Becoming University Language Teachers in South Korea: The Application of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and Social Cognitive Career Theory

Woosong Language Institute, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea.

Abstract

Due to the developments of globalisation, the international reputation, the entertainment industry, and Korean pop culture, a large number of language teachers, international schoolteachers, and professional school staff decided to travel to South Korea for career development and enhancement. However, due to a constant shortage of teachers through high turnover, many South Korean schools and universities are facing recruitment issues. The purpose of this study was to investigate two problems. Why do individuals decide to come to South Korea as foreign language university teachers, and how do individuals describe their teaching experiences as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments in South Korea. From the perspective of the Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT), the results indicated that all participants travelled to South Korea for financial and career development goals. Also, all faced negative experiences and discrimination due to their skin colours and nationalities. The researcher hopes the appropriate personnel can take this study as an opportunity to improve and enhance their current workplace and community for a better environment and development.

Keywords:Discrimination, Foreign language teaching, Interpretative phenomenological analysis, Language teaching, School teachers, Social cognitive career theory, South Korea.

Contribution of this paper to the literature: This study outlines the application of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and Social Cognitive Career Theory, and lists the recent studies that employed the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. The study further discusses the nature and orientation of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.

1. Introduction

Teaching away from their home country is one of the best known and most meaningful career developments for many new university graduates, language teachers, and intercultural professionals who want to expand their horizons to an international location (Hardman, 2001![]() ). As evidenced over the last few decades, P12 schools and universities are facing teacher shortages and recruitment difficulties for their foreign language teacher staffing. There are also shortages of native language speakers for their classrooms and students, particularly for some minority languages other than English, Chinese Mandarin, and Spanish (Dos Santos, 2018

). As evidenced over the last few decades, P12 schools and universities are facing teacher shortages and recruitment difficulties for their foreign language teacher staffing. There are also shortages of native language speakers for their classrooms and students, particularly for some minority languages other than English, Chinese Mandarin, and Spanish (Dos Santos, 2018![]() ). Although there are a reasonable number of junior and senior-level language educators in the market, many of these decided to join international schools due to the attractive salaries and compensations (Young, 2018

). Although there are a reasonable number of junior and senior-level language educators in the market, many of these decided to join international schools due to the attractive salaries and compensations (Young, 2018![]() ). As a result, many university foreign language and culture departments need to recruit language instructors and lecturers all-year-round to cover the demand shortage.

). As a result, many university foreign language and culture departments need to recruit language instructors and lecturers all-year-round to cover the demand shortage.

Several factors may influence the career decisions and development of teachers who are providing teaching and learning instruction at overseas schools and universities. Besides the financial consideration, a recent study (Dos Santos... 2019c![]() ) investigated teachers’ career decisions and perspectives at international schools in a remote archipelagic country in the Asian-Pacific region. The research study focused on in-depth interview data from the participants’ lived experience and, personal backgrounds. It is worth noting that their preceding background may influence a teacher’s career decision and development and lived experience prior to engaging in their teaching and learning services (Kim & Seo, 2014

) investigated teachers’ career decisions and perspectives at international schools in a remote archipelagic country in the Asian-Pacific region. The research study focused on in-depth interview data from the participants’ lived experience and, personal backgrounds. It is worth noting that their preceding background may influence a teacher’s career decision and development and lived experience prior to engaging in their teaching and learning services (Kim & Seo, 2014![]() ). Although the participants shared the same nationalities and studied in the same country (i.e. Australia) before joining the Fijian international schools, their previous lived experiences could not be the same. The researcher employed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and rich sharing to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants’ various career decisions and rich sharing. The results indicated that the remote and isolated location, and limited social networking, in the South Pacific region were two of the limitations which led them to leave their teaching positions. However, many teachers advocated that the respectfulness from the parents and students encouraged them to continue their teaching and learning experiences and career developments in Fiji. Therefore, although people with a similar prior lived experience from the same home country of Australia, the career decisions and development of each teacher could be influenced due to their personality (Dos Santos 2019b

). Although the participants shared the same nationalities and studied in the same country (i.e. Australia) before joining the Fijian international schools, their previous lived experiences could not be the same. The researcher employed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and rich sharing to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants’ various career decisions and rich sharing. The results indicated that the remote and isolated location, and limited social networking, in the South Pacific region were two of the limitations which led them to leave their teaching positions. However, many teachers advocated that the respectfulness from the parents and students encouraged them to continue their teaching and learning experiences and career developments in Fiji. Therefore, although people with a similar prior lived experience from the same home country of Australia, the career decisions and development of each teacher could be influenced due to their personality (Dos Santos 2019b![]() ).

).

Besides remote locations and schools facing recruitment challenges, subject matter shortage is another significant issue in the contemporary educational environment (Dzikunu, Asiaman, & Pajibo, 2019![]() ; Fishman, 2015

; Fishman, 2015![]() ; Zakaria & Yunus, 2020

; Zakaria & Yunus, 2020![]() ) . Unlike social sciences and liberal arts subjects, which may have higher populations of potential teachers, the areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education continues to face extreme shortages of qualified teachers, particularly teachers with industrial and professional experience from the workplace and business environment (Reinhold, Holzberger, & Seidel, 2018

) . Unlike social sciences and liberal arts subjects, which may have higher populations of potential teachers, the areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education continues to face extreme shortages of qualified teachers, particularly teachers with industrial and professional experience from the workplace and business environment (Reinhold, Holzberger, & Seidel, 2018![]() ). Second-career teachers might be one of the effective ways to fill the gaps. A recent research study (Dos Santos, 2019a

). Second-career teachers might be one of the effective ways to fill the gaps. A recent research study (Dos Santos, 2019a![]() ) also explored second-career teachers’ career decisions based on the perspective of the SCCT via IPA (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009

) also explored second-career teachers’ career decisions based on the perspective of the SCCT via IPA (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009![]() ). The study (Dos Santos, 2019a

). The study (Dos Santos, 2019a![]() ) investigated the reasons why a health science professional planned to enter a rural school district after completing their qualifying initial teacher’s license programme. In fact, switching their career development path during mid-age is one of the hardest decisions made by many individuals and their families. Also, health science professionals who are working in an urban facility usually have better career advancement opportunities. Therefore, it is significant to seek an understanding of why and how this career-switching decision is made. Based on the in-depth interview data acquired using IPA, the research indicated that stable employment, money, and an understanding of the teaching mission of health science education were key factors. However, more importantly, the results indicated that the backgrounds and personal goals of switching their career development path from urban environments to rural communities were significant. The outcomes of this study provided meaningful information for rural school districts (Zeidler, 2016

) investigated the reasons why a health science professional planned to enter a rural school district after completing their qualifying initial teacher’s license programme. In fact, switching their career development path during mid-age is one of the hardest decisions made by many individuals and their families. Also, health science professionals who are working in an urban facility usually have better career advancement opportunities. Therefore, it is significant to seek an understanding of why and how this career-switching decision is made. Based on the in-depth interview data acquired using IPA, the research indicated that stable employment, money, and an understanding of the teaching mission of health science education were key factors. However, more importantly, the results indicated that the backgrounds and personal goals of switching their career development path from urban environments to rural communities were significant. The outcomes of this study provided meaningful information for rural school districts (Zeidler, 2016![]() ).

).

1.1. Theoretical Framework

Due to the nature of this study (i.e. the career decisions and development of university foreign language teachers), it is essential to locate the appropriate theoretical framework for guidelines and examination. Based on the purpose of this study, the researcher decided to employ the SCCT (Addis & Yigzaw, 2018![]() ; Brown & Lent, 2017

; Brown & Lent, 2017![]() ; Dickinson, Abrams, & Tokar, 2017

; Dickinson, Abrams, & Tokar, 2017![]() ; Dos Santos & Lo, 2018

; Dos Santos & Lo, 2018![]() ; Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994

; Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994![]() ; Tuomainen, 2019

; Tuomainen, 2019![]() ; Weda & Juanda, 2019

; Weda & Juanda, 2019![]() ) . The SCCT was developed based on the directions of Social Cognitive Theory and Social Learning Theory by Bandura (1982

) . The SCCT was developed based on the directions of Social Cognitive Theory and Social Learning Theory by Bandura (1982![]() ); Bandura (1986

); Bandura (1986![]() ); Bandura (1988

); Bandura (1988![]() ); Bandura (1989

); Bandura (1989![]() ); Bandura (1990

); Bandura (1990![]() ); Bandura (1991

); Bandura (1991![]() ); Bandura (1993

); Bandura (1993![]() ); Bandura and Adams (1977

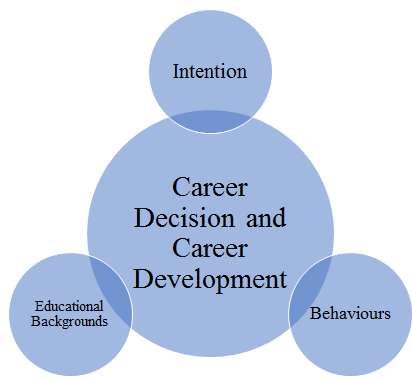

); Bandura and Adams (1977![]() ) one of the most famous psychologists in the United States. The SCCT adapted the ideas and directions from the Social Cognitive Theory by investigating how an individuals’ career decisions and development could be influenced by intention (i.e. personal achievements, goals, purposes, and life directions), internal and external behaviours (i.e. practices, ways of conduct, decisions, steps, exercises), and educational backgrounds (i.e. university degrees, training, student-teaching experience, and research interests). Figure 1 refers to the relationship between the three elements and factors and the career decisions and development of individuals.

) one of the most famous psychologists in the United States. The SCCT adapted the ideas and directions from the Social Cognitive Theory by investigating how an individuals’ career decisions and development could be influenced by intention (i.e. personal achievements, goals, purposes, and life directions), internal and external behaviours (i.e. practices, ways of conduct, decisions, steps, exercises), and educational backgrounds (i.e. university degrees, training, student-teaching experience, and research interests). Figure 1 refers to the relationship between the three elements and factors and the career decisions and development of individuals.

Figure-1. The relationship between the three elements and factors and the career decisions and development of individuals.

Source: Lent et al. (1994![]() ).

).

Previous research Lent and Brown (2008![]() ) indicated that individuals’ career decisions and development could be interconnected and inter-influenced by each element. Also, individuals might be influenced by a single source or multiple sources due to both the internal and external decision-making process and sense-making procedures. In other words, individuals’ career decisions and development could be complicated by various reasons (Dickinson et al., 2017

) indicated that individuals’ career decisions and development could be interconnected and inter-influenced by each element. Also, individuals might be influenced by a single source or multiple sources due to both the internal and external decision-making process and sense-making procedures. In other words, individuals’ career decisions and development could be complicated by various reasons (Dickinson et al., 2017![]() ). As research studies indicated, international schoolteachers from a similar background and educational environment might have different career decisions and development due to their personality, lived experience, and expectations. Therefore, based on the SCCT, each research study would produce individual findings and results with different groups of individuals and teachers based on both internal and external elements and factors (Flores, Robitschek, Celebi, Andersen, & Hoang, 2010

). As research studies indicated, international schoolteachers from a similar background and educational environment might have different career decisions and development due to their personality, lived experience, and expectations. Therefore, based on the SCCT, each research study would produce individual findings and results with different groups of individuals and teachers based on both internal and external elements and factors (Flores, Robitschek, Celebi, Andersen, & Hoang, 2010![]() ).

).

1.2. Purpose of the Study

Based on the literature reviews, the current research study employed the qualitative research method as the structure to investigate two research questions, which were:

- Why do individuals decide to come as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments in South Korea?

- How do individuals describe their teaching experience as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments in South Korea?

There were two reasons why this research study was essential to the current school environment. First, the research study took place in South Korea, a well-known location for overseas teachers and educators to provide educational services and instruction. The researcher attempted to understand and investigate why teachers, particularly university foreign language instructors, decide to come to South Korea. Currently, only a few studies are concerned with this issue. Therefore, it is significant for the researcher, potential teachers coming to South Korea, and school leaders to understand.

Second, unlike China and Japan with rich historical backgrounds and unlimited career opportunities, South Korea is a small region with only one large-sized metropolitan area. Also, many research studies indicate that the suicide rate in South Korea is among the highest internationally. In other words, many South Korean residents and working professionals tend to commit suicide due to workplace bullying, stress, discrimination, and age discrimination from their local and foreign peers in society. Therefore, the researcher attempted to understand and investigate why teachers, particularly university foreign language instructors, decide to come to South Korea for teaching.

2. Methodology

The qualitative research methodology is one of the most common strategies in the field of social sciences, education, political sciences, religious studies, psychology, and even health sciences (Creswell, 2012![]() ). Unlike the quantitative research methodology which relies heavily on statistical reports and analysis, qualitative research methodology mainly focuses on textual data, such as interview transcripts, lived experiences sharing, and field note marking (Creswell, 2007

). Unlike the quantitative research methodology which relies heavily on statistical reports and analysis, qualitative research methodology mainly focuses on textual data, such as interview transcripts, lived experiences sharing, and field note marking (Creswell, 2007![]() ; Merriam, 2009

; Merriam, 2009![]() ). Although qualitative research studies and reports cannot collect large-sized samples internationally, the qualitative research methodology tended to collect rich and in-depth data from a reasonable number of the population, such as sense-making process and lived experiences of a social problem (Smith et al., 2009

). Although qualitative research studies and reports cannot collect large-sized samples internationally, the qualitative research methodology tended to collect rich and in-depth data from a reasonable number of the population, such as sense-making process and lived experiences of a social problem (Smith et al., 2009![]() ). As a result, the researcher decided to employ IPA as the tool to investigate the reasons why individuals decide to come to South Korea as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments.

). As a result, the researcher decided to employ IPA as the tool to investigate the reasons why individuals decide to come to South Korea as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments.

2.1. The Application of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

IPA is one of the newest qualitative research approaches that was developed by Smith et al. (2009![]() ) during the 1990s. Although the method shared many characteristics with phenomenological analysis (Moustakas, 1994

) during the 1990s. Although the method shared many characteristics with phenomenological analysis (Moustakas, 1994![]() ), IPA tends to collect in-depth, vibrant, and intensive data about individuals’ lived experiences, personal approaches, in-depth understanding, and sense-making processes of social issues and phenomena. Jonathan (1996

), IPA tends to collect in-depth, vibrant, and intensive data about individuals’ lived experiences, personal approaches, in-depth understanding, and sense-making processes of social issues and phenomena. Jonathan (1996![]() ) argued that IPA is a type of symbolic interactionism which relies on the understanding, social world, and sense-making processes of individuals. Researchers seek to understand how the individuals describe the meaning of a situation through a process of interpretation. The process may involve how the situation happens, occurs, creates, and makes sense of the individuals, and how the process further impacts the social interactions and behaviours of the individuals. Researchers Jonathan (1996

) argued that IPA is a type of symbolic interactionism which relies on the understanding, social world, and sense-making processes of individuals. Researchers seek to understand how the individuals describe the meaning of a situation through a process of interpretation. The process may involve how the situation happens, occurs, creates, and makes sense of the individuals, and how the process further impacts the social interactions and behaviours of the individuals. Researchers Jonathan (1996![]() ); Smith et al. (2009

); Smith et al. (2009![]() ); Smith and Osborn (2003

); Smith and Osborn (2003![]() ); Tang and Dos Santos (2017

); Tang and Dos Santos (2017![]() ) argued that without the background of the sense-making process, researchers could not understand the motivations and reasons why the individuals conducted and reacted differently to some situations within the community.

) argued that without the background of the sense-making process, researchers could not understand the motivations and reasons why the individuals conducted and reacted differently to some situations within the community.

2.2. Participants

The number of participants is one of the essential elements of IPA. Unlike other qualitative research methods, which may recommend a large number of participants in order to cover the broader population for social issues and problems, IPA tends to focus on a smaller number of participants with in-depth understanding and life experience collections. IPA always focuses on how the individuals explain and describe their inner worlds and sense-making procedures. Therefore, the current research study only invited seven participants. The following table refers to the demography of the participants:

Table-1. Demography of the participants.

| Name | Age |

Nationality and Taught Language | Years of Teaching Experience |

Years in South Korea |

| Amy | 45 |

French, French | 17 |

2 |

| Betty | 47 |

French, French | 20 |

2 |

| Christy | 38 |

Italian, Italian | 10 |

1 |

| David | 56 |

Swiss, German | 30 |

1 |

| Edison | 34 |

Tunisian / British, Arabic | 10 |

2 |

| Felix | 44 |

Turkish, Turkish | 19 |

3 |

| George | 41 |

Japanese, Japanese | 15 |

2 |

2.3. Data Collection

Based on previous studies and the nature of IPA, the researcher decided to employ two sessions of semi-structured interviews with each participant. The first sessions focused on the reasons why individuals decide to come to South Korea as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments. For example, some interview questions addressed their previous personal backgrounds and lived experiences before entering South Korea.

The second interview sessions focused on their current teaching experience and how they describe and make sense of their teaching experience as foreign language teachers at one of the university teaching and learning environments in South Korea. Each interview session lasted between 78 and 156 minutes. All conversations were audio-recorded, transcribed, written, and returned to the participants for member checking procedures.

2.4. Data Analysis

The general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006![]() ) was employed to narrow down the larger-sized transcripts (231 pages) into first-level themes using an open-coding strategy from the perspective of the grounded theory approach. After the open-coding strategy, the first-level themes and subthemes were merged. However, many qualitative researchers advocated that axial-coding strategy should be employed in order to merge into second-level themes and subthemes for reporting. As a result, the researcher needed to narrow down the first-level themes and subthemes with axial-coding strategy. Therefore, two themes and four subthemes were categorised for reporting.

) was employed to narrow down the larger-sized transcripts (231 pages) into first-level themes using an open-coding strategy from the perspective of the grounded theory approach. After the open-coding strategy, the first-level themes and subthemes were merged. However, many qualitative researchers advocated that axial-coding strategy should be employed in order to merge into second-level themes and subthemes for reporting. As a result, the researcher needed to narrow down the first-level themes and subthemes with axial-coding strategy. Therefore, two themes and four subthemes were categorised for reporting.

2.5. Human Subjects Protection

The protection of human subjects was important, particularly given the study’s focus. Therefore, the researcher made every effort to protect their identities, allowing them to remain completely anonymous. The unsigned and signed agreements, personal contacts, audio recordings, written transcripts, completed data, computers, and related documents were all locked in a password-protected cabinet. Only the researcher had the right to access. After the completion of this research study, the related materials were destroyed in order to protect the privacy of the participants.

3. Finding and Discussion

For each interview session, participants were consistently asked the same protocol interview questions with the same content and directions. Based on the theoretical framework, the interview questions tended to focus on the intention (i.e. personal achievements, goals, purposes, and life directions), internal and external behaviours (i.e. practices, ways of conducts, decisions, steps, exercises), and educational backgrounds (i.e. university degrees, training, student-teaching experience, and research interests). The analysis of the interviews yielded two themes and four subthemes, outlined in Table 2.

Table-2. Themes and subthemes.

| Themes and Subthemes | ||

| Coming to South Korea for Career Development and Advancement | ||

| 1.1. | Financial Consideration | |

| 1.2. | Career Advancement | |

2. |

Dislike the Living and Teaching Experience as Foreign Teachers and Professionals | |

| 2.1. | Discrimination based on Skin Colour | |

| 2.2. | Discrimination based on Nationality | |

3.1. Coming to South Korea for Career Development and Advancement

Unlike new university graduates with only a few years of teaching and learning experience, who tended to gain international teaching experience for personal enhancement, participants were mid- and senior-level teachers at university (Hardman, 2001![]() ; Young, 2018

; Young, 2018![]() ). All participants had at least ten years of teaching and learning experience at both P12 and university level before joining this study. Therefore, they were all seeking career development and advancement rather than personal enhancement of life experience. For example, David told the researcher that he came to South Korea for an advancement in position at university level, said,

). All participants had at least ten years of teaching and learning experience at both P12 and university level before joining this study. Therefore, they were all seeking career development and advancement rather than personal enhancement of life experience. For example, David told the researcher that he came to South Korea for an advancement in position at university level, said,

I came to this region because of the university position. I enjoyed my teaching position in Germany and Switzerland before coming to South Korea. I came here absolutely because of the career development, not for fun and not for leisure. (David, German)

3.1.1. Financial Consideration

All seven participants expressed financial consideration as one of their reasons for teaching in South Korea. Based on the SCCT, this element reflected the intention (e.g. financial consideration, goals, and purposes for individuals) (Brown & Lent, 2017![]() ; Lent. et al., 1994

; Lent. et al., 1994![]() ). Unlike many new university graduates and professionals with interests in the cultural perspective of South Korea and East Asian regions, these participants were established language teachers in their home countries or regions. Therefore, the financial consideration was significant as many of them came to South Korea to save money due to lower tax payments. One said:

). Unlike many new university graduates and professionals with interests in the cultural perspective of South Korea and East Asian regions, these participants were established language teachers in their home countries or regions. Therefore, the financial consideration was significant as many of them came to South Korea to save money due to lower tax payments. One said:

South Korea has relatively lower renting fees than many cities and large-size regions in Japan. The renting fees and living expenses in Tokyo and Osaka are pretty high if you compare it to Seoul. But the salary is almost the same. Therefore, coming to South Korea is because of the living expenses and probably the salary. (George, Japanese).

Besides the salary and living expenses, many also expressed that the tax rate is low. Notably, most of the teachers from European countries, believed that the South Korean tax level is much lower than their home countries and regions. One said:

The current tax level in France is very high. Although we may receive pension and retirement fees once we reach the 60s, there is still a long time to go before retirement. Also, it is very hard to save money in Paris. I can save nearly 1,000 Euro each month if I do not spend too much. (Amy, French).

Edison, an Arabic teacher who taught in Europe for nearly ten years before joining the South Korean environment also echoed a similar statement about the retirement and tax. He said:

I spent most of my time in the United Kingdom during the first part of my life. In the United Kingdom, I have to pay a lot of fees, such as Council Tax and Insurance…I cannot see how I can receive benefits from the government…in South Korea, I did not receive any benefits as well as the government in South Korea is even worse, but I paid less…(Edison, Tunisian / British, Arabic).

In short, most of the participants believed that the teaching services in South Korea usually presented good salary, lower tax, reasonable pension plans, and insurance. The participants understood their needs and their purposes based on the intention elements of the SCCT (Lent. et al., 1994![]() ). The previous study also indicated that many international school teachers considered salary and financial sources as their purposes and intentions while selecting jobs and positions internationally (Weiner, 2012

). The previous study also indicated that many international school teachers considered salary and financial sources as their purposes and intentions while selecting jobs and positions internationally (Weiner, 2012![]() ). Although none expressed a positive experience about the insurance and long-term investments for their pension, many stated the renting fees and lower taxes attracted them to the current teaching position in South Korea.

). Although none expressed a positive experience about the insurance and long-term investments for their pension, many stated the renting fees and lower taxes attracted them to the current teaching position in South Korea.

3.1.2. Career Advancement

All participants expressed that they came to South Korea because of career advancement and promotion (Lent. et al., 1994![]() ). SCCT’s element concerning the intention of goals and purposes has been reflected (Bocanegra, Gubi, & Cappaert, 2016

). SCCT’s element concerning the intention of goals and purposes has been reflected (Bocanegra, Gubi, & Cappaert, 2016![]() ; Dos Santos... 2019c

; Dos Santos... 2019c![]() ). All these participants used to hold positions of secondary school teachers and university language instructors in their home countries and regions. However, most of them were university lecturers or assistant professors in their current working environments. Based on the sharing process, they came to South Korea because they tended to gain some upper-level experience before returning. One said:

). All these participants used to hold positions of secondary school teachers and university language instructors in their home countries and regions. However, most of them were university lecturers or assistant professors in their current working environments. Based on the sharing process, they came to South Korea because they tended to gain some upper-level experience before returning. One said:

This country always provided the upper-level title to language instructors. For example, if you are teaching at the university level, they tended to give you the title lecturer or assistant professor…I wanted to gain several years of experience before I returned to Turkey. (Felix, Turkish).

Several similar ideas and sharing experiences were captured during the interview sessions. For example, Betty also expressed her intention of being an assistant professor in South Korea, and said:

I am here just for the title…no other reasons. I don’t like the school and I don’t like the school administrative leaders…I am here for the title. Once I reached the years of experience, I will return and go to another better country (Betty, French).

In short, financial consideration and career advancement were two of the major factors why the participants decided to come to east Asia where they did not have any living or social experiences during the first parts of their lives. In fact, coming to an unfamiliar teaching and learning environment, and living society is a challenging decision and action as most of these participants were not new university graduates or young adults (Gerner, 1990![]() ; Hardman, 2001

; Hardman, 2001![]() ; Skinner, 1998

; Skinner, 1998![]() ) . Specifically, all of them were parents and spouses with family responsibilities. Therefore, most of the sharing tended to focus on financial considerations and career advancement, due to their responsibilities and internal needs (Lent & Brown, 2008

) . Specifically, all of them were parents and spouses with family responsibilities. Therefore, most of the sharing tended to focus on financial considerations and career advancement, due to their responsibilities and internal needs (Lent & Brown, 2008![]() ).

).

3.2. Dislike the Living and Teaching Experience as Foreign Teachers and Professionals

The researcher asked about any additional reasons, for example, student attitudes, administrative styles, student-parent relationships, for them to come and work in South Korea. None of them expressed positive feedback, only referring back to financial and career advancement (i.e. intention) (Brown & Lent, 2017![]() ; Lent. et al., 1994

; Lent. et al., 1994![]() ). During the interview sessions, although many expressed the positive aspects about their position and factors associated with the financial consideration, most of the sharing was negative and unsupportive due to the external environment (Brown & Lent, 2017

). During the interview sessions, although many expressed the positive aspects about their position and factors associated with the financial consideration, most of the sharing was negative and unsupportive due to the external environment (Brown & Lent, 2017![]() ; Lent et al., 1994

; Lent et al., 1994![]() ). Although the written transcripts covered more than 230 pages, more than two-thirds of the sharing was negative. The following three subthemes summarise the negative feedback and aspects of the participants.

). Although the written transcripts covered more than 230 pages, more than two-thirds of the sharing was negative. The following three subthemes summarise the negative feedback and aspects of the participants.

3.2.1. Discrimination based on Skin Colour

Although racism and ethical discrimination is not uncommon in contemporary society, all participants shared nearly one-third of their interview session periods on this issue. Although George is an East Asian (i.e. Japanese) man with similar skin colour, he expressed a lot of discrimination episodes due to his skin colour, and added:

My son, my wife, and I all have a darker skin colour because we all love sports and hiking…But most of the South Korean people believed we are from the rural community…like farmers…basically, they always look down people with dark skin…you cannot imagine how negative that is in South Korea (George, Japanese).

Amy, Betty, and Christy’s ethnicities are African. Their sharing of skin colour was significant and vital. Both shared a lot of negative comments about discrimination, impolite reactions, hate speeches, and even verbal harassment from their experience. For example, Amy said that when she and her family members were having dinner in a restaurant, some restaurants asked them to leave due to their skin colour. She said:

…this is not a single issue, but multiple issues…we went to a lot of restaurants in Seoul, Busan, Daegu, and Jeju before…when we entered the restaurants, the servers never guided us to the table…no water, and no menu…it was very rude…I want to say this is not a single issue…this is the situation in South Korea…(Amy, French)

A similar situation was shared by Christy regarding restaurants and subway metro stations. The following sharing was about the situation in the metro station. She said:

…my daughter and I took the metro during the first week in Seoul. The metro stationmaster asked us to take the bus…they could not speak any foreign languages…but I could hear the words Black, Dark, Dirty, Leave my Country within the conversation…I called the police immediately, but the police arrested us away and asked us do not make any trouble to the Korean residents…(Christy, Italian)

In short, skin colour is one of the significant elements for the negative feedback from all participants (Hardman, 2001![]() ; Odland & Ruzicka, 2009

; Odland & Ruzicka, 2009![]() ). Although many countries and regions have established anti-discrimination laws and policies for protection, the South Korean government and public members did not take any action on the attitudes towards non-South Korean residents. Although South Korea always claims it is one of the wealthiest regions in the East Asian region (Chiu, Zeng, & Cheng, 2016

). Although many countries and regions have established anti-discrimination laws and policies for protection, the South Korean government and public members did not take any action on the attitudes towards non-South Korean residents. Although South Korea always claims it is one of the wealthiest regions in the East Asian region (Chiu, Zeng, & Cheng, 2016![]() ; Lee, Kim, Myung, & Chatfield, 2018

; Lee, Kim, Myung, & Chatfield, 2018![]() ) most of the participants disagreed due to their negative experience. Therefore, South Korean policymakers should pay attention to promote the ideas of equality and globalisation to their residents to increase the overall image of the region.

) most of the participants disagreed due to their negative experience. Therefore, South Korean policymakers should pay attention to promote the ideas of equality and globalisation to their residents to increase the overall image of the region.

3.2.2. Discrimination Based on Nationality

When talking about their sense-making process (Smith & Osborn, 2003![]() ) and positions as university foreign language instructors at the university-level in South Korea, all participants expressed negative explanations about their experience due to their nationality and citizenship. For example, Felix was refused to rent a living unit because of his nationality. He said:

) and positions as university foreign language instructors at the university-level in South Korea, all participants expressed negative explanations about their experience due to their nationality and citizenship. For example, Felix was refused to rent a living unit because of his nationality. He said:

…although I am a university lecturer at a university in Seoul, many of the landlords and owners refused my application because of my nationality or skin colour…the real estate agency also felt negative to help me because I am not Asian or White…I eventually needed to ask the university administrative office to help me up (Felix, Turkish)

Felix’s experience was not an isolated case. All expressed similar experiences during their first few weeks in South Korea, particularly the African participants. Amy shared that one of the real estate agencies asked her to leave the store because of her nationality. She said:

…not just one, many real estate agencies asked how can I get my French citizenship as I look like African…They kept asking how can I gain the French citizenship and even ask me to confirm my citizenship from the government before coming back…ridiculous…(Amy, French)

Christy, as an African Italian, also experienced a similar situation. Once she went to the doctor’s clinic, and the nurses asked her to prove her identification for registration. The nurse asked a lot of impolite questions. She said:

The nurse kept asking me why I am not from Nigeria. I look like African, but should I need to belong to Nigeria or sub-Saharan countries? I grow up in Italy. But those South Korean kept asking me why I am not from Nigeria…this question is illegal in Italy and other European countries. This is harassment. (Christy, Italian)

In short, all participants experienced different levels of discrimination based on their nationality and citizenship. It is worth noting that although there are laws and policies to protect personal information and privacy internationally, many general public members do not understand that some questions are against privacy, particularly questions about citizenship and place of origin. More importantly, many were refused by some services and experienced verbal harassment due to their citizenship. Such negative experiences affected the career decisions and development of language teachers in South Korea which echoed the element of the intention of SCCT (Lent et al., 1994).

4. Conclusion, Limitation, and Implementation

In reflecting on the SCCT, most of the participants advocated that the intention elements influenced their career decisions career development in South Korea. It is worth noting that most of the participants were established language teachers with more than ten years of teaching and learning experience in their home countries and regions. Also, they all brought their family members to South Korea as they would like to have participated in long-term career development and investment in South Korea. However, all expressed significant negative feeling due to the discrimination about skin colour and nationality. Such elements affected their intentions of career development.

The results of this study did not have significant aspects of the educational background and behaviours (e.g. internal) based on the guidelines of the SCCT. Although some research studies indicated that individuals selected their career development and pathways based on their educational background and university degrees, these established teachers with many years of experience were not influenced by this element.

Every study has limitations. The limitation of this study was the background of the participants (i.e. mid- and senior-level language teachers at the university level). Many new university graduates and junior level teachers may have an interest in teaching in South Korea. However, career intentions and ideas may be different from mid-level and senior-level teachers. Therefore, in the future, researchers may extend the research studies for these groups of junior-level teachers.

The results of this study will be beneficial to school administrators, policymakers, human resource professionals, department heads, and government agencies. South Korea always tries to provide language training to its residents and public members in the interests of globalisation. However, there is still significant room for improvement in the areas of discrimination and privacy. As a result, the researcher hopes that the appropriate personnel can take this study as an opportunity to improve and enhance their current workplaces and communities for improved environments and development.

Citation| Luis Miguel Dos Santos (2020). Becoming University Language Teachers in South Korea: The Application of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and Social Cognitive Career Theory. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(3): 250-257. |

References

Addis, K., & Yigzaw, A. (2018). Investigating English teachers perceptions and practices of TBLT in three secondary schools in Awi Zone. Asian Journal of Contemporary Education, 2(2), 90-121.Available at: 10.18488/journal.137.2018.22.90.121.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1990). Some reflections on reflections. Psychological Inquiry, 1(1), 101-105.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0101_26 .

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-l .

Bandura, A. (1988). Organisational applications of social cognitive theory. Australian Journal of Management, 13, 275–302.

Bandura, A. (1989). Perceive self efficacy in the exercise agency: The psychologist. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 10, 411-424.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117-148.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3 .

Bandura, A., & Adams, N. E. (1977). Analysis of self-efficacy theory of behavioral change. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(4), 287–310.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01663995 .

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 .

Bocanegra, J. O., Gubi, A. A., & Cappaert, K. J. (2016). Investigation of social cognitive career theory for minority recruitment in school psychology. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(2), 241–255.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000142 .

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2017). Social cognitive career theory in a diverse world. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 173–180.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716660061 .

Chiu, W., Zeng, S., & Cheng, P. S.-T. (2016). The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(2), 223–234.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2015-0080 .

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dickinson, J., Abrams, M. D., & Tokar, D. M. (2017). An examination of the applicability of social cognitive career theory for African American college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 75–92.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716658648 .

Dos Santos, L. M. (2018). Foreign language learning beyond English: The opportunities of one belt, one read (OBOR) initiative. In N. Islam (Ed.), Silk Road to Belt Road (pp. 175–189). Singapore: Springer.

Dos Santos, L. M., & Lo, H. F. (2018). The development of doctoral degree curriculum in England: Perspectives from professional doctoral degree graduates. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 13(6).Available at: https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2018v13n6a781 .

Dos Santos, L. M. (2019a). Investigating employment and career decision of health sciences teachers in the rural school districts and communities: A social cognitive career approach. International Journal of Education and Practice, 7(3), 294–309.Available at: https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.61.2019.73.294.309 .

Dos Santos, L. M. (2019b). Mid-life career changing to teaching profession: A study of secondary school teachers in a rural community. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(2), 225–227.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1548168 .

Dos Santos, L. M. (2019c). Recruitment and retention of international school teachers in remote archipelagic countries: The Fiji experience. Education Sciences, 9(2), 132.Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020132 .

Dzikunu, C. K., Asiaman, M., & Pajibo, E. (2019). Community participation and educational decentralization in Gbawe cluster of school, Ga South Municipality. Global Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 5(1), 58-71.Available at: 10.20448/807.5.1.58.71.

Fishman, D. (2015). School reform for rural America: Innovate with charters, expand career and technical education. Education Next, 15(3), 8-17.

Flores, L. Y., Robitschek, C., Celebi, E., Andersen, C., & Hoang, U. (2010). Social cognitive influences on Mexican Americans’ career choices across Holland’s themes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(2), 198-210.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.11.002 .

Gerner, M. (1990). Living and working overseas: School psychologists in American international schools. School Psychology Quarterly, 5(1), 21-32.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0090600 .

Hardman, J. (2001). Improving recruitment and retention of quality overseas teachers. In S. Blandford & M. Shaw (Eds.), Managing International Schools (pp. 123–135). London, UK: Routledge Falmer.

Jonathan, A. S. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology and Health, 11(2), 261-271.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400256 .

Kim, M. S., & Seo, Y. S. (2014). Social cognitive predictors of academic interests and goals in South Korean engineering students. Journal of Career Development, 41(6), 526–546.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313519703 .

Lee, D., Kim, Y. S., Myung, E., & Chatfield, H. K. (2018). Integrated casino resort development in South Korea: Perspectives from the government representatives and industry professionals. Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 7(4).Available at: https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0269.1000375 .

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2008). Social cognitive career theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(1), 6–21.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305769 .

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027 .

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Odland, G., & Ruzicka, M. (2009). An investigation into teacher turnover in international schools. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(1), 5-29.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240908100679 .

Reinhold, S., Holzberger, D., & Seidel, T. (2018). Encouraging a career in science: A research review of secondary schools’ effects on students’ STEM orientation. Studies in Science Education, 54(1), 69-103.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2018.1442900 .

Skinner, K. J. (1998). Navigating the legal and ethical world of overseas contracts. The International Schools Journal, 17(2), 60–67.

Smith, J., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Smith, J., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Methods. London, UK: Sage.

Tang, K. H., & Dos Santos, L. M. (2017). A brief discussion and application of interpretative phenomenological analysis in the field of health science and public health. International Journal of Learning and Development, 7(3), 123–132.Available at: https://doi.org/10.5296/ijld.v7i3.11494 .

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analysing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748 .

Tuomainen, S. (2019). Pedagogy or personal qualities? University students’ perceptions of teaching quality. American Journal of Education and Learning, 4(1), 117-134.Available at: 10.20448/804.4.1.117.134.

Weda, S., & Juanda, J. (2019). Anxiety in classroom presentation in teaching-learning interaction in English for students of Indonesian study program at higher education. International Journal of Education and Practice, 7(1), 1-9.Available at: 10.18488/journal.61.2019.71.1.9.

Weiner, L. (2012). The future of our schools: Teachers unions and social justice. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Young, N. A. E. (2018). Departing from the beaten path: International schools in China as a response to discrimination and academic failure in the Chinese educational system. Comparative Education, 54(2), 159–180.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2017.1360566 .

Zakaria, S., & Yunus, M. M. (2020). Flipped classroom in improving ESL primary students tenses learning. International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 9(3), 151-160.Available at: 10.18488/journal.23.2020.93.151.160.

Zeidler, D. L. (2016). STEM education: A deficit framework for the twenty first century? A sociocultural socioscientific response. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11(1), 11-26.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9578-z.

| Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |