Using Genre-based Approach to Overcome Students’ Difficulties in Writing

1English Education Department, Universitas HKBP Nommensen, Medan, Indonesia.

2,4English Education Department, Universitas Simalungun, Pematangsiantar, Indonesia.

3Faculty of Philology, Hanoi Pedagogical University 2, Vinh Phuc, Vietnam.

Abstract

Because of the importance of the English language, the government of Indonesia always aims to apply approaches that are anticipated to be appropriate for education levels and students’ ability, not only in attaining knowledge but also in relation to their personality and integrity in regard to using the knowledge gained in their future day-to-day life. A genre-based approach (GBA) is used to conduct classroom instruction and genre-based learning practices. One expert, Yan, argues that this approach has been popular since the 1980s, alongside the idea that students and writers could benefit from researching various types of written language. The GBA plays an important role in overcoming students’ difficulties in writing achievement. Because a descriptive quantitative method was adopted in this research, observation, document analysis (writing test), and interviews were conducted as data collection for the implementation of this GBA. After analysis of the data, the researchers came to the conclusion that this paper would be beneficial as a tutorial in helping students decide what ideas could be included in their writing, especially in classroom practice, to create meaningful texts. This GBA model can be used as a framework to enable teachers and students to develop their writing skills. It is hoped that this model can become a classroom strategy in allowing teachers and students to achieve a higher level of writing skill.

Keywords:GBA, Teaching, Text, Tutorial, Strategy, Writing skills.

Contribution of this paper to the literature: This study contributes to existing literature by presenting the strength of Genre-based Approach or known as GBA to linguistics especially for language teaching in order to support students’ problems and improve students’ ability in writing.

1. Introduction

Learning the English language is a key goal to be achieved for many students around the world. However, to achieve this goal, many students fail to learn English because of their background as non-English speakers. To conduct the process of learning English for non-English-speaking students is a very difficult assignment for teachers. Students are expected to be able to communicate in both the written and oral form of English (Pardede & Herman, 2020![]() ).Students always use their mother language in learning and for some other activities, which is why there are many solutions, strategies, and methods tailored to English teaching around the world. These are structured to train students to address their future, and they must have the skills to adapt to constantly evolving and increasingly challenging environments. Teachers should concentrate on teaching those skills critical to the development, use, and usage of knowledge in the learning process.

).Students always use their mother language in learning and for some other activities, which is why there are many solutions, strategies, and methods tailored to English teaching around the world. These are structured to train students to address their future, and they must have the skills to adapt to constantly evolving and increasingly challenging environments. Teachers should concentrate on teaching those skills critical to the development, use, and usage of knowledge in the learning process.

Centered on the educational system for English language teaching in Indonesia, there are four skills that students can acquire in the educational process: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. To comprehend these four skills, vocabulary is most essential for all students. Vocabulary is the basis of English lessons that leads to an understanding of what we write (Herman, Sibarani, & Pardede, 2020![]() ; Sinaga, Herman, & Pasaribu, 2020

; Sinaga, Herman, & Pasaribu, 2020![]() ). With the use of vocabulary, these four skills can be learned easily. However, writing is a complicated skill as well as a craft. Through writing, the reader can determine the writer’s personality. It is understood that personality comes in two forms, namely introvert and extrovert. Those with an introvert personality usually describe (in the form of writing) everything as simply and briefly as possible, which is why the reader will acquire little information from the writing. It means that those people’s writings cannot be used fully as a source of information. In contrast, those with an extrovert personality will explain/describe everything as completely as possible. Therefore, information shared through their writing will be more informative than that of the introverted writer. Viewing this from the basis of language, it means that those with an introvert personality are less successful in their use of language.

). With the use of vocabulary, these four skills can be learned easily. However, writing is a complicated skill as well as a craft. Through writing, the reader can determine the writer’s personality. It is understood that personality comes in two forms, namely introvert and extrovert. Those with an introvert personality usually describe (in the form of writing) everything as simply and briefly as possible, which is why the reader will acquire little information from the writing. It means that those people’s writings cannot be used fully as a source of information. In contrast, those with an extrovert personality will explain/describe everything as completely as possible. Therefore, information shared through their writing will be more informative than that of the introverted writer. Viewing this from the basis of language, it means that those with an introvert personality are less successful in their use of language.

Delivering information through good writing requires consideration of certain elements: comprehension of the material, diction, and grammar (Permana, Zuhri, & Fauris, 2013![]() ). Understanding the material means good development and organization of ideas. In order to get a sense of writing, accurate diction is required. In addition, the final suggestion is that the text's time should be sufficient for correct grammar. In reality, however, writing always presents a huge barrier since students have difficult in producing good writing. Some students still produce poor writing and have difficulty expressing their ideas through writing, although others have average proficiency in English. Grammatically correct text and the application of knowledge to particular contexts and purposes are essential in writing. A genre focus can be a framework to help students improve their writing in particular communicative events.

). Understanding the material means good development and organization of ideas. In order to get a sense of writing, accurate diction is required. In addition, the final suggestion is that the text's time should be sufficient for correct grammar. In reality, however, writing always presents a huge barrier since students have difficult in producing good writing. Some students still produce poor writing and have difficulty expressing their ideas through writing, although others have average proficiency in English. Grammatically correct text and the application of knowledge to particular contexts and purposes are essential in writing. A genre focus can be a framework to help students improve their writing in particular communicative events.

The use of genre is obvious in Indonesia’s new curriculum (known as Kurikulum 2013 or K-13), where it focuses more on the ability of students in writing texts. Text may be categorized into three parts: communication, organizational structure, and language characteristics. The aim of conversation or social context is to voice, write, or produce a text. The document's hierarchical or general structure is the organization of the document or the text. Language properties or lexical grammar include items such as the grammar, terminology, and connectors used.

Herman (2014![]() ) implies that genre applies to more unique types of writing, such as media reports or instructions. In addition, Herman (2014

) implies that genre applies to more unique types of writing, such as media reports or instructions. In addition, Herman (2014![]() ) stated that genres represent the categories of operations including the personal message, the student essay, and the text type word, which are identical in linguistic nature, such as the procedure, anecdote, and explanation. Types of text can be divided into 12 categories, namely recount, report, discussion, explanation, exposition analytical, exposition hortatory, news item, spoof, narrative, procedure, description, and review (Herman, 2014

) stated that genres represent the categories of operations including the personal message, the student essay, and the text type word, which are identical in linguistic nature, such as the procedure, anecdote, and explanation. Types of text can be divided into 12 categories, namely recount, report, discussion, explanation, exposition analytical, exposition hortatory, news item, spoof, narrative, procedure, description, and review (Herman, 2014![]() ; Pardede & Herman, 2020

; Pardede & Herman, 2020![]() ; Rajagukguk, Herman, & Sihombing, 2020

; Rajagukguk, Herman, & Sihombing, 2020![]() ; Sinaga, Herman, & Hutauruk, 2020

; Sinaga, Herman, & Hutauruk, 2020![]() ) .

) .

Since genre is adapted in learning process in schools, the various genres above can hopefully be taught purposefully, especially in writing through a GBA. Martin (1992![]() ) clarified that the GBA is based on the assumption that, in order to complete written genres, students require guided practice; thus, genre types should be taught explicitly by the empirical analysis of models, the study of genre elements and their pattern, and the cooperative then solo creation of examples. Besides, it has been mentioned that clear, teacher-directed pedagogy is especially essential for minority students. They argue that through the explicit instruction of socially dominant genres, the powerless and marginalized in society will achieve legitimate access to influence.

) clarified that the GBA is based on the assumption that, in order to complete written genres, students require guided practice; thus, genre types should be taught explicitly by the empirical analysis of models, the study of genre elements and their pattern, and the cooperative then solo creation of examples. Besides, it has been mentioned that clear, teacher-directed pedagogy is especially essential for minority students. They argue that through the explicit instruction of socially dominant genres, the powerless and marginalized in society will achieve legitimate access to influence.

Some researchers have carried out studies of GBA. A survey on the use of the GBA and its impact on the writing performance and attitudes of Thai engineering students were published in 2012. This study showed that participants were happy with educational methods, tasks, and exercises. They felt more confident in writing, in general. A different analysis was made by Yuliani (2012![]() ). She showed that application of the GBA method of teaching narrative writing enhanced student narrative texts throughout, step by step, in forms of schematic constructs and grammatical structures. Therefore, this research was done to investigate the stages in GBA and to determine to what extend GBA can help students’ difficulties in writing.

). She showed that application of the GBA method of teaching narrative writing enhanced student narrative texts throughout, step by step, in forms of schematic constructs and grammatical structures. Therefore, this research was done to investigate the stages in GBA and to determine to what extend GBA can help students’ difficulties in writing.

However, application of the GBA in schools is still infrequent and this has motivated the writer to discuss its application to address students' challenges in composing a book. Moreover, the researchers hope that this research can be a reference for readers, especially in improved the teaching of English to non-English-speaking students.

2. Theoretical Review

2.1. Systemic Functional Linguistics

There is a whole variety of advancements used by linguists to recount linguistic diversity. Present linguistics texts include Ferdinand Saussure, Firthian Linguistics by J.R. Firth, and Systemic Linguistics by M.A.K. Halliday. Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) is a language hypothesis that is the same as an idea used to establish meaning, placed within the context of customs circumstances. SFL was created by Halliday (1985![]() ), a professor of linguistics at the University of Sydney, Australia.

), a professor of linguistics at the University of Sydney, Australia.

SFL is also known as systemic functional grammar (SFG), which is in conflict with language education. It is dissimilar to the entire preceding form of sentence structure because it construes language as interconnected sets of alternatives for creating sense and tries to present an obvious association with roles and grammatical structure (Halliday, 1994![]() ). Functional linguists investigate a text, either oral or in print, from a functional viewpoint. A text is “a melodious compilation of sense suitable to its perspective” (Butt, Fahey, Feeze, Spinks, & Yallop, 2000

). Functional linguists investigate a text, either oral or in print, from a functional viewpoint. A text is “a melodious compilation of sense suitable to its perspective” (Butt, Fahey, Feeze, Spinks, & Yallop, 2000![]() ). A comprehensive perception of a text is always unworkable without any hint of its viewpoint. The meaning can be measured from two perspectives: the customs meaning and the circumstances context; the previous passages on the broad sociocultural context of philosophy, communities, and associations; and the final narratives on the detailed sociocultural conditions (Droga & Humphrey, 2002

). A comprehensive perception of a text is always unworkable without any hint of its viewpoint. The meaning can be measured from two perspectives: the customs meaning and the circumstances context; the previous passages on the broad sociocultural context of philosophy, communities, and associations; and the final narratives on the detailed sociocultural conditions (Droga & Humphrey, 2002![]() ). The situation distinguishing between texts, namely region, tenor, and mode can be explained by means of admiration for circumstances. The field is the connection between writer, or listener and reader; mode is about the channel of communication (Butt et al., 2000

). The situation distinguishing between texts, namely region, tenor, and mode can be explained by means of admiration for circumstances. The field is the connection between writer, or listener and reader; mode is about the channel of communication (Butt et al., 2000![]() ). Field is a reference point for what is to be spread or printed. These three aspects show the three main goals and so-called language metafunctions.

). Field is a reference point for what is to be spread or printed. These three aspects show the three main goals and so-called language metafunctions.

2.2. Definition of Genre

A particular category of speech activity (integrated written text) is described by Richards, Platt, & Platt (1993![]() )and is evaluated by a speaking community, as one form, for instance prayers, preaching, discussions, music, interviews, poems, posts, and stories. The genre is typically defined by its aspects of communication objective(s) in standard, similar themes, conventions (rhetorical form, lexico-grammar, and other textual features), contact networks (e.g., verbal, digital, printed version) of audience categories, and often the positions of authors and readers. As per Swales (1990

)and is evaluated by a speaking community, as one form, for instance prayers, preaching, discussions, music, interviews, poems, posts, and stories. The genre is typically defined by its aspects of communication objective(s) in standard, similar themes, conventions (rhetorical form, lexico-grammar, and other textual features), contact networks (e.g., verbal, digital, printed version) of audience categories, and often the positions of authors and readers. As per Swales (1990![]() ), a genre includes communicative activities that divide a range of broad objectives. These aims are recorded by the parent discourse society's qualified experts and lay the genre's foundation. This foundation shapes the basic structure of the discourse and manipulates and limits the probability of substance and manner. The expansive aim is both a classified measure and the purpose of preserving the genre's scope, as here constructed hardly based on known metaphorical behavior. Following the purpose of the genre samples, the structure, form, content, and potential audience have different relations. The parent discourse society would consider the exemplar as ideal if all major possibilities are achieved. (p. 58) .

), a genre includes communicative activities that divide a range of broad objectives. These aims are recorded by the parent discourse society's qualified experts and lay the genre's foundation. This foundation shapes the basic structure of the discourse and manipulates and limits the probability of substance and manner. The expansive aim is both a classified measure and the purpose of preserving the genre's scope, as here constructed hardly based on known metaphorical behavior. Following the purpose of the genre samples, the structure, form, content, and potential audience have different relations. The parent discourse society would consider the exemplar as ideal if all major possibilities are achieved. (p. 58) .

Hyland (2003![]() ) suggests that the genre only refers to well-known language uses. That is a concept that we are using as a collective term for partnership texts and how authors use vocabulary to respond to and create texts for specific circumstances.

) suggests that the genre only refers to well-known language uses. That is a concept that we are using as a collective term for partnership texts and how authors use vocabulary to respond to and create texts for specific circumstances.

2.3. Genre Research

Genre research is an evolving interdisciplinary approach to studying documents, both spoken and textual, based on linguistics, anthropology, psychology, and sociology. Genre observers attempt frequent grammatical procedure trends, critical vocabulary, and content creation in exact text styles (Bradford-Watts, 2003![]() ). There has been considerable interest during the last ten years in the genre-based study of various forms of documents. This approach was derived directly from dialogue and document interpretation and was commonly used in English for specific purposes (ESP).

). There has been considerable interest during the last ten years in the genre-based study of various forms of documents. This approach was derived directly from dialogue and document interpretation and was commonly used in English for specific purposes (ESP).

Reliable linguists understand the author's aim in constructing a certain genre. In the other direction, genre analysis does not depend exclusively on persuading grammatical forms' selection but rather on metaphorical aspects. Robinson (1991![]() ) argues that the orientation explains the "objective of the writer towards the broader expert community to which the author belongs." The genre therefore not only means the form of text, but also the role of the document in its culture. This helps to research the cultural institutions.

) argues that the orientation explains the "objective of the writer towards the broader expert community to which the author belongs." The genre therefore not only means the form of text, but also the role of the document in its culture. This helps to research the cultural institutions.

Dudley-Evans (1987![]() ) suggests that its primary purpose is pedagogical in that it provides "a versatile prescription resulting from an interpretation that allows recommendations on the outline, ordering, and vocabulary appropriate for exacting writing or speaking activities." Hopkins & Dudley-Evans (1988

) suggests that its primary purpose is pedagogical in that it provides "a versatile prescription resulting from an interpretation that allows recommendations on the outline, ordering, and vocabulary appropriate for exacting writing or speaking activities." Hopkins & Dudley-Evans (1988![]() ) conclude that the early theory of genre analysis is "a straightforward clarification of how texts are organized." Hyland (1992

) conclude that the early theory of genre analysis is "a straightforward clarification of how texts are organized." Hyland (1992![]() ) states that "genre analysis research [sic] how vocabulary is used in an actual situation." Bhatia (1991

) states that "genre analysis research [sic] how vocabulary is used in an actual situation." Bhatia (1991![]() ) sees genre analysis as an "analytical framework which exposes not simply the functional form-function associations but also donates considerably to our comprehending of the cognitive structuring of information in precise parts of language use, which may help the ESP practitioners to develop suitable activities potentially important for the accomplishment of desired communicative results in specialized academic or profession areas." The analysis of genre not only has a latent pedagogical character but may also explain the communication structure for a specific genre in this regard. This incorporates genre analysis with analogous socio-cognitive and cultural clarifications. It defines the surface vocabulary and not the language form (Bhatia, 1991

) sees genre analysis as an "analytical framework which exposes not simply the functional form-function associations but also donates considerably to our comprehending of the cognitive structuring of information in precise parts of language use, which may help the ESP practitioners to develop suitable activities potentially important for the accomplishment of desired communicative results in specialized academic or profession areas." The analysis of genre not only has a latent pedagogical character but may also explain the communication structure for a specific genre in this regard. This incorporates genre analysis with analogous socio-cognitive and cultural clarifications. It defines the surface vocabulary and not the language form (Bhatia, 1991![]() ).

).

2.4. The Notion of Genre

The word genre was originally taken from the Latin, genus, which means kind or sort or class. There are very many views about genre from the early 1980s and, over the years, there have been several descriptions of it. All of these meanings are stressed in the sense of SFL. Martin (1985![]() ) said that genres had become the way things are performed as the vocabulary is used to do them. Yates, Orlikowski, & Okamura (1999

) said that genres had become the way things are performed as the vocabulary is used to do them. Yates, Orlikowski, & Okamura (1999![]() ) term genres as “socially recognized types of communicative actions . . . that are habitually enacted by members of a community to realize particular social purposes. A genre may be identified by its socially recognized purpose and shared characteristics of form.” Furthermore, Swales (1990

) term genres as “socially recognized types of communicative actions . . . that are habitually enacted by members of a community to realize particular social purposes. A genre may be identified by its socially recognized purpose and shared characteristics of form.” Furthermore, Swales (1990![]() ) stated that “A genre comprises a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse community and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This rationale shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constrains choice of content and style.”

) stated that “A genre comprises a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse community and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This rationale shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constrains choice of content and style.”

2.5. The GBA

In 2004 the GBA was introduced into the English curriculum in Indonesia. Although the curriculumwas changed from KTSP to the new version, K-13, genre is still a priority in teaching English in schools. In order to provide a coherent text, implementation of GBA is needed. Johns (2002![]() ) described GBA as a system for literacy education that places documents (i.e., more expansive than a sentence) as the cornerstone of teaching and syllabuses. Thus, application of the GBA is based on the SFL view that the use of any social language is a document and that all documents reflect those genres of context (Christie, 1992

) described GBA as a system for literacy education that places documents (i.e., more expansive than a sentence) as the cornerstone of teaching and syllabuses. Thus, application of the GBA is based on the SFL view that the use of any social language is a document and that all documents reflect those genres of context (Christie, 1992![]() ). The five key features of the GBA are described in Hyland (2007

). The five key features of the GBA are described in Hyland (2007![]() ). First, it involves identifiable pedagogy and how to assess it (Martin, 1999

). First, it involves identifiable pedagogy and how to assess it (Martin, 1999![]() ). Second, it draws on SFL to explain the importance of each linguistic option to the meaning and structure of the language in general. Third, engagement in the form of mutual knowledge, teaching as encouragement that allows students to improve their capacity to produce meaning throughout language exercises (Martin, 1999

). Second, it draws on SFL to explain the importance of each linguistic option to the meaning and structure of the language in general. Third, engagement in the form of mutual knowledge, teaching as encouragement that allows students to improve their capacity to produce meaning throughout language exercises (Martin, 1999![]() ). Fourth, teaching is an approach to enable students to access, appreciate, and question meaningful documents (Martin, 1999

). Fourth, teaching is an approach to enable students to access, appreciate, and question meaningful documents (Martin, 1999![]() ). Finally, GBA seeks to raise the understanding of students and teachers about how documents function. These main features of GBA are represented inteaching/studying phases.

). Finally, GBA seeks to raise the understanding of students and teachers about how documents function. These main features of GBA are represented inteaching/studying phases.

2.6. Stages of the Teaching Learning Cycle

This sequence is a text-based conceptual process that guides the student from the dependent to the independent development of understanding (Burns, 2010![]() ; Callaghan & Rothery, 1988

; Callaghan & Rothery, 1988![]() ). Feez (1998

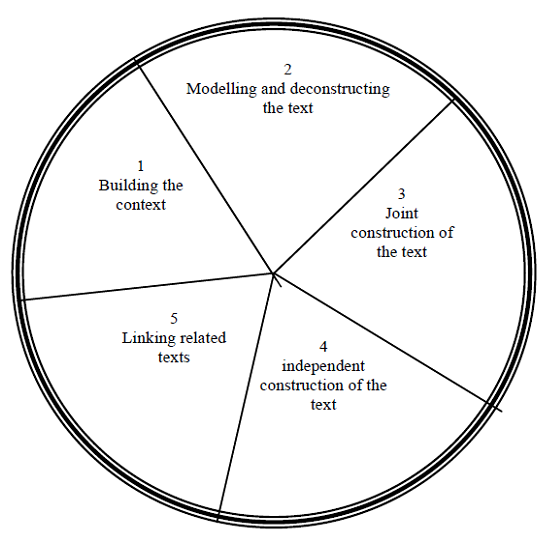

). Feez (1998![]() ) established that GBA phases span five stages: building context/building knowledge in the field (BKOF), modeling and deconstructing text (MOT), joint construction of the text (JCT), independent construction of the text (ICT), and linking relevant texts (LRT). The five phases are shown in Figure 1.

) established that GBA phases span five stages: building context/building knowledge in the field (BKOF), modeling and deconstructing text (MOT), joint construction of the text (JCT), independent construction of the text (ICT), and linking relevant texts (LRT). The five phases are shown in Figure 1.

Figure1. Phases of the teaching/study cycle.

Source: Feez (1998![]() ).

).

Following Feez (1998![]() ),the GBA has a different aim and focus at each phase of the teacing/study cycle, as eleborated in the following.

),the GBA has a different aim and focus at each phase of the teacing/study cycle, as eleborated in the following.

At the building the context stage

- Agenuine design of the genre/texttype being analyzed is first inserted into the social context.

- The student examines the immediate cultural context where the genre/texttype is used, and the social function of the genre/texttypes is accomplished.

- The student analyzes the current meaning of the scenario by analyzing the model text registry chosen, based on the goals of the course and the student's needs.

At the modelling and deconstructing the text stage, the students

- Analyze the systemic trends and language characteristics (linguistic realizations) of the text/genre design.

- Associate the design with several other text-type cases.

At the joint construction of the text stage

- The student continues to contribute to the creation of complete text-type examples.

- The instructor progressively decreases text-construction contribution as students come closer to managing the texttype individually.

At the independent construction of the text stage

- The student will compose separately to create documents.

- Student success will be used as the measurement of achievement.

At the linking to related texts stage, students analyze how they can relate to what they have learned throughout this teaching/study course:

- Other documents with identical sense.

- Future or previous instruction and learning phases.

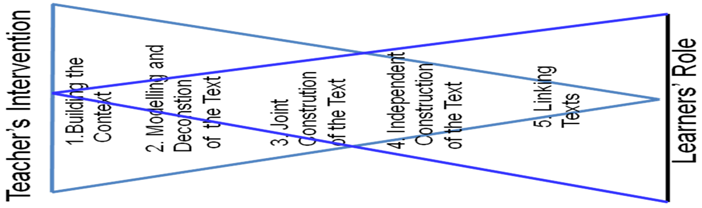

Every stage of the cycle above has different activities oriented in different purposes or focus. It is initiated by the dominant teacher intervention in the first stage and is less evident in the following stages, until no intervention (totally student intervention) occurs in the final stage. Figure 2 shows the activities of teacher and students.

Figure2. Teacher and student activity in the classroom.

Figure 2 shows that the teacher’s intervention is dominant in the first stage, building the context, and it becomes less and less influential in the following stages. The student’s role becomes more dominantin the fourth and fifth stages. Figure 2 is a development of Figure 1 in regard to the application of classroom activity.

2.7. Importance of Writing

Elashri (2013![]() ) claimed that writing as an art is of critical importance, for various reasons. The first explanation is that writing requires a lot more than the reproduction of speech. The second explanation for concentrating on writing is that it aims to connect, through a new design that students most easily explore and understand, expression and the written word. The third explanation is that writing is a better way than interpreting a written code. Another virtue of writing is that it is more than thinking in a different sense. While they say it first and then write it down, how students learn to write may first demonstrate that the two forms of speech are arranged according to different concepts. Writing is possibly a valuable way of improving one's comprehension of the subject about which one is writing. Thus, as per Elashri (2013

) claimed that writing as an art is of critical importance, for various reasons. The first explanation is that writing requires a lot more than the reproduction of speech. The second explanation for concentrating on writing is that it aims to connect, through a new design that students most easily explore and understand, expression and the written word. The third explanation is that writing is a better way than interpreting a written code. Another virtue of writing is that it is more than thinking in a different sense. While they say it first and then write it down, how students learn to write may first demonstrate that the two forms of speech are arranged according to different concepts. Writing is possibly a valuable way of improving one's comprehension of the subject about which one is writing. Thus, as per Elashri (2013![]() ), writing allows students to challenge one's perceptions of the claims of others, as well as one's perspectives and values, in order to contribute to the continuing dialog in a certain way that strengthens society's perception of the related field of knowledge.

), writing allows students to challenge one's perceptions of the claims of others, as well as one's perspectives and values, in order to contribute to the continuing dialog in a certain way that strengthens society's perception of the related field of knowledge.

3. Method

This study was conducted as a research study to facilitate further comprehensive exploration on issues concerning the implementation of the GBA in overcoming students’ difficulties in writing texts. This research used a descriptive quantitative method. Herman et al. (2020![]() ) stated that quantitative refers to describe variables, to examine relationships among variables, and to determine cause-and-effect interactions between variables It deals with the research method, which focuses on the result then the process. To determine the information and quality of the object under research, the researchers collected the data, made the measurements and the results of the data were then collected. To collect the data, three techniques were used: observation, document analysis (writing test), and interview.

) stated that quantitative refers to describe variables, to examine relationships among variables, and to determine cause-and-effect interactions between variables It deals with the research method, which focuses on the result then the process. To determine the information and quality of the object under research, the researchers collected the data, made the measurements and the results of the data were then collected. To collect the data, three techniques were used: observation, document analysis (writing test), and interview.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Implementation and Results

The data were acquired by conducting the GBA in the classroom. In the BKOF stage, the teacher led the students from their surroundings in order to present the subject and develop student history awareness while concentrating on content. At the MOT level, the students were faced with a variety of different descriptive texts. A sample of a document was given to the students in order to encourage them to explore its contents, schematic structure, and linguistic features. This process is in line with that suggested by Gibbons (2002![]() ): in the MOT stage, the teacher introduced the contents, schematic structure, and linguistic feature of the text. Hyland (2004

): in the MOT stage, the teacher introduced the contents, schematic structure, and linguistic feature of the text. Hyland (2004![]() ) suggested giving the students a task which required them to write a text in the JCOT stage. On this occasion, the teacher led a group discussion to compose a document. Students were allowed to collaborate as a team to combine all information (words) in the BKOF and MOT stages. This phase requires that students write a descriptive text on another topic. In the ICOT phase, students were allowed to compose a descriptive text independently using their own style (free subject). This was done to enhance their writing of text. Hence, before constructing the text, the teacher explained and provided a model descriptive text in order to remind the students of what had been discussed in the previous stage (covering schematic structure, linguistic feature, and content). Then, in the last stage, LRT, the students were asked to investigate or summarize what they had learned. This activity is the most difficult process because the students require encouragement.

) suggested giving the students a task which required them to write a text in the JCOT stage. On this occasion, the teacher led a group discussion to compose a document. Students were allowed to collaborate as a team to combine all information (words) in the BKOF and MOT stages. This phase requires that students write a descriptive text on another topic. In the ICOT phase, students were allowed to compose a descriptive text independently using their own style (free subject). This was done to enhance their writing of text. Hence, before constructing the text, the teacher explained and provided a model descriptive text in order to remind the students of what had been discussed in the previous stage (covering schematic structure, linguistic feature, and content). Then, in the last stage, LRT, the students were asked to investigate or summarize what they had learned. This activity is the most difficult process because the students require encouragement.

After analyzing the data, the research findings showed that students might be aided in their writing using the GBA. Any discrepancies or changes in the entire student population were also checked from the outcome post-test of control to experiment group is 881 or 41,95 point in average.

Below are details of the results.

4.1.1.Results of Descriptive Analysis

Table1.Results of mean summary

| Pretest | Mean | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean summary | |

| 43.4 | 44.55 | 37.24 | 43 | 42 | 41.51 | 41.95 | |

| Mean | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean summary | |

| 75.76 | 78.95 | 80.51 | 80.23 | 78.67 | 80.36 | 79.08 | |

Source: Data analysis from July 30, 2020 SPSS –X VERSION 24.

Based on the outcome of the mean summary, it can be inferred that the mean summary of post-test was greater than the actual mean pretest summary (79.08 > 41.95).

Table2. Descriptive analysis of pre- and post-test

| Test | Mean |

Standard deviation |

Median |

Max. score |

Min. score |

Variance |

| Pretest | 41.95 |

3.783 |

45.16 |

51.49 |

37.18 |

14.77 |

| Post-test | 79.08 |

14.587 |

78.73 |

82 |

75.55 |

4.558 |

Source: Data analysis from July 30, 2020 SPSS –X VERSION 24.

The post-test instrument was superior to the pretest in each descriptive analysis. A t-test was performed to determine any substantial gap between pre- and post-test mean score. Data distribution was evaluated prior to the t-test. The method used for the t-test was then selected. If the data were normally distributed a parametric test was evaluated, but if not a nonparametric test is used. Data were defined as typical if the significance of the Kolgomorov–Smirnov value was >0.05. The outcome of normality testing is summarized in Table 3.

4.1.2.Results of Normality Test.

Table3.Results of normality test.

| Test of normality | |||

Kolmogorov–Smirnovª |

|||

Statistic |

Df |

Sig. |

|

| Summary mean pretest | 0.174 |

21 |

0.097 |

| Summary mean post-test | 0.120 |

21 |

0.200 |

As a conclusion of the normality test, as seen in Table 3, the Kolgomorov–Smirnov value for the pre- and post-test was0.097 and 0.200, respectively. When the significance in both pre- and post-test was>0.05, the data were classified as normally distributed. Therefore, paired t-test sampling was performed.

Based on the results of the implementation of the GBA above, the results show that use of the GBA enables the student to compose text. The researchers used a sample, descriptive text in applying GBA, after which they found there were certain aspects that needed to be improved such as building context (covers brainstorming) and the social purpose of descriptive text, students’ eagerness to learn English (active in class), generating the ideas or topics of descriptive text, developing part descriptions of descriptive text, enhancing their vocabulary, and developing their motivation to write descriptive text.

4.2. Discussion

The above findings indicate that use of the GBA has been found to support students with problems in writing. On this occasion, the researcher would like to address the students’ writing. Most students felt more inspired to compose a document, but several made errors in their use of tense, such as “wants” rather than “wanted”. However, this sort of grammatical error will affect the quality of writing because it breaks the rules of English grammar and writing. Nevertheless, at least the use of GBA could improve students’ motivation to write text and also enhance their vocabulary.

5. Conclusion

After presenting a summary of the GBA and reviewing it in the form of descriptive writing, the researchers found that is use represents a potential solution and new approach to teaching English as a foreign language. Moreover, improvements were noted after implementation of the GBA in writing, such as building the context (covers brainstorming) and social purposes of descriptive text, students’ eagerness to learn English (active in class), generating the ideas or topics of descriptive text, developing the part description of descriptive text, enhancing students’ vocabulary, and developing students’ motivation to write descriptive text.

Here, the researchers suggest that GBA be recommended as a new concept in the efficient teaching and learning of English, especially in writing. Moreover, the researchers hope that other workers in this field will conduct more research relating to the GBA in other fields.

Citation| Herman; Ridwin Purba; Nguyen Van Thao; Anita Purba (2020). Using Genre-based Approach to Overcome Students’ Difficulties in Writing. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(4): 464-470. |

References

Bhatia, V. K. (1991). A genre-based approach to ESP materials. World Englishes, 10(2), 153-166.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971x.1991.tb00148.x .

Bradford-Watts, K. (2003). What is genre and why is it useful for language teachers? Language Teacher-Kyoto-Jalt, 27(5), 6-8.

Burns, A. (2010). Teaching speaking using genre-based pedagogy. In M. Olafsson (Ed.), Symposium 2009. Genrer och funktionellt språk i teori och praktik (pp. 230-246). Stockholm: National Centre for Swedish as a Second Language, University of Stockholm.

Butt, D., Fahey, R., Feeze, S., Spinks, S., & Yallop, C. (2000). Using functional grammar: An explorer’s guide (2nd ed.). Sydney: Macquarie University.

Callaghan, M., & Rothery, J. (1988). Teaching factual writing: a genre-based approach. Sydney: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged Schools Program.

Christie, F. (1992). Literacy in Australia. In W. Grabe, et al. (eds.). Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 12. Literacy (pp. 142-155). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Droga, L., & Humphrey, S. (2002). Getting started with functional grammar. Berry: Target Texts.

Dudley-Evans, T. (1987). Genre analysis and ESP: ELR Journal 1. University of Binningham: English Language Research, 1, 27-39.

Elashri, I. I. E. A.-E. (2013). The effect of the genre-based approach to teaching writing on the EFL Al-Azhr secondary students' writing skills and their attitudes towards writing. Mansoura University: Faculty of Education Department of Methods and Curriculum.

Feez, S. (1998). Text-based syllabus design. Sydney: NCELTR Macquarie University.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language scaffolding learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1985). An introduction to functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Herman. (2014). An experiential function on students’ Genre of writing. Jakarta: Halaman Moeka Publishing.

Herman, Sibarani, J. K., & Pardede, H. (2020). The effect of Jigsaw technique in reading comprehension on Recount text. Cetta: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan, 3(1), 84-102.

Hopkins, A., & Dudley-Evans, A. (1988). A genre-based investigations of the discussions sections in articles and dissertation. English for Specific Purposes, 7(2), 113-122.

Hyland, K. (1992). Genre analysis: Just another fad? Forum, 30(2), 14-17.

Hyland, K. (2003). Genre-based pedagogies: A social response to process. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(1), 17-29.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1060-3743(02)00124-8 .

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(3), 148-164.

Johns, A. M. (2002). Genre in the classroom: Multiple perspectives. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum.

Martin, J. R. (1985). Process and text: Two aspects of semiosis”, in Benson, J. and Greaves, W. (Eds), Systemic Perspectives on Discourse. Paper presented at the Selected Theoretical Papers from the 9th International Systemic Workshop, Ablex, Norwood, NJ.

Martin, J. R. (1999). Mentoring semogenesis: ‘Genre-based’literacy pedagogy. In F. Christie (Ed.), Pedagogy and the shaping of consciousness (pp. 123-155). London; New York: Continuum.

Martin, J. R. (1992). English text: System and structures. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Pardede, H., & Herman, H. (2020). The effect of numbered heads together method to the students’ ability in writing recount text. Cetta: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan, 3(2), 291-303.

Permana, D. T., Zuhri, F., & Fauris, Z. (2013). The implementation of picture series as media in teaching writing of a narrative text of the tenth graders of senior high school. Surabaya: State University of Surabaya.

Rajagukguk, T. A., Herman, & Sihombing, P. R. S. (2020). The effect of using collaborative writing method on students’ writing recount text at grade ten of SMK YP 1 HKBP Pematangsiantar. Acitya: Journal of Teaching & Education, 2(2), 95-114.

Richards, J. C., Platt, J., & Platt, H. (1993). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. New York: Longman.

Robinson, P. (1991). ESP today: A practitioner’s guide. UK: Prentice Hall International (UK) Ltd. Prentice Hall.

Sinaga, H., Herman, & Pasaribu, E. (2020). The effect of anagram game on students’ vocabulary achievement at grade eight of SMP Negeri 8 Pematangsiantar. Journal of English Educational Study, 3(1), 51-60.

Sinaga, H., Herman, & Hutauruk, B. S. (2020). Students’ difficulties in using personal pronouns in writing recount text. Scientia: Jurnal Hasil Penelitian, 5(1), 29-36.Available at: https://doi.org/10.32923/sci.v5i1.1341 .

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis – english in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yates, J., Orlikowski, W. J., & Okamura, K. (1999). Explicit and implicit structuring of genres in electronic communication: reinforcement and change in social interaction. Organization Science, 10(1), 83-117.

Yuliani, I. P. (2012). The implementation of genre-based approach to teaching narrative writing. Paper presented at the Organizing of the 39th International Systemic Functional Congress. Sydney.

| Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |