Support Services in Social Studies Courses for Students with Hearing Loss

Anadolu University, Education and Research Center for Children with Hearing Loss (ICEM), Turkey

Abstract

Social Studies courses aimed to promote the development of critical thinking skills in students. This study focused on the problems two students with hearing loss encountered while they are using three strategies: “identifying and using reference sources”, “perception of chronology” and “critical reasoning” strategies, which is required for the improvement of the critical skills. Action research method was used. A considerable data were collected through observations, interviews, documents, process products and the research diary. Findings showed that making the content of Social Studies concrete with activities and being a model to students while using strategies fostered the strategies students used. At the end of the study, it was observed that the activities that are supported with rich materials and activities accompanied by active participation contributed to the use of strategies with which at first students faced problems.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Inclusion, Support service.

1. Introduction

The main aim of the Social Studies course is to prepare students for social life. Social Studies courses sought to raise citizens who act democratically within the society and make decisions based on knowledge and logic (Zarrillo, 2012). To realize these aims, students need to improve their critical thinking skills, reflect on the discovery, research and inquiry. As a result, students do not remain within their limits and can attain objective thinking skills enriched with new ideas (Levstik and Barton, 2001).

In this study, the focus is critical thinking skills, which is one of the aims of the Social Studies course. Critical thinking is a way of thinking that enables the association of connections established between events and facts in mind, by combining experiences and knowledge attained (Ennis, 2011). Critical thinking promotes the use of processes that involve classifying, analyzing, summarizing and synthesizing knowledge. Within the critical thinking process, it is essential to recognize and answer the relevant questions, as well as use these questions effectively (Browne and Keeley, 2007). Students with critical thinking skills are able to question the reliability of sources they access rather than just accepting knowledge directly. They can make transfer knowledge more easily and think metacognitively through finding solutions to the problems they face (Bransford et al., 2000).

There are a number of key points that should be considered in the Social Studies course for the improvement of critical thinking skills. Teachers are required to prepare activities that involve using multiple strategies, provide students with adequate time to think about the answers to the questions, ask questions and present activities that require the combination of knowledge and experience, model students in ways of thinking (Zarrillo, 2012). In this way, teachers can create active learning environments that ensure continuous student participation. Active learning is a process that select the strategies they will use to attain knowledge (Gagné and Driscoll, 1988). Many studies emphasize the contribution of critical thinking to educational environments (e.g., (Ikuenobe, 2001; Karabulut, 2012)). Given the benefits of critical thinking, research into critical thinking in the field of education has become more popular in Turkey in recent years (Polat, 2015) but critical thinking among students who need special education like students with hearing loss is little investigated.

In Social Studies classes, as well as the other classes, strategy teaching should be applied to realize critical thinking. Strategy teaching fosters using knowledge and experience, reaching and understanding the knowledge, promoting autonomous learning in students by allowing students to evaluate themselves and changing their opinion when necessary (Jones et al., 1987). Thus, the following strategies are taught in the 4th year of Elementary School: (a) identifying and using reference sources (b) organize information usable forms (c) chronology and perception of space (d) interpret of table, diagram and graph (e) comparison (f) critical reasoning (g) decision-making and (h) use library, online, or other search tools to locate sources (Ministry of Education, 2016). Drawing on the literature, this study focuses on the following three strategies: “identifying and using reference sources,” “perception of chronology,” and “critical reasoning” strategies for the students with hearing loss.

Identifying and using reference sources enables students to reason about a topic using primary resources, such as documents, interviews, letters, diaries, photos and historical artifacts. These resources are essential in overcoming misconceptions that may occur as a result of previous false or deficient knowledge attainment (Bransford et al., 2000). Many researchers emphasized that using more written, audio and visual documents - along with information and communication technologies in Social Studies classes - is essential for understanding the texts within the course content, as well as for the development of critical perspectives (Buchanan, 2015; Alongi et al., 2016). Perception of chronology requires important historical events to be approached in a chronological order and for the concepts of past, present and future to be objectified. As a result, the connection between the present and the past can be observed, along with the similarities and differences between events (Obenchain and Morris, 2011). The topics studied in Social Studies courses are related and have effects on each other. Students make use of their past knowledge and experience when interpreting new experience, and they need to establish critical reasoning to analyze the effects of historical events (Steele, 2008).

Various studies have emphasized that, in Social Studies classes, there is a tendency among teachers to use traditional methods, to teach topics directly, to secure limited student participation, and to allocate insufficient time to discussions (eg. (Hess, 2002; Seyihoglu and Kartal, 2010; Aksid and Sahin, 2011) ). The concepts that are explained through verbal definitions and limited examples thus tend to be memorized without comprehension by students, which leads to a perception of Social Studies being a boring course unrelated to real life (Bailey et al., 2006).

In Social Studies classes, reading, analyzing, and making judgments concerning information are all used simultaneously (Sievers, 2005; Steele, 2008). Because of its role in preparing students for life, concepts and topics within Social Studies classes are related to adult life. Thus, students tend to have difficulties in learning the concepts, most of which they are coming across for the first time (Woolsey et al., 2009). The fact that the time allocated to Social Studies is less than the time allocated to language and mathematics classes, as well as the fact that there is insufficient emphasis on the strategies required for knowledge acquisition, limits students’ critical thinking skills, which are required for metacognitive thinking and solving real life problems (Fitchett and Heafner, 2010; Hawkman et al., 2015)

In addition to the traditional approaches in education, the fact that Social Studies requires the use of complex cognitive skills confines the development of critical thinking skills in students with hearing loss who are enrolled in public schools (Boucher, 2010). Along with these issues, inadequate use of the hearing sense in a child’s critical development period affects the functioning of all sense processes (Bolognini et al., 2012). Restrictions on hearing and language input have a negative effect on the development of creativity, abstract thinking, event sequencing, interpretation, summarizing, understanding alternative perspectives, critical reasoning, and time perception (Mayberry, 2002; Eden, 2008). As a result, the conceptual development of students with hearing loss fails to comply with the conceptual development of students with a hearing ability (Geers et al., 2008; Punch and Hyde, 2010). This problem gives rise to complications in students in terms of critical reasoning between historical or economic events in the past and current events, as well as completing gradual projects (Woolsey et al., 2009). Thus, it is notable that to learn the abstract topics of Social Studies classes, students with hearing loss require a more individualized education than their peers with regular hearing abilities (Shepherd and Acosta-Tello, 2015).

Individualized education practices refer to supporting the special needs students in public schools, in terms of their academic and social orientation inside and outside the classroom, in cooperation with their teachers (Mastropieri and Scruggs, 2010). Education services support, which entered into force with Circular No. 10096465/10.06/5157845 dated May 18, 2015, issued by the General Directorate of Special Education and Guidance Services in Turkey, provides an essential opportunity for the linguistic and academic development of students with hearing loss enrolled in inclusion programs. In support services, which are among the individualized education practices, students who encounter difficulties in solving academic and social problems are tackled through one-to-one practices (Glazzard et al., 2010). It is essential to make effective use of this service, which is provided within a limited time period in the formal education program, for students to address their needs. In Social Studies support service (SSSS) practices, strategy-based interventions should be applied for students with hearing loss and students should be modelled using these strategies (Jones et al., 1987; Akay, 2016). Ensuring that students gain experience using enriched teaching practices and teaching materials, adapted according to their linguistic and academic levels, helps students with hearing loss to understand the topics and concepts. Students who have difficulties in differentiating essential knowledge among the broad content of the school curriculum should be presented with the target topics clearly, with the help of web-based primary resources, visual presentations and associations. Student participation should also be improved (Hicks et al., 2004; Girgin, 2013; Karasu, 2017) . In this study, students with hearing loss were supported regarding their critical thinking skills by identifying and using reference sources, perception of chronology, and critical reasoning strategies. They were also enabled to associate the concepts with real life, confirming times, and determining relations between events.

Inclusion has been widely used in the field of special education. Turkey is among the countries that have adopted these practices. It has been observed that in Turkey, the basic elements of inclusion - including the planning of education - are determined by laws. However, studies on practice show that most necessities have not been addressed. The criticism of inclusion practices in the literature includes the incompetence of school administrators and teachers in supporting students with hearing loss, the negative perceptions of peers with regular hearing abilities, the negative perceptions of parents towards students with hearing loss, and the physical structure of the educational environment (Kayaoglu, 1999; Guleryuz, 2009). Also, there is an ongoing discussion that students with hearing loss enrolled in public schools are not provided with systematic support services inside or outside the classroom, and individualized education programs have not been implemented in the classrooms (Kargin and Baydik, 2002). These problems restrict the active participation of students with hearing loss enrolled in inclusion programs in discussions, as well as teacher-student interaction. Relevant research declares that after the placement of students with hearing loss for inclusion environments, both teachers and students should be supported (Gelzheiser and Meyers, 1991; Donnelly and Watkins, 2011). Also, notably, the number of practical studies on students with hearing loss enrolled in public schools is very limited in the relevant literature (Gurgur, 2008; Akay, 2016). Given this gap, this study sets out to contribute to the previous studies on students with hearing loss in the Social Studies field. Indeed, the findings of the present research are significant and promising in terms of identifying the methods of support for the development of critical thinking skills in students with hearing loss in Social Studies classes, as well as addressing their problems. Students with hearing loss enrolled in inclusion programs, the teachers who support these students, and classroom teachers could benefit from the results of this study.

This study aims to investigate the Social Studies support service practices applied for students with hearing loss enrolled for a public school. In line with this aim, the study sought answers to the following questions: (a) What are the problems that students with hearing loss encounter while learning Social Studies concepts? (b) How were the practices to address these problems carried out?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Model

This study was designed as an action research because the solution for the problems in Social Studies support services was addressed systematically and cyclically (Johnson, 2012). The study was conducted in Anadolu University’s Education and Research Center for Children with Hearing Loss (ICEM). ICEM is a research and intervention center where students with hearing loss are given hearing instruments at an early age and preschool, elementary and middle school students with hearing loss enrolled in public schools are provided with support services using the auditory-oral method.

2.2. Participants

Two elementary school 4th-grade students with hearing loss enrolled in inclusion programs, the researcher as the support teacher, and the classroom teachers took part in this study. Students who participated in the study were given hearing instruments at least 26 months before and were placed in an inclusion environment following parent and preschool education. The students did not have any disabilities other than hearing loss.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Before conducting this research, written permission was obtained from the students’ parents and the classroom teachers. In the permission slips, it was stated that the participants were allowed to leave the study whenever they wanted, and the data would be shared only in scientific platforms (Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2011). A pseudonym was used for each student throughout the study. Based on the honesty and transparency principle, all data were collected through video and audio recordings (Johnson, 2012).

2.4. Procedures

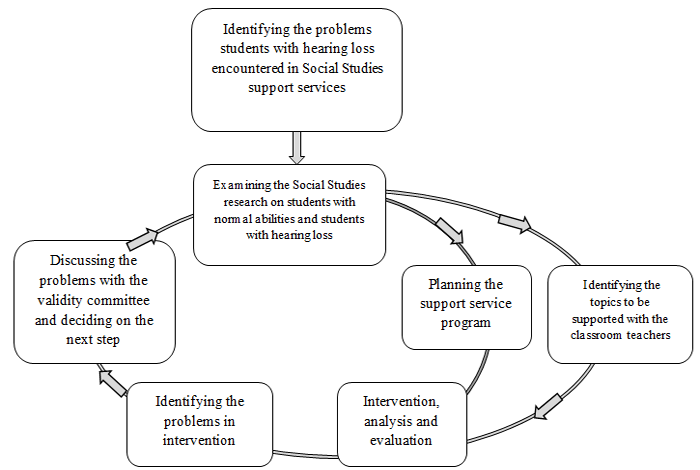

This study focused on identifying the problems encountered by the students with hearing loss within SSSS and developing practices that could address these problems. The weekly schedule of SSSS is presented in Figure 1.

Figure-1. Weekly Schedule of the Social Studies Support Services

Source: This is the cycle of research

Table-1. Social Studies Support Services

| Video Recording No. | Date | Duration | Unit | Subject |

| 1 | 7.10.2016 | 32’51’’ | I Know Myself | Who am I? Our Identity Information and Fingerprints |

| 2 | 11.10.2016 | 35’18’’ | Chronology of Students’ Life | |

| 3 | 12.10.2016 | 37’37’’ | Challenging Topics for Students in the ‘Individual and Society’ Unit | |

| 4 | 18.10.2016 | 35’23’’ | Objects We Used in the Past | |

| 5 | 25.10.2016 | 37’22’’ | Why are we Learning about the Objects we Used in the Past? | |

| 6 | 1.11.2016 | 35’09’’ | I am Learning about my Past | What are Our Cultural Elements? |

| 7 | 2.11.2016 | 37’11’’ | Comparing the Cultural Elements of Different Countries | |

| 8 | 8.11.2016 | 39’12’’ | War of Independence | |

| 9 | 10.11.2016 | 35’39’’ | Ottoman Sultans and Reasons for the Fall of the Empire | |

| 10 | 17.11.2016 | 38’41’’ | World War I and the Fall of the Ottoman Empire | |

| 11 | 18.11.2016 | 35’23’’ | Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Invasions | |

| 12 | 22.11.2016 | 40’01’’ | War of Independence and the Congresses | |

| 13 | 29.11.2016 | 37’04’’ | Congresses and the Opening of the Turkish Grand National Assembly | |

| 14 | 30.11.2016 | 37’25’’ | Declaration of the Republic | |

| 15 | 6.12.2016 | 39’06’’ | Difference of the Republic from the Empire | |

| 16 | 7.12.2016 | 37’35’’ | The Place Where we Live | Cardinal and Intercardinal Points |

| 17 | 13.12.2016 | 51’46’’ | How can we Find our Way without a Compass? | |

| 18 | 14.12.2016 | 42’37’’ | What is in the Different Sides of our Classroom? | |

| 19 | 28.12.2016 | 24’08’’ | How can we Determine the Weather Conditions with a Thermometer? | |

| 20 | 29.12.2016 | 36’36’’ | Drawing a Sketch and Finding Locations in the Sketch | |

| 21 | 30.12.2016 | 26’44’’ | How Can we Use the Sketch of Our School? | |

| 22 | 3.1.2017 | 41’51’’ | Virtual Trip to the Meteorology Center | |

| 23 | 10.1.2017 | 41’17’’ | From Production to Consumption | Our Requirements and Wishes |

| 24 | 12.1.2017 | 39’09’’ | Identifying our Requirements and Wishes with a Shopping List | |

| 25 | 17.1.2017 | 41’34’’ | Income-Expense List and the Things to be Considered while Shopping | |

| 26 | 14.2.2017 | 42’10’’ | The Journey of Cotton Production | |

| 27 | 15.2.2017 | 39’35’’ | Occupations and their Characteristics | |

| 28 | 21.2.2017 | 35’36’’ | Classification of Occupations | |

| 29 | 23.2.2017 | 40’59’’ | Internet research on the history of technological instruments | |

| 30 | 24.2.2017 | 38’35’’ | We are Lucky to have it | Preparing a timeline about technological instruments |

| 31 | 27.2.2017 | 25’55’’ | Analyzing the overhead projector as a technological instrument | |

| 32 | 1.3.2017 | 34’10’’ | Searching for technological instruments in encyclopedias | |

| 33 | 7.3.2017 | 30’29’’ | Adding technological instruments to the timeline | |

| 34 | 8.3.2017 | 31’53’’ | Completing the timeline on technological instruments |

The schedule of the study started with a scan of the literature regarding the problems the students with normal hearing abilities and students with hearing loss in Social Studies classes in public schools encountered. It was continued with the planning, analysis and evaluation of the SSSS practices. The problems in the SSSS were identified, and the decision on the next step to address these problems was determined with a validity committee. The solution found was supported by the literature. Monthly meetings with the classroom teachers were included in this schedule.

During the study, students were provided with support services on Social Studies twice a week. The remaining days were allocated to support services in Turkish language, Science and Mathematics. In the study, 26 sessions of SSSS were performed, and each lasted approximately 35 minutes. Dates and durations of the topics studied within the SSSS are provided in Table 1.

As detailed in Table 2, the “I Know Myself,” “I am Learning about my Past,” “The Place Where we Live,” “From Production to Consumption” and “We are Lucky to have it” units were studied parallel to the program administered in public schools during the study period.

Six interviews were conducted with the classroom teachers during the study period. These were unstructured interviews, three of which aimed to determine the support service topics and the two of which aimed to plan the period. Two semi-structured interviews were conducted at the end of the semester for evaluation. The researcher attended the monthly meetings after determining the SSSS topics. Within these interviews, students’ performance was discussed with the teachers and the topics to be studied were identified. Students were asked about the topics they wanted to be repeated in the SSSS practices, and the topics and concepts mentioned by the students were reemphasized.

Interventions were performed through discussions using documents, photos, real objects, movies, timelines and computers on topics and concepts that students did not understand during classes. Following the interventions, 18 validity meetings were held, during which possible solutions to the problems were discussed (Table 2). The meetings listed between 1 and 12 in Table 2 below involved decisions made about solutions suggested for the problems students encountered. The meetings listed between 13 and 18 involved decisions on monitoring and evaluation.

Table-2. Contents of the Validity Meetings

| Item No. | Date | Duration | Content |

| 1 | 19.10.2016 | 20’12’’ | Problems related to explaining the concepts were identified. It was decided that more examples of the concepts should be provided. |

| 2 | 26.10.2016 | 53’21’’ | Objects used in the past were found to have very few contributions. It was decided that students would identify the objects they used in their lives and work on their conditions in the past. |

| 3 | 01.11.2016 | 20’33’’ | It was identified that students only gave examples from the course book regarding cultural elements. It was decided that they would make comparisons with different cultures. |

| 4 | 09.11.2016 | 19’55’’ | It was identified that students were able to make very few explanations about the War of Independence. It was decided that the situation before the War of Independence would be discussed with a timeline. |

| 5 | 23.11.2016 | 16’06’’ | It was identified that students were able to list the Central and Allied powers, but they were unable to associate them with the invasions. It was decided that the students would watch documentaries about the invasions. |

| 7 | 08.12.2016 | 31’20’’ | It was identified that they mixed up the cardinal and intercardinal points. It was decided that students would write and display information on the directions around the classroom. |

| 8 | 15.12.2016 | 41’05’’ | Students stated that they would identify the stones and the anthills, but they were unable to express the direction that these indicated. It was decided that directions would be described through visual aids and explanations. |

| 9 | 22.12.2016 | 29’52’’ | It was identified that students did not know how to read thermometers. It was decided that instead of searching for weather conditions on the Internet every day, they would measure it with a thermometer and write it on the graph. |

| 10 | 29.12.2016 | 36’44’’ | Students were identified to draw sketches but they had difficulty using these sketches so it was decided that they would walk around the school. |

| 11 | 05.01.2017 | 20’30’’ | It was discussed that students inquired about the functions and reasons of the tools and machines in the meteorology station. |

| 12 | 13.01.2017 | 9’08’’ | It was determined that students mixed up needs and wishes. It was decided that students would prepare a shopping list and classify the items on the list as needs or wishes. |

| 13 | 19.01.2017 | 49’04’’ | Evaluating student improvement |

| 14 | 09.02.2017 | 47’27’’ | Analyzing conceptual development through the monitoring data |

| 15 | 16.02.2017 | 41’54’’ | Analyzing the development of the establishing of cause and effect relations through the monitoring data |

| 16 | 23.02.2017 | 18’16’’ | Analyzing the development of the time concept through the monitoring data |

| 17 | 02.03.2017 | 31’31’’ | Analyzing the development of problem-solving skills through the monitoring data |

| 18 | 09.03.2017 | 32’54’’ | Analyzing and approving the themes of the researcher |

During the validity committee meetings held throughout the study, special attention was paid to preparing activities that would enable students to conduct research, recognize and use evidence, perception of chronology, and establish cause and effect relations.

2.5. Data Sources

In this study, observations were video-recorded to record all data without delay. Unstructured and semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded to plan, discuss and evaluate the actions (Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2011). Archive documents on the audiological information of students and the process products that emerged during the interventions were analyzed. Also, a research diary was used to record the comments, feelings and thoughts about observed and heard events, as well as the reflections that were added to the interventions (Johnson, 2012).

2.6. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected between Oct. 7, 2016 and March 2, 2017. During the study, decoded audio and video recordings of SSSS were read, summarized and classified. Descriptive analysis was performed on the organized data with reflections related to the aim and questions of the study. Decoded data were compared to the other data and the relevant repeated situations were determined. These parts were combined to reach the themes and codes. As a result of the analyses, the following three salient themes were obtained: reaching the meaning of concepts, perceiving time, and critical reasoning (Johnson, 2012).

2.7. Validity, Reliability and Trustworthiness

A considerable amount of data were collected over a long period, and they were approved by the validity committee to increase the accuracy of findings. Special attention was paid to consistency in the data, the collection of data within the process, and data triangulation (Johnson, 2012). Decoded audio and video recordings were confirmed by a field expert for internal validity (Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2011).

3. Findings

In this study, problems students with hearing loss encountered were identified, and interventions were performed for potential solutions. In Social Studies classes, students encountered problems mainly associated with (a) acquiring the meaning of concepts, (b) perceiving time and (c) establishing critical reasoning. Findings are presented below regarding the problems students encountered, decisions regarding a potential solution for these problems, and also developments determined in the interventions after the decisions and monitoring process.

3.1. Problems Encountered in Acquiring the Meaning of the Concepts

To scaffold students to acquire the meaning of the concepts, they were encouraged to discuss the characteristics of the concepts and their places in our lives using photos, pictures, real objects, documentaries and movies.

Students were seen to encounter problems in determining the concepts they did not understand. For example, when students were asked to explain the concepts they did not understand, they expressed the title of the unit by saying “I Know my Past” (18/10/2016, Video 4). With respect to this problem, the titles within the unit were read and students were given options regarding the topics they wanted to talk about.

Students encountered problems in explaining concepts related to Social Studies. For example, to see our finger print, Dilara said: “You paint your finger with watercolor paint or press it against glass to see it on the smoke,” (Video,1:16’23’’). Dilara confused the word “vapor” with the word “smoke.” Students were shown photos of smoke and vapor and were asked to explain the difference between the two. Students in the Social Studies class were identified to describe various misconceptions. For example, during the lesson on objects used in the past, both students responded to the question “Are there any old objects in your house?” by saying “No” (Video,4:13’20’’). The researcher understood that the students had confused the concept of “old” with the concept of “used” and gave examples by saying: “In my house, there are some old objects. And there are my mother’s earrings.” (Video, 4:13’50’’). Following this example, Dilara said: “My grandmother used to have a wedding ring but they threw it away” (Video, 4:15’40’’). Students learned the meaning of the concept of “old” (according to time). While talking about the fact that the wedding rings in our family were objects from the past, Mahmut said, “My mother also had one from past to present,”

Video,4:14’35’’). He was observed to be using the name of the unit as a general name given to objects from the past. The expression “From Past to Present” was corrected as “from the past.” It was emphasized that this term was used for objects that are still valuable despite being old. In order for the students to be able to explain the concepts, they were taught to recognize and use the evidence strategy and there were talks on objects and photos. In the validity committee meeting held on Oct. 19, 2016 regarding problems related to the concepts, it was decided that students would be given the opportunity to present more examples on multidimensional and abstract concepts (Audio, 1). In subsequent interventions, students were observed to be able to express the topics and concepts they did not understand. Mahmut wanted to talk about “Our Cultural Values” and Dilara wanted to talk about “Our Holly Days” (Video,6:5’17’’).

During the study period, it was observed that misconceptions continued. For example, despite the fact that the relevant photo was displayed and discussed at the beginning of SSSS, Dilara responded to the question “Why don’t we use coal iron now?” by saying: “I don’t remember” (Video,5:17’35’’). The researcher gave a clue by asking what they used at home and Dilara responded by saying: “A real, electric iron” (Video, 5:17’45’’). After that, a discussion was held with students on the challenges of using coal iron in past times before the advent of electricity. With regard to this problem, in the validity meeting on Oct. 26, 2016, it was decided that students would identify objects from their lives and the conditions of these objects in the past would be studied (Audio, 2).

Following the SSSS in which the cultural elements were spoken about, as the students did not bring any objects from their lives, the rings and earrings that remained from the mother and grandmother of the researcher were analyzed. In response to the students’ question: “Why did they give them?” the following response was given: “In order to look at it and remember it in the future”.

During the lesson in which weather conditions were assessed, the fact that minus degrees are cold and positive degrees are hot was discussed. While analyzing the thermometer, in response to the question “Why are all degrees from +50°C to -40°C written on it?” Dilara said: “It did not fit” (Video,20:17’57’’). It was explained that the temperature never falls below -40°C in Turkey, but weather colder than -40°C could be experienced in the North and South poles. This finding suggests that when the past knowledge and experiences of students are limited, they are likely to misinterpret concepts.

To sum up, the problems students encountered in understanding the meanings of concepts were observed to be (a) explaining the concept, (b) remembering the concept, and (c) misconceptions. Regarding solutions to these problems, students were (a) modeled to identify the concepts they did not understand, (b) presented with examples of the meanings of the concepts, and (c) made able to discuss by displaying photos, documents, objects and events related to the concepts. In this way, students were encouraged to use and express the strategy of identifying and using reference sources.

3.2. Problems Related to the Perception of Time

In activities that support the students in perceiving time, discussions were made using photos, documentaries and movies, questions were asked, and timelines were prepared. In preparing the timelines, students were asked to write the dates when the events happened as well as the events that took place on those dates. The information acquired by the students and their statements were written on the timeline by the researcher or by themselves, and the photos were added. In this way, their ability to use the perception of chronology strategy was promoted.

Students were seen to have problems in identifying the events to be added to the timeline while preparing their life chronologies. Clues as prompts were given to students through the hints, such as “If your teacher has changed,” “if a friend left school,” and “if something important happened” After that, Dilara was able to identify an important event of the year by saying “We moved in 2012” (Video,3:22’30’’). Also, Dilara reminded Mahmut by saying: “Your brother was born” (Video, 3:25’00’’).

Another topic in which the concept of time was promoted was the “War of Independence.” To emphasize the time of the events, a documentary on the Ottoman Empire was shown. While watching the documentary, Dilara asked: “Does the Ottoman Empire no longer enter into wars?” (Video,8:15’07’’). This question may show that Dilara was not able to visualize the time periods when the events happened in her mind. In the validity meeting on Nov. 9, 2016 on this problem, it was decided that conditions before the War of Independence would be discussed through timelines (Audio recording, 4). Following this meeting, discussions were made with students and a timeline on sultans and wars, from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, started to be prepared. When students saw the photos in sequence, their participation improved. For example, Mahmut pointed at one of the Ottoman Sultans, Osman Gazi, and said: “Do you know where his shrine is? It’s in Bursa” (Video, 11:26’08’). After placing the photos of the sultans on the timeline, Dilara was observed starting to ask questions, saying: “Did the first born sons become sultans?” (Video,11: 26’22’’).

All in all, it was observed that the problems students encountered in perceiving time were as follows: (a) confusing the chronological order, (b) visualizing the past events in time, (c) associating times and events. In terms of the solution for these problems, students were (a) supported to be able to understand past events in their minds by watching documentaries and movies, (b) asked to prepare timelines to see a sequence of events, (c) asked to write the summary of events on the timeline, to add reminding pictures and graphs, and to express them so that the strategy of perception of chronology was used many times in different situations.

3.3. Problems Encountered in Critical Reasoning

From the start, students were encouraged to use the strategy of understanding critical reasoning. In order for students to associate events with each other, in addition to the audio and visual materials used they were provided with questions and discussions in which they could combine their existing knowledge with new knowledge. This interference aimed to encourage students to use the strategy of critical reasoning.

In the lesson on “The Objects we have Used from the Past until the Present,” Mahmut responded to the question of “Why do we look at old photos?” by saying: “We look at them when we miss things” (Video,4:22’07’’). The reason for looking at old photos was explained as being related to wondering about how our mother used to look when she was a child, learning about objects used in the past, and comparing them to objects we use in the present.

In some lessons, students were observed explaining events. However, they were not able to account for their reasons. Talking about weddings, Dilara said. “They are playing the drum,” but she was not able to explain the reason why (Video, 6:9’33’’). It was explained that the drum was played to inform people. It was stated that students were only able to give examples from the course book. Dilara said: “Cuisine is part of our cultural wealth, our home objects.” (Video,6:5’00’’). Mahmut added “Our holidays, folk dances, handcrafts.” (Video,6:5’08’’). Concerning these problems, in the validity committee meeting on Nov. 1, 2016, we decided that lessons would be planned on making comparisons with different cultures.

To scaffold students to understand the factors affecting cultural elements, comparisons of dances, cuisine and sports in different countries of the world were made, and the reasons behind why cultural elements changed from country to country were discussed. Students were observed explaining the cultural differences between Japanese and Turkish people by pulling the corners of their eyes and saying “the Japanese are like this” (Video, 7:20’30’’). Students were shown abstracts from Japanese folk dances and Japanese cuisine. They were asked to determine the differences between them. Explaining why the dances were different, Mahmut said: “Because they are Japanese.” At the end of SSSS, when students were asked why the cultures were different, Mahmut said, “Because their countries are different, not their lives.” Dilara said: “Because their locations are different” (Video,7:30’35’’).

Students had problems in understanding the War of Independence. The underlying reasons for this difficulty were that this process involved abstract concepts, such as “nation” “invasion” and “independence” and the knowledge of students regarding these concepts was quite limited. While watching the documentary on the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in Sogut and Domanic, Mahmut recalled that the students had gone on a trip to Sogut. Mahmut was then able to combine his existing knowledge of the event by saying “The tomb of Ertugrul Gazi was there” (Video,8:13’25’’). This example showed that for the students to combine existing knowledge with new knowledge, realization using audio and visual materials was not sufficient, and the teacher should remind them of past knowledge and experience.

Students were observed listing both the Central and the Allied powers in the same session; however, they were not able to associate them with the invasions. Regarding this topic, in the meeting on Nov. 23, 2016, we decided that students would watch documentaries about the invasions (Audio recording, 5). Following this decision, the students watched parts of the movie “120,” which described the journey of 120 young people to the eastern front. As the duration of the SSSS was limited, first the topic of the movie was explained to the students, and only the important events in the film were watched. Trying to associate events in the movie, Dilara was observed asking: “Why didn’t their mothers join the war?” Mahmut asked: “How does the man accompanying the children know the way?” and “Why are they checking attendance every evening?” (Video,13:24’52’’). The examples showed that audio-visual materials could contribute to the understanding of events, developing students’ ability to critical reasoning (Researcher diary, 7:322).

To evaluate the topic on the “War of Independence,” students were asked oral questions that they would respond to in writing. In response to the question “Why did the Turks migrate from Central Asia?” Mahmut said: “Because of the drought,” whileDilara said: “They fought in order to expand their land.” While a response was being given to the students, a related photo was displayed. The topic of “War of Independence” was discussed with slides, including photos and short descriptions of the events that took place from the Ottomans era to the War of Independence. The topic was discussed in a number of SSSS sessions. For the students to be able to link the events, each lesson started with the first slide. When Dilara saw the second photo she said, “If you had told me that it was the second photo, I would have written it” (Video,14:17’15’’). It was also noted that she tried to memorize the photos in sequence. This example showed that the students had difficulty in critical reasoning between events while explaining various concepts and that they required visual materials.

On the subject of basic needs, students were observed determining their basic needs. However, while preparing their shopping list, they mentioned the concepts that they remembered as being “shopping list,” “plug,” “invoice,” “tap,” and “television” (Video,23: 13’18’’). It was determined that students confused needs and wishes. It was then explained to the students that our wishes were the things we enjoyed, and we could write the objects that we liked on a wish list. Following this guidance, students wrote examples such as “touch phone,” “computer,” “tablet,” “large screen television,” “motorcycle,” and “laptop.” Video,23:13’56’’). The students were also asked to record the objects that they mentioned. When the list was completed, the students were asked to identify the differences between the two lists. Dilara tried to explain by saying, “Needs are clothing, accommodation. But wishes are objects.” Mahmut said, “Our needs are what we need and our wishes cost money” (Video,23:29’00’’). The students were asked to write examples of the basic needs of students. To help the students differentiate between needs and wishes, the question “Can we live without them?” was posed. In addition, sometimes the things we want may also be things we need. Concerning this problem, in the validity meeting on Jan. 13, 2017, we decided that the students would prepare a shopping list and classify the items on the list as “needs” or “wishes” (Audio, 12). The students were, therefore, asked to prepare shopping lists. The students were observed explaining the reason why we make shopping lists. The students were asked to classify the things on their list as “needs” and “wishes.” Some of the products they wrote in the “needs” list, such as “jam”, “biscuits”, “dessert” and “sausage”, were moved to the list of “wishes” explaining the reasons (Video,24:25’39’’).

The problems students encountered while critical reasoning were identified as (a) failing to identify the relationships that link events, b) failing to classify events according to their similarities and differences and c) having limited knowledge or experience of past events. Regarding the solution to these problems (a) special attention was paid to improving the knowledge and experiences of students in the classes, (b) questions that would link events were emphasized in all interventions and (c) students were taught by displaying the relations between events directly. In this way, the students were encouraged to use and express the strategy of determining cause and effect relations.

3.4. Developments Observed in the Students

To evaluate the development of the students in the themes they experienced, monitoring data were obtained between Feb. 9, 2017 and March 8, 2017. As a result of the analysis of the monitoring data, it was found that the SSSS interventions made various contributions to the students.

In the analysis of the monitoring data on acquiring the meaning of the concepts within the “Production, Distribution, Consumption” topic, Dilara said: “I would like to learn the season when bread is baked.” Mahmut said: “I don’t know how bread is distributed.” Thus, they were able to identify the concepts that they did not understand (Video,26:7’21’’). It was observed that Dilara was able to explain what a lawyer did by saying they “Defend rights” (Video,27:11’57’’). After the lesson in which occupations were determined, classifications were made with the students based on occupations in the areas of production, distribution and consumption. In response to the question “What does consumption mean?” Dilara said: “It means spending” (Video,28:16’00’’). It was observed that Mahmut cited “car” and “accumulator” as examples of technological tools used in transport (Video, 29: 07’00’’). Dilara cited “stethoscope”, “blood sugar measurement tool”, “sphygmomanometer” and “syringe” as examples of technological improvements in the field of health (Video,29: 07’22’’). Although the misconceptions of students continued, looking at the sample expressions, it was observed that accurate usage increased regarding explaining and defining concepts.

The participation of students in perception of chronology was analyzed, and positive improvements were observed in the use of time. In the SSSS, when the development of technology from past to present was considered, Mahmut said that he would like to analyze the development of automobiles, while Dilara said that she would like to examine the development of the overhead projector. It was observed that the students were able to search on the Internet and determine when and by whom the automobile and overhead projector were invented. In the lesson on Feb. 24, 2016, they were able to record their knowledge about these inventions on the timeline. Then, Dilara recorded the information she searched for on the Internet regarding the invention of the television on the timeline, adding the relevant photo (Video,33:20’57’’). Mahmut recorded the space shuttle on the timeline and said “Oh! First the television was invented and then the space shuttle.” So he was observed expressing the time difference (Video,33:27’22’’). Looking at the statements of the students, the findings suggest that the activities carried to contribute to the development of their perception of time.

In the study, significant changes were observed regarding the ability of students regarding established critical reasoning. After talking about the fact that cotton was grown in Adana and that Adana was in the Mediterranean Region, the students were asked: “Why isn’t cotton grown in Central Anatolia?” Mahmut responded by saying: “I know, because it is cold” (Video,26:17’19’’). Regarding the reason why cotton is transferred to factories, Dilara said it was “For use in first aid kits” (Video, 26:19’17’’). Regarding how occupations emerged, Dilara said it was “To make our life easier” (Video,27:21’53’’). After the students were given explanations that if a person made a product then they are involved in production, if they sell the product then they are involved in consumption, and if they transport the product then they are involved in distribution, Dilara said: “The driver takes people around” and she was observed adding it to occupations in the field of distribution (Video,28:24’50’’).

When analyzing the characteristics of the overhead projector as a technological tool, students were asked about the difference between natural and semi-transparent paper. Mahmut said the parchment paper “is thick” and was able to explain the difference (Video,31:6’42’’). The overhead projector started to be used with the parchment paper. After the prints were not projected onto the wall, Dilara said: “Let’s use the carbon paper” and suggested using the thinner tracing paper (Video,31:9’18’’). When the students were asked about the reason why the writing on the acetate using the acetate pen was visible, Dilara said: “The paper needs to be transparent” (Video,31:22’14’’). In the SSSS when students conducted research using encyclopedias, Mahmut found the Encyclopedia of Inventions and said, “Teacher, I found the technological products” (Video,32:13’45’’) and was observed starting to examine it. When Dilara found the information on the radio in the encyclopedia, she was observed making comparisons, saying “There is silly stuff on the Internet” (Video,32:22’00’). In light of the expressions of the students, it could be deduced that their contributions to critical reasoning had increased.

4. Discussion

In this study, the intervention process was planned and applied, the problems were identified, the next step to solve the problems was determined with the validity committee, and students’ improvement was monitored using the solution means, all according to the action research method. Action research enables analysis of the research process and also enables researchers to go back to solve the problems (Johnson, 2012). The solution for problems experienced by students with hearing loss enrolled in inclusion programs was performed. In this section, the findings of the study are discussed under the following titles, in line with the literature and research questions: (a) problems experienced in learning Social Studies concepts and (b) solution interventions regarding these problems.

4.1. Problems Experienced in Learning Social Studies Concepts

It was observed that the problems students encountered in learning concepts stemmed from the characteristics of the Social Studies course and the inability of participating students to use the strategies. Looking at the characteristics of the Social Studies course, it is seen that the course content was structured around 10 themes that improve critical thinking and that were identified according to National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) (1994) standards. It was seen that the course books prepared by the MoE (2016) according to these themes included visuals, knowledge and exercises, but they were insufficient for students with hearing loss. For example, there was a map to explain invasions during the War of Independence within the “War of Independence” subject. While this material was helpful for students with regular hearing abilities in understanding the topic, the map was insufficient for students with hearing loss. When discussing this subject, the locations of the invading countries were shown using recent maps and photos taken during the invasion were examined. Events were identified on the timeline and explained through informative texts. This could have stemmed from the delay in the development of linguistic skills due to hearing loss. Punch and Hyde (2010) finding that the conceptual development of students with hearing loss was slower than their peers with regular hearing supports the results of this study.

Along with the delay in linguistic skills and the restrictions of the course books, the main problem encountered in the study was the difficulty that students experienced in understanding Social Studies concepts. This problem is in line with the findings of Woolsey et al. (2009). In their study, Woolsey et al. (2009) reported that students with regular hearing abilities have difficulty in attaining meanings to concepts, as it is the first time they have heard many of the Social Studies concepts. In this study, it was observed that students were not able to explain the meanings of such concepts as “home” “country,” “nation,” and “Central Powers” despite the fact that they were able to express them. The common characteristics of these concepts were the fact that they are abstract, multidimensional and associative. Looking at the content of Social Studies, many concepts are seen to have these characteristics. For example, “home country” is an abstract concept. Students can understand this concept based on their knowledge that the country where they were born is their home country. The word “nation” could be an example of a multidimensional concept. For the students to understand the concept of “nation,” they should know that it refers to people who share a common culture, values and history. The term “Central Powers” could be an example of an associative concept. For students to understand the term “Central Powers,” they should draw an association with the “Allied Powers” and the advantage of making alliances. In the literature, it is discussed that these concepts could only be taught through education (cited from Mortarella by Doganay (2008)). In this study, students were observed memorizing the definitions of concepts, and the examples they gave were limited to the course book content. In the literature, there is a discussion that this problem stems from the fact that students are unable to associate the concepts with similar events in their lives. Consistent with this finding, Bailey et al. (2006) state that when the Social Studies concepts are not associated with real life, they are memorized without comprehension. Furthermore, the delays experienced in linguistic skills due to hearing loss have a negative effect on imagination and abstract thinking. They, therefore, restrict the sequencing and interpreting of events, as well as the critical reasoning and perceiving time (Eden, 2008; Punch and Hyde, 2010). It is well-known that all these skills have an essential role in learning concepts. Hence, two main elements could be cited as causing problems for students regarding acquiring the meaning of concepts and critical reasoning. One of these elements is the fact that Social Studies concepts are abstract and multidimensional and they also have associative characteristics. The other element is the fact that hearing loss restricts abstract and relative thinking (cited from Mortarella by Doganay (2008)). Despite the fact that this process requires conceptual teaching, the inadequacy of time allocated to the Social Studies course within the curriculum delays the solving of these problems. Fitchett and Heafner (2010) findings on the time allocated to Social Studies courses being less than language and mathematics courses support this belief. To develop these skills, students should be able to use the strategies of identifying and using reference sources, perception of chronology, and critical reasoning. The students who participated in this study were observed to be using these strategies insufficiently. This finding is compatible with the research conclusions of Bailey et al. (2006) who raised their concern that Social Studies strategies are not supported sufficiently. In this study, the time allocated to SSSS was limited to 80 minutes per week because SBSS was conducted along with the Science, Mathematics and Turkish courses, which is one of the limitations of this research. This limitation may restrict students’ exposure to the repetition and realization of Social Studies concepts and strategies. Interventions to solve these problems are discussed in the following section on the second question of the research.

4.2. Solution Interventions for Problems Encountered in Learning Social Studies Concepts

Interventions to address problems have been discussed around the contributions of teachers to critical thinking, the diversity of materials and activities, and strategy-based interventions. Teachers are at the center of the focus on developing critical thinking abilities. The research process was designed considering the role of teachers in the development of critical thinking in students. In the literature, some researchers recommended that subjects should be analyzed in detail when evaluating the knowledge of students (eg. Zarrillo (2012)). Despite her 21 years of experience, the researcher in the present study planned and implemented specific activities that would support the concepts identified in monthly interviews made with the classroom teachers before each SSSS.

SSSS interventions were supported with PowerPoint presentations, movies, documentaries, timelines, photos and real objects. The support that was continuously given in this way was observed to have improved student participation while enabling students to give meanings to concepts and question the reasons for events. There are ranges of discussions on these aspects in the relevant literature. For example, Steele (2008) emphasizes that when presenting Social Studies content to students with poor performance, associating the topic with the lives of the students, using PowerPoint presentations, and providing individual support in basic concepts led to positive results. Similarly, Alongi et al. (2016) points out that audio-visual documents, knowledge and information technologies contribute to critical perception in Social Studies classes. Buchanan (2015) reports that documentaries encourage students to think critically by presenting a different perspective on historical events in Social Studies classes. In this study, students with hearing loss benefited from PowerPoint presentations, movies, documentaries, timelines, photos and real objects in the teaching of Social Studies concepts.

In this study, in addition to material support, students were allowed to account for the reason for events and encouraged to discover the concepts that they were not able to understand with the help of appropriate questions. This finding is supported by the relevant literature that when students were asked questions in which they could combine their knowledge and experiences, when they were modeled in terms of their ways of thinking, or when they were asked to give reasons for the conclusions that they reached, their critical thinking skills improved (Browne and Keeley, 2007; Zarrillo, 2012).

In this study, the problems experienced by students in attaining the meaning of concepts, perceiving time, and critical reasoning, were attempted to be solved through encouraging them to use the strategies of identifying and using reference sources, perception of chronology and critical reasoning. With this attempt, students’ critical thinking skills could be supported by learning to support their expressions with scientific evidence, talking about events in a rational sequence, and estimating the relationships between them. Strategy enables the attainment of the ability to use knowledge and experiences, acquire and understand knowledge, make self-evaluations, and learn independently by changing thoughts where necessary as well as developing critical thinking skills (Jones et al., 1987; Bransford et al., 2000). In light of the findings, we can deduce that the students with hearing loss need to use various strategies to deal with Social Studies concepts and they benefitted from strategy teaching.

When acquiring the meaning of concepts within the study process, students were seen to have misconceptions when they were asked to explain a concept or to make estimations about its content. To overcome this problem, students were encouraged to use the strategies of identifying and using reference sources. Students were encouraged to have discussions using objects, photos and movies that supported the concepts. The finding by Buchanan (2015) on discussing the contents of concepts using the strategy of identifying and using reference sources to minimize misconceptions could be listed as a similar intervention. Obenchain and Morris (2011) suggest that identifying and using reference sources through written and audio-visual documents as primary resources promote reasoning.

The timelines used in the present research for the students to make chronological sequencing and visualize the concept of the past in their minds enabled them to see the relationship between events. This finding is consisted with the literature through the statement that explaining events by locating them in time and space enables inquiry through the recognizing of time differences and relationships and ensured critical thinking, respectively (Levstik and Barton, 2001). In the present study, students were shown movies and documentaries on historical events to demonstrate that the events occurred in a sequence. As a result, students were observed comparing the events that they already knew about the events that they watched. This finding is supported in light of the research conducted by Eden (2008) which revealed that visual aids are not sufficient on their own and that sequenced cards, which show development within the process, improve the perception of time.

In this study, students were encouraged to use strategies to critical reasoning. Steele (2008) states that for the students to ascribe meanings to new experiences, meaningful learning could be realized by relating knowledge and experiences with each other and discussing them. It was observed that the knowledge and experiences of students regarding historical events were quite limited. As a result, after activities to structure the limited past knowledge of historical events were performed in the study, students were more able to discuss the events.

Although hearing loss leads to delays in the development of linguistic skills and academic skills, respectively, students with hearing loss are believed to attain critical thinking skills, like their peers with regular hearing abilities, when they are provided with more visual materials, more repetition, adoptions in Social Studies texts, and opportunities to use the strategies. This finding is compatible with Girgin (2013) and Karasu (2017) finding indicating that students with hearing loss, when compared to their peers with normal hearing abilities, require more visuals explaining events, more repetition, and the adoption of academic texts. Girgin (2013) and Karasu (2017) recommend that when these requirements are addressed, improvements in both linguistic and academic skills are experienced.

The aforementioned means of solution involved interventions regarding support services for students with hearing loss enrolled in public schools. It has been observed that support services are not provided systematically in Turkey. This reality leaves classroom teachers, who try to conduct intensive education programs in crowded public school classrooms, quite isolated (Marschark et al., 2002).

Students with hearing loss enrolled in public schools were observed to require systematic support to acquire knowledge within this classroom environment. To address this issue, students’ needs were identified in the study, adaptions were made for them to attain knowledge, and web-based primary resources were used along with visual presentations (Hicks et al., 2004; Girgin, 2013; Karasu, 2017) . Thanks to this, the development of critical thinking skills in the students was promoted by providing them with activities that they could do multiple times in different contents to use the strategies of identifying and using reference sources, perceiving time, and establishing critical reasoning.

5. Conclusion

In this study, 4th-grade students with hearing loss enrolled on public schools were identified to have problems in acquiring the meaning of concepts in Social Studies classes, perceiving time, and critical reasoning. It is believed that using the strategies of identifying and using reference sources, perception of chronology, and critical reasoning in the interventions to address these problems would contribute to the attainment of critical thinking skills. For the development of these strategies, materials and repetitions are believed to be essential, and this requires more time. Because of the limited number of participants, the results of this study could not be generalized, but these findings should be regarded as preliminary and with a larger cohort of participants the methodology employed here could be replicated.

Recommendations on SSSS interventions for students with hearing loss could be as follows: Increasing the duration of support services could enable students to use the strategies more frequently. To improve critical thinking in support services, interventions could be made based on student research on the concepts. The development of students with support service interventions could be assessed through formal or informal tools and systematic intervals. In future research, the strategies of Social Studies courses could be studied simultaneously in SSSS and classroom environments. The contributions of support services might be presented through longitudinal research.

References

Akay, E., 2016. An investigation of the mentorship process for educators who provide special education support services for hearing-impaired students in inclusive education. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Anadolu University, Eskisehir.

Aksid, F. and C. Sahin, 2011. The effect of active learning on academic achievement and attitudes in geography teaching. Western Anatolia Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(4): 1-26. View at Google Scholar

Alongi, M., B.C. Heddy and G.M. Sinatra, 2016. Real world engagement with controversial issues in history and social studies: Teaching for transformative experiences and conceptual change. Journal of Social Science Education, 15(2): 26-41. View at Google Scholar

Bailey, G., E.L.J. Shaw and D. Hollifield, 2006. The devaluation of social studies in the elementary grades. Journal of Social Studies Research, 30(2): 18-29.

Bolognini, N., C. Cecchetto, C. Geraci, A. Maravita, A. Pascual-Leone and C. Papagno, 2012. Hearing shapes our perception of time: Temporal discrimination of tactile stimuli in deaf people. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(2): 276–286. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Boucher, M.J., 2010. Maps: Developing critical thinking skills for deaf students in a social studies curriculum. Unpublish Master Thesis. University of California, San Diego.

Bransford, J.D., A.L. Brown and R.R. Cocking, 2000. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience and school. Washington D.C: National Academy Press.

Browne, N. and S. Keeley, 2007. Asking the right questions: A guide to critical thinking. 8th Edn., Engle-Wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Buchanan, L.B., 2015. Fostering historical thinking toward civil rights movement counter-narratives: Documentary film in elementary social studies. Social Studies, 106(2): 47–56.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Doganay, A., 2008. Teaching principles and methods. 2nd Edn., Ankara: Pegem Academy.

Donnelly, V. and A. Watkins, 2011. Teacher education for inclusion in Europe. Prospects: Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 41(3): 341–353.View at Publisher

Eden, S., 2008. The effect of 3D virtual reality on sequential time perception among deaf and hard-of-hearing children. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(4): 349-363. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Ennis, R.H., 2011. The nature of critical thinking: An outline of critical thinking disposition and abilities. Retrieved from http://faculty.education.illinois.edu/rhennis/documents/TheNatureofCriticalThinking_51711_000.pdf [Accessed 19.6.2017].

Fitchett, P.G. and T.L. Heafner, 2010. A national perspective on the effects of high-stakes testing and standardization on elementary social studies marginalization. Theory and Research in Social Education, 38(1): 114-130.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Gagné, R.M. and M.P. Driscoll, 1988. Essentials of learning for instruction. 2nd Edn., N.J: Prentice Hall.

Geers, A., E. Tobey, J. Moog and C. Brenner, 2008. Long-term outcomes of cochlear implantation in the preschool years: From elementary grades to high school. International Journal of Audiology, 47(2): S21-S30. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Gelzheiser, L.M. and J. Meyers, 1991. Reading instruction by classroom, remedial and resource room teachers. Journal of Special Education, 24(4): 512-526. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Girgin, U., 2013. Teacher strategies in shared reading for children with hearing impairment. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 53: 249-268. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Glazzard, J., A. Stokoe, A. Hughes, L. Netherwood and J. Neve, 2010. Teaching primary special educational needs. Exeter: Learning Matters Ltd.

Guleryuz, Ş.O., 2009. Evaluation of disabled students who are in inclusive education and their problems which are faced with their peers. Unpublished Master Thesis, Selcuk University, Konya.

Gurgur, H., 2008. Examination of collaborative teaching approach in a mainstreamed elementary classroom. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Ankara University, Ankara.

Hawkman, A.M., A.J. Castro, L.B. Bennett and L.H. Barrow, 2015. Where is the content?: Elementary social studies in preservice field experiences. Journal of Social Studies Research, 39(4): 197-206. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Hess, D.E., 2002. Discussing controversial public ıssues in secondary social studies classrooms: Learning from skilled teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education, 30(1): 10-41. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Hesse-Biber, S.N. and P. Leavy, 2011. The practice of qualitative research. 2nd Edn., Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication, Inc.

Hicks, D., P. Doolittle and J.K. Lee, 2004. Social studies teachers' use of classroom-based and web-based historical primary sources. Theory & Research in Social Education, 32(2): 213-247. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Ikuenobe, P., 2001. Teaching and assessing critical thinking abilities as outcomes in an informal logic course. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(1): 19-32.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Johnson, A.P., 2012. A short guide to action research. 4th Edn., USA: Pearson Education Inc.

Jones, B.F., A.S. Palincsar, D.S. Ogle and E.G. Carr, 1987. Strategic teaching and learning: Cognitive instruction in the content areas. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Karabulut, S., 2012. How to teach critical-thinking in social studies education: An examination of three NCSS journals. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 49: 197-212. View at Google Scholar

Karasu, H.P., 2017. Examining activities concerning the use of words encountered in content area courses in writing by children with hearing loss. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(11): 48-64. View at Google Scholar

Kargin, T. and B. Baydik, 2002. Investigating the attitudes of hearing students towards mainstreamed hearing impaired students in terms of various variables. Ankara University Faculty of Educational Sciences Journal of Special Education, 3(2): 27-39.

Kayaoglu, H., 1999. The effect of informational program on attitudes of normal class teachers toward hearing impaired children in mainstreaming environment. Unpublished Master Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara.

Levstik, L.S. and K.C. Barton, 2001. Doing history: Investigating with children in elementary and middle schools. 2nd Edn., Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Learning to Teach History as Interpretation.

Marschark, M., A. Young and J. Lukomski, 2002. Perspectives on inclusion. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 7(4): 187–188. View at Google Scholar

Mastropieri, M.A. and T.E. Scruggs, 2010. The inclusive classroom. 4th Edn., N.J: Pearson Education, Inc.

Mayberry, R.I., 2002. Cognitive development in deaf children: The interface of language and perception in neuropsychology. S.J. Segalowitz and I. Rapin (Eds), Handbook of neuropsychology. 2nd Edn., Amsterdam: Elsevier, 8: 71-107.

Ministry of Education, 2016. Elementary 4th grade social studies teacher guide book. S. Cebir Burhan (Ed). Ankara: Koza Publication, Inc.

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), 1994. Curriculum standards for social studies: Expectations of excellence. Washington D.C: NCSS.

Obenchain, K.M. and R.V. Morris, 2011. 50 social studies strategies for K-8 classrooms. 3rd Edn., Boston: Pearson.

Polat, S., 2015. Content analysis of the studies in Turkey on the ability of critical thinking. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 15(3): 659-670.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Punch, R. and M. Hyde, 2010. Children with cochlear implants in Australia: Educational settings, supports, and outcomes. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(4): 405-421.View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Seyihoglu, A. and A. Kartal, 2010. The views of the teachers about the mind mapping technique in the elementary life science and social studies lessons based on the constructivist method. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 10(3): 1637-1656.View at Google Scholar

Shepherd, C. and E. Acosta-Tello, 2015. Differentiating instruction: As easy as one, two, three. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 12(2): 95-100. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Sievers, A., 2005. The social studies classroom: Attitudes and perspective from the deaf and hard of hearing students through literature. Unpublished Master Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology: New York.

Steele, M.M., 2008. Teaching social studies to middle school students with learning problems. Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 81(5): 197-200. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Woolsey, M.L., T.J. Herring and S.T. Satterfield, 2009. Social studies instruction in signing programs for deaf and hard of hearing students: An ecobehavioral assessment. American Annals of the Deaf, 154(4): 400-412. View at Google Scholar | View at Publisher

Zarrillo, J.J., 2012. Teaching elementary social studies: Principles and applications. 4th Edn., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.