, social factors as assistance from others or different forms such as modeling and giving feedback are highlighted and involved in the ZPD which are considered a distance or domain of abilities or skills that learners still need to learn before reaching a state of being more capable and self-regulated Simeon, 2014). In brief, learning in the zone of proximal development, learners engage opportunities to learn together with others and to gain supports from more knowledgeable peers, thereby leading them to learn by the self.

The notion of scaffolding, which is linked to the ZPD is widely acceptable term of how guidance supports learning development. In order to elevate learner’s performance to its higher potential level, the maximum amount of teacher assistance is needed initially. Then, the level of assistance decreases gradually while learner becomes capable of doing more independently. Finally, the responsibility for the performance is transferred to learner, and scaffolding is removed. At this point, learners can perform independently at the same high level at which he/she was previously able to perform only with assistance or scaffolds (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). Therefore, scaffolding is generally thought of as assistance provided through interactions between a competent other and a learner. However, in a classroom setting where learners engage in collaborative work, learners are provided with multiple forms of support from not only teachers, but also peers (Shin, Brush, & Glazewski, 2020). In conclusion, scaffolding may not only occur during teacher-learner interactions but also during peer interactions when learners work in small groups or pairs.

Peers scaffolding is a form of collaborative learning which has advantages in a number of ways, especially in terms of providing and receiving explanation that can help learners engage in deeper cognitive processing, such as clarifying thinking, reorganizing information, correcting misconceptions, and developing new understanding (Simeon, 2014). From the interaction process, GE and Land (2004 as cited in Simeon (2014)) also pointed out that the process of co-constructing ideas can also lead to improved learning that can later be internalized and used to solve problems independently. Finally, when learners work together, they may experience cognitive conflicts that prompt them to explain and justify their own positions, recognize uncertainties about beliefs, seek new information to resolve disagreements, and recognize alternative points of view.

Noteworthy, peer scaffolding is indispensable in second language (L2) writing because learners do not acquire an L2 as they did in their first language (L1). They need coaching and explicit instruction in order to appropriate the fundamental skills of L2 (Simeon, 2014). Moreover, these learners need the experience of going through the processes of writing as writers, and the development in learners of the recursive strategies and techniques that writers use when composing are emphasized (Faraj, 2015). Therefore, writing process and scaffolding strategies can be applied in L2 writing in order to assist learners improve their writing ability from their present level to the higher one.

In order to make clear purpose that learners will understand and follow the procedures easily, writing process in this study which is adapted from Faraj (2015) will be organized into three stages. First, pre-writing stage, the activities include brainstorming and outlining. Learners can brainstorm in group to generate ideas and list the vocabulary for their paragraph. Then, learners use the ideas from brainstorming to make an outline for their paragraph. Second, while-writing stage, learners use the outline to write the first draft with peers’ and teacher’s suggestion. Third, post-writing, it includes revising and editing.

According to the previous studies, there are fruitful results regarding the use of peer scaffolding strategies in writing process. Sabet, Tahriri, and Pasand (2013) examined the impact of peer scaffolding through process approach on writing fluency of EFL learners. The results revealed that both competent and less competent writers can produce more words per minute, and the average number of words produced by them was greater than the pre-test, they also wrote more clauses and more T-units. The evidence of peer scaffolding towards writing development also coincided with Ranjbar and Ghonsooly (2017) who applied the concept of ZPD and scaffolding to examine the effects of peer-scaffolding on EFL writing ability and finding out how revising techniques are constructed and expanded when two learners are working in their ZPDs. Ranjbar and Ghonsooly (2017) results showed that both reader and writer actively took part in revising the text with assistance transferring mutually between them at the end of the session. The results also indicated that peer scaffolding could be reciprocal rather than unidirectional. Recently, Bhatti, Asif, Akbar, Ismail, and Najam (2020) examined the impact of peer scaffolding through process approach from 49 EFL learners studying at university. The participants were randomly assigned to two groups, one the control group and the other experimental group. They concluded the general results, after using SPSS 16, that peer scaffolding and process approach can enhance words per minute average words in some basic areas of writing fluency.

According to the context of Thai EFL writing classrooms, the research on scaffolding and writing process was also emphasized in Inkaew and Yawiloeng (2015) that investigated strategies and types of peer scaffolding through writing processes in three learners. The research procedures were conducted underlying three stages of writing process: pre-writing, while-writing, and post-writing by using six instructional plans. After four weeks receiving scaffolding from the peers, learners used peer scaffolding’s strategies during pre- and while- writing stage to support vocabulary brainstorming, vocabulary meaning checking, and idea generation of unfamiliar vocabulary by talking to the self. During post-writing stage, learners engaged in peer scaffolding strategies for checking grammar, asking for help about transitions, and checking understanding if writing processes. That is to say, learners were able to use the vocabulary and the English transitions learned from the peers to apply in their writing appropriately. Importantly, there was an evidence of self-scaffolding occurred during the good competent learner talked to the self in order to write an unfamiliar vocabulary.

Although these previous studies in scaffolding and writing process approach abound, there is a gap which is specifically evident in Thai EFL writing classroom that writing process approach and peer scaffolding are not widespread. For more effective EFL writing classrooms, peer scaffolding can be used especially if there are a great number of learners in the class and only one teacher cannot be responsive to all their needs, the use of peer scaffolding can be a valuable asset for EFL teachers.

2.1. Objective of the Study

The objective of this study is to investigate the kinds of peer scaffolding behaviors occurring during EFL writing activities.

3. Method

To provide in-depth information of individual perspectives for this study, qualitative method is used through participant observation technique (Yin, 2014). According to Yin (2014) this technique can provide two distinctive opportunities for collecting data: the ability to gain access to events or groups that are otherwise inaccessible to a study, and the ability to perceive reality from the viewpoint of someone ‘inside’ a case rather than external to it.

The participants’ scaffolding behaviors during writing activities are the main focus of this observation. In the EFL classroom, the researcher has two roles that are teacher and participant observer. These roles enable the researcher to observe both verbal and non-verbal of EFL learners’ behaviors in the EFL writing classroom. In each stage of writing process in every session, the researcher observes ten EFL learners by using audio and video recordings and an observation form to observe the peer scaffolding behaviors occurring during EFL writing activities for two hours in each session. In addition, playing a role as the participant observer gives the researcher an opportunity to take notes with some significant behaviors which can provide partial supplementary data in the final stage of data analysis.

3.1. Sampling Procedure

The participants of the present study were ten English major students with different levels of English proficiency. For qualitative data, they were selected as case study by purposive sampling for a participant observation. Then they were classified to five expert EFL learners and five novice EFL learners according to their scores of paragraph writing they wrote before participating in the study by using writing rubric. During a 5-week period, these ten participants were observed for peer scaffolding strategies and their written products were analyzed for writing development as the whole class introduced to writing process and scaffolding from peers. In addition, ten students who agreed to participate in this study were asked to sign the consent form before participating the data collection, and to consider ethical issue, participants’ pseudonyms were used in the transcription of data collected from participant observation.

3.2.Research Instruments

The writing activities are conducted continuously over five periods, twenty hours in total. Data were collected from the writing activities that ten EFL learners participate in. The research instruments consist of five lesson plans and an observation from. The steps of research instrument design are presented as follows:

First, five lesson plans. The researchers reviewed the course syllabus and the steps of writing process then develop the lesson plans. There were five lesson plans for different four topics of paragraph writing used in this writing activities according to the course syllabus including opinion paragraph, problem-solution paragraph, cause-effect paragraph, and advantage-disadvantage paragraph. Then, the lesson plans were proposed to the supervisor and the experts in order to assess the appropriate of content.

Second, observation form. The researchers reviewed the steps of designing the observation form then develop the form according to the objective of the research. Then, the form was proposed to the experts in order to assess the relation between the objective and the content of the observation form (Index of Item-Objective Congruence: IOC = 1). Finally, the researcher tried out the lesson plans and the observation form with the other section that has same characteristic in order to assess the appropriate of content and time before using with the participants. However, learners are assigned to use Thai language (L1) while they were doing writing activities in order to make them feel free to participate in composing.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis of this study focused on peer scaffolding behaviors which are defined as any part of a dialogue where ten EFL learners talked about the language they were producing, questioned their language use, or corrected themselves or others in order to solve grammatical and lexical problems by cooperating with each other (Swain & Lapkin, 1998 as cited in Li and Kim (2016)). To analyze peer scaffolding behaviors occurring during EFL writing activities, the functions of language adapted from Li and Kim (2016) were employed. The functions consist of acknowledging, agreeing, disagreeing, elaborating, eliciting, greeting, justifying, questioning, requesting, stating, and suggesting (p. 30).

| Peer Scaffolding Behaviors | Definitions |

| Acknowledging (Ac.) Agreeing (Ag.) Disagreeing (Di.) Elaborating (El.) Eliciting (Eli.) Greeting (Gr.) Justifying (Ju.) Questioning (Qu.) Requesting (Re.) Stating (St.) Suggesting (Su.) |

Recognizing or praising others’ ideas, comments, helpfulness, and capabilities. Expressing agreement with others’ viewpoints. Expressing disagreement with others’ viewpoints. Extending and elaborating on self or others’ ideas about writing. Inviting or eliciting opinions, comments, etc. from group partners. Greeting group members. Defending one’s own ideas/comments by giving reasons. Asking questions that one is not clear about. Making direct requirements or requests. Stating one’s ideas and the ideas groups have discussed earlier; posting writing contents or sharing information. Offering suggestions/recommendations about writing contents, structure, format etc. |

4. Results

The following tables present the frequency of the use of peer scaffolding behaviors by ten EFL learners (expert and novice) who enrolled in EFL writing classroom at a university located in Northern Thailand during each stage of writing process identified through participant observation. The results of qualitative data are illustrated based on the researcher’s observation through audio and video recording and their written products in which how ten EFL learners utilized the different peer scaffolding in their writing tasks.

4.1 Peer Scaffolding Behaviors during Pre-Writing Activity

In pre-writing activity, the activities include brainstorming and outlining. Thai EFL learners were able to brainstorm in group to generate ideas and list the vocabulary. Then, these Thai learners used the ideas from brainstorming to make an outline for their paragraph. The data presented in Table 2 also shows that questioning (110) is the most peer scaffolding used by the Thai EFL learners, followed by suggesting (61) and stating (53) respectively while greeting was not occurred in this stage. Moreover, the Expert 2 was the learner who mostly used peer scaffolding (63) while the Novice 5 was learner who least used peer scaffolding (22).

Table-2. The frequency of peer scaffolding behaviors used by ten EFL learners during EFL pre-writing activity. |

| Peer scaffolding behaviors | ||||||||||||

Ac. |

Ag. |

Di. |

El. |

Eli. |

Gr. |

Ju. |

Qu. |

Re. |

St. |

Su. |

Total |

|

| Expert 1 | 3 |

4 |

- |

7 |

1 |

- |

2 |

12 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

43 |

| Expert 2 | 4 |

5 |

- |

9 |

4 |

- |

4 |

14 |

2 |

9 |

12 |

63 |

| Expert 3 | 1 |

5 |

- |

9 |

2 |

- |

2 |

9 |

- |

4 |

5 |

37 |

| Expert 4 | 1 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

- |

3 |

10 |

2 |

5 |

11 |

45 |

| Expert 5 | 1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

- |

2 |

9 |

- |

5 |

7 |

33 |

| Novice 1 | 1 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

- |

- |

11 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

35 |

| Novice 2 | 4 |

4 |

- |

5 |

3 |

- |

5 |

11 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

44 |

| Novice 3 | 2 |

2 |

- |

4 |

1 |

- |

- |

11 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

27 |

| Novice 4 | - |

3 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

3 |

12 |

- |

7 |

9 |

36 |

| Novice 5 | - |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

11 |

- |

1 |

1 |

22 |

| Total | 17 |

35 |

5 |

52 |

20 |

0 |

23 |

110 |

9 |

53 |

61 |

385 |

Move |

Dialogues | Peer Scaffolding | Examples of Written Products |

1 |

Expert 1: The topic teacher gives us today is how do we use Internet to make our study easier (Stating). How do you think about that (Eliciting)? |

Stating Eliciting |

|

2 |

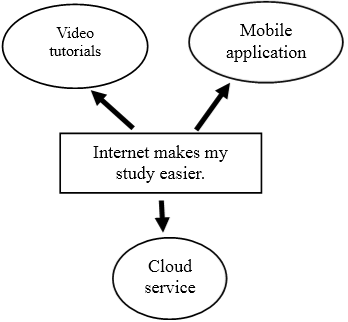

Novice 1: I used to serf tutorial video and use the application to search vocabulary or new knowledge (Stating). | Stating |  |

3 |

Expert 1: Does it look like the benefits of telephone (Questioning)? | Questioning | |

4 |

Novice 1: I mean using Internet to connect the information (Elaborating). | Elaborating | |

5 |

Expert 1: I see. | - | |

6 |

Novice 1: How about you (Eliciting)? | Eliciting | |

7 |

Expert 1: I use Cloud service to store information (Stating). | Stating | |

8 |

Novice 1: It’s cool (Acknowledging). | Acknowledging |

In Table 3, expert and novice writers were planning what they were going to write through brainstorming ideas in group to generate ideas. Begin with stating (move 1), expert posted the topic given by the teacher follows by eliciting (move 1) the Novice 1 to share the ideas. After the Novice 1 stated (move 2) his idea, the Expert 1 asked him questions (move 3) and the Novice elaborated (move 4) on his idea in order to make it clear. Alternating, the Novice elicited (move 6) the Expert to give the idea and then acknowledged (move 8) his partner when he stated (move 7) the cool one. Finally, this pair revealed three ideas for how they used the Internet to make their study easier including video tutorial (move 2), mobile application (move 2), cloud service (move 7) and notes them down on brainstorming worksheet.

Move |

Dialogues | Peer Scaffolding | Examples of Written Products |

1 |

Novice 3: Tell me how to write the topic sentence from these words (Requesting). | Requesting | |

2 |

Expert 3: … Just write it after our ideas and write the topic here when you want to finish the sentence. | - | |

3 |

Novice 3: Like this? | - | Watching movie, listen to music, find a foreigner friend and writing exercise are ways to make my English learning better. |

4 |

Expert 3: That’s not right (Disagreeing) because this is the sentence and all nouns here should be the subject (Justifying). | Disagreeing Justifying | |

5 |

Novice 3: Er…nouns, so I have to add –ing to these words (Elaborating). | Elaborating | Watching movie, listening to music, finding a foreigner friend and writing exercise are ways to make my English learning better. |

6 |

Expert 3: Yes, you can do it (Acknowledging). And then, we have to describe our ideas in the supporting details. | Acknowledging | |

7 |

Novice 3: For watching movies and listening to music, we should listen carefully to find words in order to understand (Stating). | Stating | When we watch movie or listen to music, we should listen carefully to find words. It will make us understand the song. |

8 |

Expert 3: Exactly (Agreeing). Looking without subtitle is another way to practice English (Stating). | Agreeing Stating | We should watch movie with English subtitles. Then, we can watch it without subtitles and … |

9 |

Novice 3: Look at your supporting detail 2, follow can must be V1 –find and speak (Suggesting). | Suggesting | |

10 |

Expert 3: Ah… | We can find new foreigner friends and speaking English with them. |

According to Table 3, the Novice 3 requested (move 1) the Expert 3 to explain her how to write the topic sentence, then she wrote by herself “Watching movie, listen to music, find a foreigner friend and writing exercise are ways to make my English learning better”. When the Expert 3 looked at her sentence, he did not agree (move 4) with it and justified (move 4) the reason. Then the Novice 3 elaborated (move 5) the topic sentence by herself and the Expert 3 encouraged (move 6) her when she could do it. The Novice 3 revised it to “Watching movie, listening to music, finding a foreigner friend and writing exercise are ways to make my English learning better”. However, the Expert 3 agreed (move 8) with the Novice 3 when she stated (move 7) her idea for supporting detail. Noticeably that the Novice 3 could give suggestion (move 9) to expert when she noticed some errors from supporting detail 2 that the Expert 3 wrote “We can find new foreigner friends and speaking English with them”. Finally, the Expert 3 revised it to “We can find new foreigner friends and speak English with them”.

Table-4. The frequency of peer scaffolding behaviors used by ten EFL learners during EFL while-writing activity. |

| Peer scaffolding behaviors | ||||||||||||

Ac. |

Ag. |

Di. |

El. |

Eli. |

Gr. |

Ju. |

Qu. |

Re. |

St. |

Su. |

Total |

|

| Expert 1 | - |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

7 |

| Expert 2 | - |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

5 |

| Expert 3 | - |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

7 |

| Expert 4 | - |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

| Expert 5 | - |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

4 |

| Novice 1 | - |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

| Novice 2 | - |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

1 |

9 |

| Novice 3 | - |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

7 |

| Novice 4 | - |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

1 |

7 |

| Novice 5 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Total | 0 |

3 |

1 |

10 |

6 |

0 |

7 |

13 |

4 |

0 |

11 |

55 |

4.2. Peer Scaffolding Behaviors during While-Writing Activity

During while-writing activity, learners used the outline to write the first draft with peers’ and teacher’s suggestion. Table 4 shows that in this stage questioning (13) was used in the highest level by the Thai EFL learners, followed by suggesting (11) and elaborating (10) respectively while acknowledgment, greeting, and stating were not occurred. In addition, the Novice 2 was the learner who mostly used peer scaffolding (9) while the Novice 5 was the learner who least used peer scaffolding (2).

Move |

Dialogues | Peer Scaffolding | Examples of Written Product |

1 |

Novice 2: Writing the first draft is just writing everything from the outline again, isn’t it (Questioning)? | Questioning | |

2 |

Expert 2: Not really (Disagreeing) because you have to add some words like first, second, third to show their connection (Justifying). | Disagreeing Justifying | |

3 |

Novice 2: OK. | There are three ways … First, I watch … Second, I always … Third, I can … |

According Table 5, the Novice 2 talked about how to write the first draft and asked (move 1) expert that what he understood is true. The Expert 2 told him that was partly true (move 2) and justified (move 2) about signal words, so the Novice 2 added some words in order to show the connection in his paragraph (move 3).

Move |

Dialogues | Peer Scaffolding | Examples of Written product |

1 |

Novice 2: Why you use the word “office device” (Questioning)? | Questioning | |

2 |

Expert 2: I mean electric things that we use at the office. If I use “appliances”, it looks like electric things at you house. (Elaborating). | Elaborating | |

3 |

Novice 2: So, use “an” not “a” here (Suggesting). | Suggesting | |

4 |

Expert 2: Oh, I forget. | Finally, when you do not use a office device … |

According to Table 5, the Expert 2 elaborated (move 2) his idea about the word “office device” he used in the paragraph instead of using “appliances” to his partner after she asked him a question (move 1), then when novice looked at his paragraph closely, she suggested (move 2) him to use the article “an” with “office device”.

4.3. Peer Scaffolding Behaviors during Post-Writing Activity

In the last stage, the post-writing stage included revising and editing. After the Thai EFL learners wrote the first draft, they were required to work in pairs and used a peer review worksheet to review their partner’s paragraph. Then these EFL learners revised and improved their paragraph based on their partner’s review by paying attention to the content and organization of their paragraph. Next, the learners wrote the final draft. Before they published their paragraph, they had to edit their mechanical errors such as capitalization, punctuation, spelling, and grammar changes by using an editing checklist in order to let them focus more on specific points. Obviously, suggesting (12) and questioning (4) were only two kinds of peer scaffolding used by these EFL learners in this stage as revealed in Table 6. However, the Expert 1 and 2 were learners who mostly used peer scaffolding (3 times per each) while the Expert 5 did not use any peer scaffolding in this stage.

Table-6. The frequency of peer scaffolding behaviors used by ten EFL learners during EFL post-writing activity. |

| Peer scaffolding behaviors | ||||||||||||

Ac. |

Ag. |

Di. |

El. |

Eli. |

Gr. |

Ju. |

Qu. |

Re. |

St. |

Su. |

Total |

|

| Expert 1 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

| Expert 2 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

| Expert 3 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

| Expert 4 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

| Expert 5 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

| Novice 1 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

| Novice 2 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

| Novice 3 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

| Novice 4 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

| Novice 5 | - |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

| Total | 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

16 |

Move |

Dialogues | Peer Scaffolding | Examples of Written Product |

1 |

Novice 1: “In order to” here, “i” should be small letter and put full stop here (Suggesting). | Suggesting | |

2 |

Expert 1: Er… How do you know that (Questioning)? | Questioning | In conclusion, … use the smart phone as favor, In order to ... |

3 |

Novice 1: I see in the book here ha ha ha. |

According to Table 7, when the Novice 1 looked at her partner’s final draft, she suggested (move 1) her partner to revise her concluding sentence. However, the Expert 1 questioned (move 2) for novice’s suggestion, she corrected the sentence to “In conclusion, we should use the smart phone as favor in order to enhance the skills”.

In conclusion, these significant results show that the EFL learners applied various types of peer scaffolding behaviors to pre-writing activity while they hardly utilized peer scaffolding in post-writing activity. Noteworthy that the Thai EFL learners both expert and novice were able to be scaffolders for their peers by supplementing each other’s knowledge and skills because they may be expert writers in different areas. That is to say, peer scaffolding may help learners to complete tasks by providing more practical and beneficial instructions to learners in all levels of English proficiency.

5. Discussion

5.1. Learning to Write through Writing Process Activities: From Group Work to Individual Work

Finding of this study reveals that peer scaffolding emerged during the Thai EFL learners engaged in writing process activities participated in group work, pair work, and then individual work. In pre-writing activity, the learners brainstormed in group to generate ideas and list the vocabulary for their paragraphs, then the learners completed an outline worksheet to show the organization of the paragraph. When they were working in group, they had opportunity to talk, share, and plan what they were going to write freely. In while-writing activity, learners started to write the first draft individually with the information from the outline worksheet and the suggestion from both peers and teacher. Finally, post-writing activity, learners read their partner’s paragraph and completed a peer review worksheet in order to give each other feedback on the ideas, organization, and language. Then, learners themselves revised their paragraph again based on their partner’s review. After engaging socially with the activities, learners were able to construct the knowledge and understanding through sharing problem-solving tasks. The solutions to learner’s problems were gained through the involved participants’ or members’ behaviors in a shared context, and the individual development relies on the transmission of experiences from others in the community (Santoso, 2010). As Behroozizad et al. (2014) supported that in the learning process, learner who need help is assisted by expert members or knowledgeable peers, then this guidance is stopped when he or she can act independently, as a result of this guidance, a novice learner gradually becomes the effective member of that community. In brief, engaging in problem-solving activities during writing processes, novice writers are able to solve problems after receiving guidance from expert writers, thereby enhancing these novice writers’ ability to solve problem individually.

5.2. Peer Scaffolding Used by Expert-Novice Writers

According to three stages of writing process, the finding shows that questioning was the rank first by the total frequency of peer scaffolding that ten EFL learners used especially during the pre-writing activity. This may be because questioning is the way the learners asked their partners something when he or she was doubted, unclear, or unsure when they were sharing ideas or something what they were going to write. This is a chance for the EFL learners to elaborate their ideas in order to make their understanding clear as Abdollahzadeh and Behroozizad (2015) supported that the application of questioning in planning stage as observable in the results of observation field note pawed the way for most of learners to express their ideas and to think creatively. It is remarkable that all learners never applied greeting to their writing activities. This may be because it is not necessary to greet group members while they were negotiating in the learning environment. When the learners wanted to draw peers’ attention to some topics, they usually used other gestures such as making eye contact or touching.

5.3. Peer Scaffolding during Pre-writing, While-writing, and Post-writing Activity

It is obvious that ten writers mostly applied various types of peer scaffolding to pre-writing activity especially in brainstorming activity. This may be because brainstorming activity enhanced the EFL learners to consider their writing topic and put in writing any ideas they thought it was promising because many writers would forget their earlier ideas as they brainstormed of new ones. In addition, seeing listed ideas together on paper may aid the learners to make connections and looked at their topics again from a new perspective. Ideas, words list, sort of writing, audience, and purpose for their writing were developed from diagrams or listing ideas made by the learners when they were brainstorming (Faraj, 2015). This result agreed with a previous study (Voon, 2010) that, brainstorming is the prewriting activity that assists participants in generation of ideas for the content of their writing, which enables them to write more developed pieces. In while-writing activity, ten writers applied peer scaffolding to create first draft. As an individual work, the learners themselves composed all information from the outline worksheet into a paragraph so they employed peer scaffolding just for checking grammar and vocabulary. This finding is similar to Inkaew (2015) who revealed that the Thai EFL learners used peer scaffolding strategies during while-writing stage to support vocabulary brainstorming, vocabulary checking, and idea generation of unfamiliar vocabulary. In this present study, however, the EFL learners rarely employed peer scaffolding in post-writing activity to write final draft. One possible reason why the used of peer scaffolding was decreased obviously, this may be because the EFL learners were not aware of the errors or did not know how to correct them, so they had no ideas to write on the peer review worksheet, and they just copied from the first draft to final draft.

Interestingly, the Thai EFL learners were able to be scaffolders for their peers by supplementing each other’s knowledge and writing skills. This is because the learners can be expert writers in different EFL writing contexts. During the learning process, more capable peers (expert writers) are not the only sources of help as Van Lier (1996 as cited in Simeon (2014)) explained that such interactions between learners of similar level of achievement encourage the creation of different kinds of contingencies and discourse management strategies. Moreover, less capable peers (novice writers) are able to help more capable peers in a predictable and sensitive manner within the ZPD. As Li (2009) noted that scaffolding between learners of different proficiency levels can enhance fluency, and the more capable partners become more aware of the status of their own knowledge. This is similar to Sabet et al. (2013) whose research result revealed that both competent and less competent writers in the experimental group have improved in their writing fluency. This is certain that, the role of interaction in peer scaffolding behaviors can improve the level of learners’ writing ability since they can utilize scaffolded assistance while working together and then reach a level of performance beyond their level as well.

6. Suggestions

The findings obtained from this study may provide EFL learners clearer views in classroom interaction and peer scaffolding which can assist them to overcome any struggles they may encounter when engage in English writing activities. Furthermore, the findings can also provide EFL teachers clearer views of peer scaffolding roles in the writing classrooms in order to assist EFL leaners when they write English paragraphs. This information may be beneficial for EFL pedagogy because it will provide EFL peer scaffolding strategies in their EFL writing classrooms in order to enhance their learners’ writing development and provide useful EFL writing pedagogy by emphasizing writing process approach and social interactions to promote L2 writing development. However, further study is needed in order to investigate the impact of peer scaffolding behaviors through writing process on other dimensions of writing skills, such as writing accuracy or complexity. In addition, other studies can be conducted to explore the probable impact that peer scaffolding behaviors can be on the development of other language skills such as listening, speaking and reading.

References

Abdollahzadeh, M., & Behroozizad, S. (2015). On the importance of a socio-culturally designed teaching model in an EFL writing classroom. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 4(4), 238-247. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.238.

Behroozizad, S., Nambiar, R., & Amir, Z. (2014). Sociocultural theory as an approach to aid EFL learners. Reading, 14(2), 217-226.

Bhatti, Z. I., Asif, S., Akbar, A., Ismail, N., & Najam, K. (2020). The impact of peer scaffolding through process approach on EFL learners’ academic writing fluency. Epistemology, 7(8), 102-110.

Boonyarattanasoontorn, P. (2017). An investigation of Thai students’ English language writing difficulties and their use of writing strategies. Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(2), 111-118. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26500/jarssh-02-2017-0205.

Dawilai, S., Kamyod, C., & Prasad, R. (2021). Effectiveness comparison of the traditional problem-based learning and the proposed problem-based blended learning in creative writing: A case study in Thailand. Wireless Personal Communications, 118(3), 1853-1867. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-019-06638-x.

Faraj, A. K. A. (2015). Scaffolding EFL students' writing through the writing process approach. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(13), 131-141.

Harris, A., Ansyar, M., & Radjab, D. (2014). An analysis of students’ difficulties in writing recount text at tenth grade of SMA N 1 Sungai Limau. Journal English Language Teaching, 2(1), 55-63.

Hinnon, A. (2014). Common errors in English writing and suggested solutions of Thai university students. Humanities and Social Sciences, 31(2), 165-180.

Ibnian, S. S. K. (2011). Brainstorming and essay writing in EFL class. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 1(3), 263-272. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.1.3.263-272.

Inkaew, S. (2015). Peer scaffolding during writing processes of lower secondary school students in Chaing Rai province. Independent Study, M.A. (English), University of Phayao.

Inkaew, S., & Yawiloeng, R. (2015). Peer scaffolding during writing processes of lower secondary school students in Chiang Rai Province. Paper presented at the The Academic Meeting of Graduate School. University of Phayao.

Li, M., & Kim, D. (2016). One wiki, two groups: Dynamic interactions across ESL collaborative writing tasks. Journal of Second Language Writing, 31, 25-42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.01.002.

Li, D. (2009). Is there a role for tutor in group work: Peer interaction in a Hong Kong EFL classroom. HKBU Paper in Applied Language Studies, 13(1), 12-40.

Promsupa, P., Varasarin, P., & Brudhiprabha, P. (2017). An analysis of grammatical errors in English writing of Thai university students. HDR Journal, 8(1), 93-104.

Ranjbar, N., & Ghonsooly, B. (2017). Peer scaffolding behaviors emerging in revising a written task: A microgenetic analysis. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1150973.pdf.

Sabet, M. K., Tahriri, A., & Pasand, P. G. (2013). The impact of peer scaffolding through process approach on EFL learners’ academic writing fluency. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(10), 1893-1901. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.10.1893-1901.

Santoso, A. (2010). Scaffolding and EFL (English as a Foreign Language) ‘effective writing’ class in Hybrid learning community. Doctoral Dissertation, Ph.D., Queensland University of Technology.

Sararit, J., Chumpavan, S., & Al-Bataineh, A. (2020). Collocation Instruction in English writing classrooms at the University level in Thailand. Rajapark Journal, 14(35), 24-34.

Seensangworn, P., & Chaya, W. (2017). Writing problems and writing strategies of english major and non-English major students in a Thai University. Paper presented at the International Academic Conference.

Shin, S., Brush, T. A., & Glazewski, K. D. (2020). Patterns of peer scaffolding in technology-enhanced inquiry classrooms: Application of social network analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(5), 2321-2350. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09779-0.

Simeon, J. C. (2014). Language learning strategies: An action research study from sociocultural perspective of practices in secondary school English classes in the seychelles. Doctoral Dissertation, Ph.D., Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Thongchalerm, S., & Jarunthawatchai, W. (2020). The impact of genre based instruction on EFL learners’ writing development. International Journal of Instruction, 13(1), 1-16.

Thoung, T., Phusawisut, P., & Praphan, P. (2020). An action research on the integration of process writing and genre-based approach in enhancing narrative writing ability. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, 12(33), 147-158.

Voon, H. F. (2010). The use of brainstorming and roleplaying as a pre-writing strategy. The International Journal of Learning Annual Review, 6(1), 67-78.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watcharapunyawong, S., & Usaha, S. (2013). Thai EFL students' writing errors in different text types: The interference of the first language. English Language Teaching, 6(1), 67-78. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n1p67.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and method (5th ed.). The United State of America: SAGE Publications.

Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |