Talent Management in Higher Education Institutions: Developing Leadership Competencies

1,2Centre of Leadership Profiling, Akademi Kepimpinan Pendidikan Tinggi, Malaysia.

3Faculty of Accountancy, Universiti Teknologi MARA Selangor, Malaysia.

Abstract

This paper presents the development process of talent management in higher education institutions. Specifically, this study aims to identify clusters that best fit the leadership competency framework for those institutions. This study utilizes the qualitative approach via focus group discussion with the Leadership Competency and Instrument Committee in AKEPT, and also by interviews with academics in the public universities. The findings from the focus group discussion and interview demonstrate five clusters of leadership competency skills framework: personnel effectiveness, cognition, leading, impact and influence, and achievement and action. Within these clusters, issues were identified that need to be taken into consideration when selecting future leaders in higher education institutions. Based on the findings, a set of attributes were listed that can be adopted in the future to allow leaders of higher institutional education to enhance their sustainability performance. This paper provides an understanding to interested parties on the attributes of good leaders for higher education institutions.

Keywords:Academics, Leadership, Talent management, Higher education, Malaysia.

Contribution of this paper to the literature: This paper provides a competency leadership skills framework in identifying potential good leaders in higher education institutions.

1. Introduction

Leadership is considered a crucial factor and is increasingly demanding change, choice, flexibility, and variety in organizations (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014![]() ; Ghani. & Mohamed Jais, 2018

; Ghani. & Mohamed Jais, 2018![]() ; Mohamed, Yahaya, & Ghani, 2020

; Mohamed, Yahaya, & Ghani, 2020![]() ) . Perhaps the earliest concept on leadership was initiated by Burns (1978

) . Perhaps the earliest concept on leadership was initiated by Burns (1978![]() ), who defined a true leader as one who can induce followers to act in accordance with the motivations of both leaders and followers. Burns further noted that both leaders and followers engage in a common enterprise without which it would become meaningless. Since Burns’ study, the issue of leadership has long been debated due to its importance in an organization and being considered a crucial factor. Bechtel, 2010

), who defined a true leader as one who can induce followers to act in accordance with the motivations of both leaders and followers. Burns further noted that both leaders and followers engage in a common enterprise without which it would become meaningless. Since Burns’ study, the issue of leadership has long been debated due to its importance in an organization and being considered a crucial factor. Bechtel, 2010![]() ) suggesting delayering of organizations and empowerment of individual employees and that the future for both individual and organization lies not in promotion to successively higher levels of management, but on the value development of the individual as a leader (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014

) suggesting delayering of organizations and empowerment of individual employees and that the future for both individual and organization lies not in promotion to successively higher levels of management, but on the value development of the individual as a leader (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014![]() ; Northouse, 2018

; Northouse, 2018![]() ). However, other studies have argued that leadership in the higher education is not similar to other organizations since it represents a unique set of leadership challenges (Anderson, 2015

). However, other studies have argued that leadership in the higher education is not similar to other organizations since it represents a unique set of leadership challenges (Anderson, 2015![]() ; Ruben & Gigliotti, 2017

; Ruben & Gigliotti, 2017![]() ).

).

One of the challenges is that higher education institutions are perceived to be assuming a role in adapting and redirecting actions to promote sustainable development, regarding their education system and top management teams, professors, and researchers as sustainable leaders (Ruben & Gigliotti, 2017![]() ). Higher education institutions are also perceived to encourage the development and education of tomorrow’s leaders, who will eventually hold important positions in various organizations (Filho et al., 2020

). Higher education institutions are also perceived to encourage the development and education of tomorrow’s leaders, who will eventually hold important positions in various organizations (Filho et al., 2020![]() ). Leadership in higher education institutions is often related to individual skills in guiding their peers and subordinates and taking actions to achieve effective and efficient organization. To have such skills, one must possess leadership competencies.

). Leadership in higher education institutions is often related to individual skills in guiding their peers and subordinates and taking actions to achieve effective and efficient organization. To have such skills, one must possess leadership competencies.

A group of studies in the literature of leadership have attempted to identify leadership competencies in organizations (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014![]() ; Gigliotti, Ruben, & Goldthwaite, 2017

; Gigliotti, Ruben, & Goldthwaite, 2017![]() ; Ruben. & Gigliotti, 2019

; Ruben. & Gigliotti, 2019![]() ) . Most of these studies suggested that there are two perspectives of leadership development, namely the individual and the organizational. The individual perspective in leadership development involves the activities and experiences that would increase job-related skills and knowledge and, subsequently, offers opportunities for employees to change and transform their organization (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014

) . Most of these studies suggested that there are two perspectives of leadership development, namely the individual and the organizational. The individual perspective in leadership development involves the activities and experiences that would increase job-related skills and knowledge and, subsequently, offers opportunities for employees to change and transform their organization (Chouhan & Srivastava, 2014![]() ; Ruben. & Gigliotti, 2019

; Ruben. & Gigliotti, 2019![]() ). In the organizational perspective on the other hand, leadership development involves personal and professional growth that allows employees to sustain, grow, and transform organizations (Katsinas & Kempner, 2005

). In the organizational perspective on the other hand, leadership development involves personal and professional growth that allows employees to sustain, grow, and transform organizations (Katsinas & Kempner, 2005![]() ). However, these studies were mostly conducted in a non-higher education institution literature, leaving empirical examination of leadership competencies in higher education institutions largely unexplored. One may then pose the question: what exactly are the leadership competencies in higher educational institutions?

). However, these studies were mostly conducted in a non-higher education institution literature, leaving empirical examination of leadership competencies in higher education institutions largely unexplored. One may then pose the question: what exactly are the leadership competencies in higher educational institutions?

This study aims to examine leadership competencies in higher education institutions. Using Akademi Kepimpinan Pendidikan Tinggi (AKEPT), a small unit under the Ministry of Higher Education in Malaysia as the setting, this paper explores the concept of leadership in higher education institutions and, subsequently, identifies leadership competencies using a qualitative approach. This study provides an understanding on the leadership competency framework in achieving organizational outcomes. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of relevant literature while Section 3 outlines the modeling methodology. The framework is presented in Section 4 and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Burns (1978![]() ) defined leadership as “one of the most observed and least understood phenomena on earth. Leadership is indeed a dynamic undertaking that both researchers and practitioners have struggled to make sense of for centuries”. Kouzes & Posner (2002

) defined leadership as “one of the most observed and least understood phenomena on earth. Leadership is indeed a dynamic undertaking that both researchers and practitioners have struggled to make sense of for centuries”. Kouzes & Posner (2002![]() ), authors of the widely read book The Leadership Challenge, define leadership as “a relationship between those who aspire to lead and those who choose to follow” (2002, p. 20). In their Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership for the National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs, Dugan & Komives (2007

), authors of the widely read book The Leadership Challenge, define leadership as “a relationship between those who aspire to lead and those who choose to follow” (2002, p. 20). In their Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership for the National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs, Dugan & Komives (2007![]() ) define leadership as “a relational, transformative, process oriented, learned, and change-directed phenomenon” (2007, p. 9). To help establish a clear philosophy, the Leadership Development Institute will adopt the view that leadership is a relationship between leaders and followers in accomplishing positive change. Therefore, identifying the competencies of a leader is imperative.

) define leadership as “a relational, transformative, process oriented, learned, and change-directed phenomenon” (2007, p. 9). To help establish a clear philosophy, the Leadership Development Institute will adopt the view that leadership is a relationship between leaders and followers in accomplishing positive change. Therefore, identifying the competencies of a leader is imperative.

Leadership competencies refer to the knowledge, skills, behaviors, and attributes that are important for good leadership (Smith & Wolverton, 2010![]() ). They comprise key characteristics that leaders must have in order to achieve desirable organization outcomes (Ruben & Gigliotti, 2019

). They comprise key characteristics that leaders must have in order to achieve desirable organization outcomes (Ruben & Gigliotti, 2019![]() ; Tichy, 1997

; Tichy, 1997![]() ; Wallin, 2009

; Wallin, 2009![]() ; Yukl, 2002

; Yukl, 2002![]() ) . Leadership competencies associate with the skills of a leader that contribute to superior performance, through which organizations can better identify and develop their next generation of leaders (R. N. S. Mohamad & Abdullah, 2017

) . Leadership competencies associate with the skills of a leader that contribute to superior performance, through which organizations can better identify and develop their next generation of leaders (R. N. S. Mohamad & Abdullah, 2017![]() ). Studies that have examined leadership competencies often examined their abilities in terms of traits, behaviors, transactions, power, influence, situations, and transformational abilities (Bass, 1998

). Studies that have examined leadership competencies often examined their abilities in terms of traits, behaviors, transactions, power, influence, situations, and transformational abilities (Bass, 1998![]() ; Bensimon, Neumann, & Birnbaum, 1989

; Bensimon, Neumann, & Birnbaum, 1989![]() ; Yukl, 2002

; Yukl, 2002![]() ). These studies often argued that leadership competencies are critical to success in various positions within an organization. McClelland (1973

). These studies often argued that leadership competencies are critical to success in various positions within an organization. McClelland (1973![]() ) posited that in measuring competencies, aptitude and intelligence are not sufficient as predictors of successful performance; rather, one must also take into consideration clusters of life outcomes, namely occupational outcomes and social ones such as leadership and interpersonal skills.

) posited that in measuring competencies, aptitude and intelligence are not sufficient as predictors of successful performance; rather, one must also take into consideration clusters of life outcomes, namely occupational outcomes and social ones such as leadership and interpersonal skills.

Over several decades, the issue of leadership has long been debated due to its importance in an organization because leadership is considered one of the most observed but least understood phenomena involving dynamic undertaking; both researchers and practitioners have struggled to make sense of this for centuries (Burns, 1978![]() ; Ghani. & Mohamed Jais, 2018

; Ghani. & Mohamed Jais, 2018![]() ; Mohamed et al., 2020

; Mohamed et al., 2020![]() ). A large body of leadership literature has examined the issue of leadership and subsequently derived multiple contexts and frameworks (Bass, 1998

). A large body of leadership literature has examined the issue of leadership and subsequently derived multiple contexts and frameworks (Bass, 1998![]() ; Bechtel, 2010

; Bechtel, 2010![]() ). These studies examined leaders and their leadership abilities in terms of behaviors, situations, and transformational abilities (Bechtel, 2010

). These studies examined leaders and their leadership abilities in terms of behaviors, situations, and transformational abilities (Bechtel, 2010![]() ; Burns, 1978

; Burns, 1978![]() ; Yukl, 2002

; Yukl, 2002![]() ). Most of these studies suggested that leadership is defined as a competent leader, regardless of the type of organization. However, other studies have suggested that leadership in higher education institutions is different because these present a unique set of leadership challenges (Anderson, 2015

). Most of these studies suggested that leadership is defined as a competent leader, regardless of the type of organization. However, other studies have suggested that leadership in higher education institutions is different because these present a unique set of leadership challenges (Anderson, 2015![]() ; Smith & Wolverton, 2010

; Smith & Wolverton, 2010![]() ). Smith & Wolverton (2010

). Smith & Wolverton (2010![]() ) argued that the members of a higher education institution are often operating in an environment that has little supervision but has a powerful voice in significant institutional decisions. Therefore, leaders in higher educational institutions would need to retain a balance in the interests of their faculties and departments, as well as in the interests of other stakeholders such as students and the government. Arguably, the definition of leadership may not be relevant to leadership in higher education institutions.

) argued that the members of a higher education institution are often operating in an environment that has little supervision but has a powerful voice in significant institutional decisions. Therefore, leaders in higher educational institutions would need to retain a balance in the interests of their faculties and departments, as well as in the interests of other stakeholders such as students and the government. Arguably, the definition of leadership may not be relevant to leadership in higher education institutions.

Filan & Seagren (2003![]() ) opined that higher education leadership can be seen as dynamic, complex and multidimensional and thus offers numerous opportunities for further investigation. “due to its constants change, adjustments and turbulent environment in the last decade”. The members of a higher education institution are often operating in an environment that has little supervision and, yet, have a powerful voice in significant institutional decisions. Leaders need to have a balance in the interests of the faculties and departments, as well as the interests of other stakeholders. This is consistent with Taylor (2005

) opined that higher education leadership can be seen as dynamic, complex and multidimensional and thus offers numerous opportunities for further investigation. “due to its constants change, adjustments and turbulent environment in the last decade”. The members of a higher education institution are often operating in an environment that has little supervision and, yet, have a powerful voice in significant institutional decisions. Leaders need to have a balance in the interests of the faculties and departments, as well as the interests of other stakeholders. This is consistent with Taylor (2005![]() ), who found that effective leadership in the academic context is a synergy among variable characteristics of the individual, development strategies, academic development roles and institutional context and determined successful practice and leadership in institutions. Thus, there is a need to identify potential leaders who possess not only academic leadership but also institutional leadership.

), who found that effective leadership in the academic context is a synergy among variable characteristics of the individual, development strategies, academic development roles and institutional context and determined successful practice and leadership in institutions. Thus, there is a need to identify potential leaders who possess not only academic leadership but also institutional leadership.

Academic leadership refers to scholars who are influential experts in their respective fields and engage in impactful pursuits (Radwan., Ghavifekr, & Abdul Razak, 2020![]() ). Academic leaders display the utmost integrity in pursuing science and scholarship, whether in advancing novel theories and ideas, leading methodological or pedagogical innovation, or spearheading meaningful societal engagement. It encompasses being an exemplar of teaching and learning, research, or professional practice while also mentoring others to achieve academic excellence (Radwan, Razak, & Ghavifekr, 2020

). Academic leaders display the utmost integrity in pursuing science and scholarship, whether in advancing novel theories and ideas, leading methodological or pedagogical innovation, or spearheading meaningful societal engagement. It encompasses being an exemplar of teaching and learning, research, or professional practice while also mentoring others to achieve academic excellence (Radwan, Razak, & Ghavifekr, 2020![]() ). One of the aspirations of the Differentiated Career Pathways (DCP) under the New Academia Talent Management (NATF) is for every academic to eventually grow into an academic leader in his or her chosen field or career pathway.

). One of the aspirations of the Differentiated Career Pathways (DCP) under the New Academia Talent Management (NATF) is for every academic to eventually grow into an academic leader in his or her chosen field or career pathway.

Institutional leadership on the other hand, refers to top and middle management in the university who perform management functions and inspire to realizing the university’s vision and mission (Filho et al., 2020![]() ). They demonstrate managerial capabilities by being flexible, adaptable, strategic and, most of all, effective. In addition to being scholars in their own right, they are able to inspire others by creating, supporting, and sustaining environments for talent to flourish. They have vision and foresight, and are able to balance idealism and realism through optimism and pragmatism. Institutional leaders combine their strategic and managerial talents with holistic human values to promote well-being among students, staff, community, the nation, and humanity (S. I. S. Mohamad, Muhammad, Hussin, & Habidin, 2017

). They demonstrate managerial capabilities by being flexible, adaptable, strategic and, most of all, effective. In addition to being scholars in their own right, they are able to inspire others by creating, supporting, and sustaining environments for talent to flourish. They have vision and foresight, and are able to balance idealism and realism through optimism and pragmatism. Institutional leaders combine their strategic and managerial talents with holistic human values to promote well-being among students, staff, community, the nation, and humanity (S. I. S. Mohamad, Muhammad, Hussin, & Habidin, 2017![]() ). In the university setting, institutional leadership positions have always been considered temporary appointments for a stipulated period of time.

). In the university setting, institutional leadership positions have always been considered temporary appointments for a stipulated period of time.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The Setting and Participants

AKEPT is chosen as the setting in this case study. Since 2015, AKEPT has been actively involved in Leadership Talent Management for Higher Education Institutions in Malaysia. It is aligned with the aspiration of Malaysia Education Blueprint (Higher Education) 2015–2025, which clearly states the need to create competent leaders aspiring towards talent excellence and, as such, this initiative can gauge the leadership competency framework for effective and efficient talent management.

This study relied on the AKEPT Leadership Competency and Instrument Committee. This committee was formed to develop generic leadership competency for higher education institutions in Malaysia. Individuals from the AKEPT Leadership Competency and Instrument Committee, which consists of experts from various fields, have vast experience in leadership and hence are deemed suitable for this study to conduct focus group discussions. There were 12 committee members and, during focus group discussion, focus groups were encouraged to discuss their ideas on the best leadership competency themes in developing a leadership competency framework.

Individuals, comprising academics identified as potential leaders from universities and polytechnics, were approached. These academics were identified through the AKEPT Leadership Assessment Centre. Four hundred and ninety-four academics were approached based on psychometric testing, Behavioral Event Interview (BEI) and Strategic Plan Presentation (SPP) approaches. In total, ten individuals were approached to ensure consistency of the findings in the focus group discussion and individual interviews.

3.2. Research Instrument and Data Collection

This study utilized focus group discussion to extract a more in-depth view of the leadership competency framework from the viewpoint of the committee. The questions were developed based on adaptation from Spencer & Spencer (1993![]() ), with some modifications to suit the context of AKEPT. The issues discussed in the focus group within the committee included the cluster type that needs to be included in the leadership competency framework, the appropriate competency themes, the placement of competency themes in clusters, and determining the suitability of competency themes in gauging potential leaders in the highest education institutions.

), with some modifications to suit the context of AKEPT. The issues discussed in the focus group within the committee included the cluster type that needs to be included in the leadership competency framework, the appropriate competency themes, the placement of competency themes in clusters, and determining the suitability of competency themes in gauging potential leaders in the highest education institutions.

The focus group discussions were conducted over a period of 3 years, with each session being conducted with the committee members on four occasions. Upon completion of the focus group discussion, qualitative data were then coded and categorized to identify the competency theme variables that could be included as part of the leadership competency framework. Subsequently academics previously identified as potential leaders from universities and polytechnics were approached after identification of competency themes and clusters. These individuals were also contacted via email or telephone requesting an interview. Upon obtaining their consent, individual interviews were conducted at separate sessions to determine whether the proposed competency theme and clusters for identifying potential talents represent the leadership competency framework for higher education institutions.

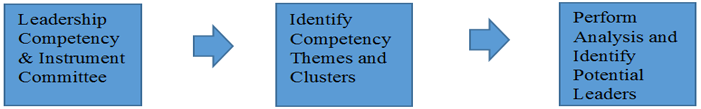

3.3. The Model

Figure 1 presents the model for analyzing the leadership competency framework for higher education institutions in Malaysia. To further enhance the credibility of the proposed components, this study also reviewed documents as part of the data collection (Tellis, 1997![]() ). The documents include responses from 494 academics from 20 public universities, polytechnics, and other related higher education agencies that had been profiled through the AKEPT Leadership Assessment Centre. Three approaches – psychometric test, BEI, and SPP – were used to assess potential leaders. This is consistent with Ghani, Muhammad, & Said (2012

). The documents include responses from 494 academics from 20 public universities, polytechnics, and other related higher education agencies that had been profiled through the AKEPT Leadership Assessment Centre. Three approaches – psychometric test, BEI, and SPP – were used to assess potential leaders. This is consistent with Ghani, Muhammad, & Said (2012![]() ), who adapted the Soft System Methodology developed by Checkland (1981

), who adapted the Soft System Methodology developed by Checkland (1981![]() ). In addition, this study also used the 2006 Pekeliling Perkhidmatan Bilangan 3 and the Malaysia Education Blueprint (Higher Education 2015–2025). The competency themes were then conceptualized and overall conclusions were made to represent the leadership competency framework.

). In addition, this study also used the 2006 Pekeliling Perkhidmatan Bilangan 3 and the Malaysia Education Blueprint (Higher Education 2015–2025). The competency themes were then conceptualized and overall conclusions were made to represent the leadership competency framework.

Figure 1. Model used in this study.

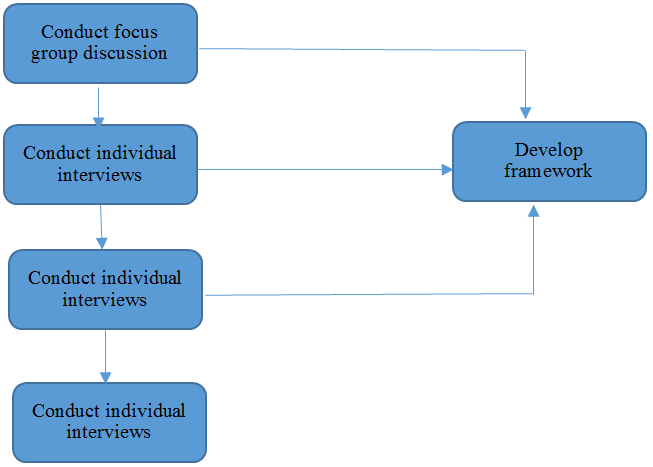

Figure 2 presents the research operational framework adapted from Alias and Abdul Rahman (2003![]() ), with some modifications.

), with some modifications.

Figure 2. Research operational framework.

4. Findings

Realizing that the aspirations of the Malaysian government in regard to higher education institutions influence the conceptualization of leadership competency themes, AKEPT developed the higher education leadership competency framework based on findings from focus group discussions and individual interviews. Based on focus group discussions, AKEPT found that these were in agreement that, in identifying competent potential leaders, there needs to be evaluation based on two components: from the individual level and from the institutional level. In view of this, AKEPT have provided two main components of higher education leadership – academic leadership and institutional leadership. This is consistent with Filan & Seagren (2003![]() ), who opined that leaders in higher education institutions must strike a balance in the interests of the faculties and departments, as well as in the interests of other stakeholders as a whole.

), who opined that leaders in higher education institutions must strike a balance in the interests of the faculties and departments, as well as in the interests of other stakeholders as a whole.

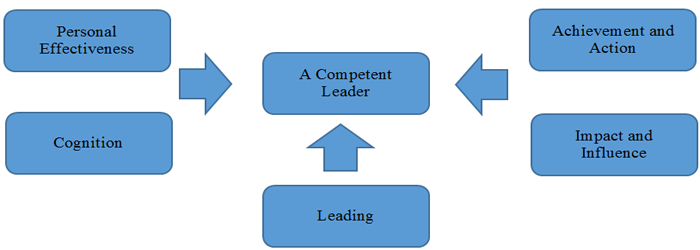

Based on these findings, AKEPT have identified that the higher education leadership competency framework consists of five main clusters: personnel effectiveness, cognition, leading, impact and influence. and achievement and action. Figure 3 depicts the higher education leadership competency framework in Malaysia developed by AKEPT.

Figure 3. Higher education leadership competency framework.

Within each cluster, possible issues are identified. The issues for each cluster are now presented.

4.1. Personnel Effectiveness

Within this cluster, four issues have been identified to determine whether a leader in the higher education institution is competent. Table 1 presents the issues regarding personal effectiveness.

Table 1. Issues regarding personal effectiveness.

| Cluster | Competency |

| Personal effectiveness | Self-confidence |

| Empathy | |

| Organizational commitment | |

| Values and ethics |

Issue 1: Self-confidence.A good leader must possess self-confidence because this forms an essential trait in leadership that involves influencing others (Axelrod, 2017![]() ) . AKEPT needs to assess this trait by looking at how the leader addresses his or her self-doubt, how the leader eliminates negative triggers and how the leader bounces back from his or her mistakes. The leader plays a role in psychological empowerment and goal setting (Kirkpatick & Locke, 1991

) . AKEPT needs to assess this trait by looking at how the leader addresses his or her self-doubt, how the leader eliminates negative triggers and how the leader bounces back from his or her mistakes. The leader plays a role in psychological empowerment and goal setting (Kirkpatick & Locke, 1991![]() ) toward his subordinates.

) toward his subordinates.

Issue 2: Empathy.A good leader must have empathy to inspire understanding and knowledge of their staff (Bass, 1998![]() ). He or she has the ability to put himself or herself in their staff’s shoes and imagine what they are going through in any situation. The leader has empathy to inspire understanding and knowledge of his staff and the ability to put him- or herself in their staff’s shoes (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008

). He or she has the ability to put himself or herself in their staff’s shoes and imagine what they are going through in any situation. The leader has empathy to inspire understanding and knowledge of his staff and the ability to put him- or herself in their staff’s shoes (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008![]() ).

).

Issue 3: Organizational commitment.The leader has the desire to belong to an organization and willingness to make extra effort for the benefit of that organization (Dirzyte, Patapas, Smalskys, & Udaviciute, 2013![]() ; Luthans, 2012

; Luthans, 2012![]() ). AKEPT needs to assess the strength of the leader’s organizational commitment towards their higher education institution, such as the level of attachment to that organization, his or her willingness to work on behalf of the organization, and also the likelihood of remaining a member of his or her higher educational institution.

). AKEPT needs to assess the strength of the leader’s organizational commitment towards their higher education institution, such as the level of attachment to that organization, his or her willingness to work on behalf of the organization, and also the likelihood of remaining a member of his or her higher educational institution.

Issue 4: Values and ethics. The leader must know what he or she values and recognizes the importance of ethical behavior, showing both values and ethics to their staff in creating trust by ‘walk the talk’ to demonstrate why the employees can trust him/her (Ghani et al., 2012![]() ). The values and ethics of leadership reflect these complexities and present many challenges for those who want to do the right thing (Neubert, Carlson, Kacmar, Roberts, & Chonko, 2009

). The values and ethics of leadership reflect these complexities and present many challenges for those who want to do the right thing (Neubert, Carlson, Kacmar, Roberts, & Chonko, 2009![]() ).

).

4.2. Cognition

Table 2 presents the issues raised by the focus group discussion in relation to cognition. Four issues have been raised within this cluster.

Table 2. Issues regarding cognition.

| Cluster | Competency |

| Personal effectiveness | Conceptual thinking |

| Analytical thinking | |

| Decision-making ability | |

| Planning and organizing |

Issue 1: Conceptual thinking. The leader has the ability to think conceptually (Peachey, Zhou, Damon, & Burton, 2015![]() ), to look at the overall picture and analyze hypothetical situations or concepts in order to compile insights. The leader’s cognitive capacity to understand and respond to a situation is important, including making sense of the moral and ethical dilemmas that may arise (Batliwala, 2010

), to look at the overall picture and analyze hypothetical situations or concepts in order to compile insights. The leader’s cognitive capacity to understand and respond to a situation is important, including making sense of the moral and ethical dilemmas that may arise (Batliwala, 2010![]() ).

).

Issue 2: Analytical thinking. The leader possesses analytical skills in terms of asking and answering questions, defining terms, identifying assumptions, interpreting and explaining, reasoning verbally, and uncertainty (Lai, 2011![]() ). The leader has the ability to analyze arguments, making inferences using inductive or deductive reasoning, judging and making decisions on solving problems (Willingham, 2007

). The leader has the ability to analyze arguments, making inferences using inductive or deductive reasoning, judging and making decisions on solving problems (Willingham, 2007![]() ).

).

Issue 3: Decision-making ability. AKEPT has to assess the leader in regard to their sense of urgency in terms of making timely decisions, and using intuition as well as data in the face of ambiguity. The leader needs to take follow-up actions to support decisions and be willing to stand by controversial decisions that can benefit their higher education institution (Lucena & Popadiuk, 2020![]() ).

).

Issue 4: Planning and organizing.The leader has the ability to accurately scope and secure the resources needed to accomplish projects, and also manages time and resources effectively, prioritizing efforts according to organizational goals (Grol & Wensing, 2013![]() ). AKEPT also must access whether the leader provides contingency plans by proactively developing those for unforeseen circumstances.

). AKEPT also must access whether the leader provides contingency plans by proactively developing those for unforeseen circumstances.

4.3. Leading

Within this cluster, three issues have been identified to determine whether a leader in a higher education institution is competent. Table 3 presents the relevant issues.

Table 3. Issues regarding leading.

| Cluster | Competency |

| Leading | Teamwork and team leadership |

| Leveraging diversity | |

| Changing leadership/adaptability |

Issue 1: Teamwork and team leadership.AKEPT must access whether the leader can delegate tasks to the appropriate individuals or group and, subsequently, promote collaboration among the team members and encourage others to cooperate and coordinate their efforts. The leader can manage conflicts by creating models and encouraging others to manage conflict openly and productively. The leader can also lead team meetings and prioritize team morale and productivity (Rosen & Callaly, 2005![]() ).

).

Issue 2: Leveraging diversity. A leader must know how to bring people from diverse workforces and backgrounds into his organization, because diversity promotes competition for the best talent, effectively increasing a diverse customer base (Jayne & Dipboye, 2004![]() ). This is because diversity promotes competition for the best talents, effectively increasing a diverse customer base leading to an increased market share and freeing up creativity, innovation, and improved group problem solving (Jayne & Dipboye, 2004

). This is because diversity promotes competition for the best talents, effectively increasing a diverse customer base leading to an increased market share and freeing up creativity, innovation, and improved group problem solving (Jayne & Dipboye, 2004![]() ).

).

Issue 3: Changing leadership/adaptability.A good leader has an attitude that is prepared for change and has a sense of directiveness and assertiveness. That is, the leader should be able to model organizational values and a strong character at all times. The leader can anticipate and grasp new opportunities that are aligned with the strategic goals, as well as managing change by understanding its effects on organization and key strategies (Calarco & Gurvis, 2006![]() ).

).

4.4. Impact and Influence

Table 4 presents the issues raised by the focus group discussion in relation to impact and influence. Four issues were raised within this cluster.

Table 4. Issues regarding impact and influence.

| Cluster | Competency |

| Personal effectiveness | Impact and influence |

| Organizational and environmental awareness | |

| Networking/relationship building |

Issue 1: Impact and influence. AKEPT must assess the leader’s adaptive style – that is, their ability to adapt their personal leadership or approaches that can be used to influence others. The leader can make a case in terms of appeal to emotion and reason based on both data and concrete examples. The leader must also have the ability to stimulate his staff to take action and achieve goals even when a direct relationship does not exist (Yidong & Xinxin, 2013![]() ).

).

Issue 2: Organizational and environmental awareness. AKEPT must ensure that the leader can create an inclusive environment that respects the culture and community in their higher education institutions. The leader can adjust behavior based on cultural norms and cues, as well as appreciating the value of diversity in terms of creating and sustaining an environment where people from diverse backgrounds and perspectives can succeed (Zilahy & Huisingh, 2009![]() ).

).

Issue 3: Networking/relationship building. AKEPT should assess whether the leader has the ability to develop mutually beneficial relationships and partnerships based upon trust, respect and achievement of common goals. The leader also must be able to gain trust of the key stakeholders by listening and seeking to understand their views and needs (Ruben. & Gigliotti, 2019![]() ). The leader must be able to demonstrate respect and appreciation for others by showing empathy, valuing their time and contributions and responsive to their needs (Mohamed et al., 2020

). The leader must be able to demonstrate respect and appreciation for others by showing empathy, valuing their time and contributions and responsive to their needs (Mohamed et al., 2020![]() ).

).

4.5. Achievement and Action

Within this cluster, three issues have been identified to determine whether a leader in a higher education institution is competent. Table 5 presents the issues regarding achievement and action.

Table 5. Issues regarding achievement and action.

| Cluster | Competency |

| Leading | Achievement and orientation |

| Initiative and proactive behavior | |

| Information seeker |

Issue 1: Achievement orientation. AKEPT must assess whether the leader demonstrates high expectations by setting challenging goals for him- or herself, and also for others. The leader should take initiatives to go above and beyond typical expectations and make the sacrifices necessary to achieve exceptional results. The leader has flexibility in planning or when situations change unexpectedly, to ensure that they can effectively adjust those plans to achieve organizational outcomes (Xenikou & Simosi, 2006![]() ).

).

Issue 2: Initiatives and proactive behavior. AKEPT must assess whether the leader has the initiative ability to set both team and individual goals with employees that align with the vision and mission of the organization. In addition, the leader should be able to obtain resources, both monetary and non-monetary, to achieve team and individual goals. The leader should have the ability and initiative to set those goals for employees that align with the vision and mission of the organization (Albertyn & Frick, 2016![]() ).

).

Issue 3: Information seeker. A leader is an information seeker if he/she can gather information from multiple relevant sources and stakeholders in regard to problem solving. The leader can also deal with complex issues and identify useful relationships among complex data from unrelated areas (Gallup, 2018![]() ; Hobson et al., 2013

; Hobson et al., 2013![]() ). The leader has the characteristics of an individual who asks questions, looks for new ideas and is willing to research new ideas in order to become better informed (Chan & Misra, 1990

). The leader has the characteristics of an individual who asks questions, looks for new ideas and is willing to research new ideas in order to become better informed (Chan & Misra, 1990![]() ).

).

5. Conclusion

This study presents the development process of a leadership competency framework for higher education institutions in Malaysia, to address the issues in identifying competent leaders in those institutions. Using AKEPT as the setting and focus group discussion on competency committee members, this study demonstrates five clusters that must be included in the leadership competency framework: personal effectiveness, cognition, leading, impact and influence, and achievement and action. These clusters subsequently define the competency theme, consistent with previous studies. In each of the competency themes, several issues were highlighted which require the attention of AKEPT when assessing potential leaders. For example: under cluster 2 (cognition), one of the competency themes is relationships/networking. Under this theme, several issues were identified including conceptual thinking, analytical thinking, decision-making ability, and planning and organizing.

In sum, AKEPT provides a leadership competency framework for higher education institutions in determining a good leader. This framework comprises five clusters (see above) that require attention when assessing the abilities of a leader, and serves as an alternative to existing leadership competency frameworks in sustaining an organizational culture of excellence.

Citation| Ismie Roha Mohamed Jais; Nordin Yahaya; Erlane K Ghani (2020). Talent Management in Higher Education Institutions: Developing Leadership Competencies. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 8(1): 8-15. |

References

Albertyn, R., & Frick, L. (2016). A collaborative higher education initiative for leadership development: Lessons for knowledge sharing. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(5), 11-27.Available at: https://doi.org/10.20853/30-5-617.

Alias, R. A., & Abdul Rahman, A. (2003). Development of information systems service quality (Issq) model for institute of higher learning context. Paper presented at the Research Seminar RM7 & RM8, Aerospace, IT and Communication Focus Group, Johor Bahru.

Anderson, L. E. (2015). Relationship between leadership, organizational commitment, and intent to stay among junior executives. Walden Dissertation and Doctoral Studies, Walden University.

Axelrod, R. H. (2017). Leadership and self-confidence. In Leadership Today (pp. 297-313). Cham: Springer.

Bass, B. M. (1998). Transformational leadership: Industrial, military, and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Batliwala, S. (2010). Feminist leadership for social transformation: Clearing the conceptual cloud. New York: CREA.

Bechtel, B. C. (2010). An examination of the leadership competencies within a community college leadership development program. PhD Dissertation, University of Missouri.

Bensimon, E., Neumann, A., & Birnbaum, R. (1989). Making sense of administrative leadership: The ‘‘L’’ word in higher education. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1. Washington, DC: The George Washington University.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Rowe.

Calarco, A., & Gurvis, J. (2006). Adaptability: Responding effectively to change: Center for creative leadership. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Chan, K. K., & Misra, S. (1990). Characteristics of the opinion leader A new dimension. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 53-60.

Checkland, P. (1981). System thinking, systems practice. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Chouhan, V. S., & Srivastava, S. (2014). Understanding competencies and competency modeling―A literature survey. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(1), 14-22.Available at: https://doi.org/10.9790/487x-16111422.

Dirzyte, A., Patapas, A., Smalskys, V., & Udaviciute, V. (2013). Relationship between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and positive psychological capital in Lithuanian organizations. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(12), 115-122.

Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2007). Developing leadership capacity in college students: Findings from a national study. A Report from the Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Filan, G. L., & Seagren, A. T. (2003). Six critical issues for midlevel leadership in postsecondary settings. New Directions for Higher Education, 124(1), 21-31.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/he.127.

Filho, L. W., Eustachio, J. H. P. P., Caldana, A. C. F., Will, M., Salvia, A. L., Rampasso, I. S., . . . Kovaleva, M. (2020). Sustainability leadership in higher education institutions: An overview of challenges. Sustainability, 12(9), 1-21.

Gallup. (2018). Transform great potential into greater performance. Retrieved from: https://www.gallupstrengthscenter.com/.

Ghani, E. K., Muhammad, K., & Said, J. (2012). Development of integrated information management system service quality model in an accounting faculty. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7), 245-252.

Ghani., E. K., & Mohamed Jais, I. (2018). A gap analysis on leadership development course effectiveness in higher education in Malaysia, In N. P. Ololube (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of institutional leadership, policy and management. Port Harcourt: Pearl Publications.

Gigliotti, R. A., Ruben, B. D., & Goldthwaite, C. (2017). Leadership: Communication and social influence in personal and professional contexts. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Grol, R., & Wensing, M. (2013). Effective implementation of change in healthcare: A systematic approach, Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Health Care: Wiley & Sons.

Hobson, C., Strupeck, D., Griffin, A., Szostek, J., Selladurai, R., & Rominger, A. (2013). Field testing a behavioral teamwork assessment tool with US undergraduate business students. Business Education & Accreditation, 5(2), 17-27.

Jayne, M. E. A., & Dipboye, R. L. (2004). Leveraging diversity to improve business performance: Research findings and recommendations for organizations. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 409-424.

Katsinas, S. G., & Kempner, K. (2005). Strengthening the capacity to lead in the community college: The role of university-based leadership program. Lincoln, NE: National Council of Instructional Administrators.

Kirkpatick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? Academy of Management Perspectives, 5(2), 48-60.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). New York: Jossey-Bass.

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson's Research Reports, 6(1), 40-41.

Lucena, F. d. O., & Popadiuk, S. (2020). Tacit knowledge in unstructured decision process. RAUSP Management Journal, 55(1), 22-39.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/rausp-05-2018-0021.

Luthans, F. (2012). Psychological capital: Implications for HRD, retrospective analysis, and future directions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 23(1), 1-8.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21119.

McClelland, D. C. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for "intelligence. American Psychologist, 28(1), 1–14.

Mohamad, R. N. S., & Abdullah, C. Z. (2017). Leadership competencies and organizational performance: Review and proposed framework. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(8), 824-831.Available at: https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v7-i8/3297.

Mohamad, S. I. S., Muhammad, F., Hussin, M. Y. M., & Habidin, N. F. (2017). Future challenges for institutional leadership in a Malaysian education university. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(2), 778-784.

Mohamed, J., Yahaya, N., & Ghani, E. K. (2020). Development of a leadership competency framework for higher education institutions in Malaysia. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 14(1), 155-169.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 157-170.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0037-9.

Northouse, P. G. (2018). Leadership: Theory and practice (8th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peachey, J. W., Zhou, Y., Damon, Z. J., & Burton, L. J. (2015). Forty years of leadership research in sport management: A review, synthesis, and conceptual framework. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 570-587.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0126.

Radwan, O. A. A., Razak, A. Z. A., & Ghavifekr, S. (2020). Leadership competencies based on gender differences among academic leaders from the perspectives of faculty members: A scenario from Saudi higher education. International Online Journal of Educational Leadership, 4(1), 18-36.

Radwan., O., Ghavifekr, S., & Abdul Razak, A. Z. (2020). Can academic leadership competencies have effect on students’ cognitive, skill and affective learning outcomes. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, In press.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-05-2020-0144.

Rosen, A., & Callaly, T. (2005). Interdisciplinary teamwork and leadership: Issues for psychiatrists. Australasian Psychiatry, 13(3), 234-240.

Ruben, B. D., & Gigliotti, R. A. (2017). Are higher education institutions and their leadership needs unique? The vertical versus horizontal perspective. Higher Education Review, 49(3), 2752.

Ruben., B. D., & Gigliotti, R. A. (2019). Leadership, communication, and social influence: A theory of resonance, activation, and cultivation. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Smith, Z. A., & Wolverton, M. (2010). Higher education leadership competencies: Quantitatively refining a qualitative model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(1), 61-70.

Spencer, L., & Spencer, S. (1993). Competence at work: Model for superior performance. John Wiley & Sons: New York.

Taylor, K. L. (2005). Academic development as institutional leadership: An interplay of person, role, strategy, and institution. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(1), 31-46.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500099985.

Tellis, W. M. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3(2), 1-14.

Tichy, N. M. (1997). The leadership engine. New York: Harper Collins.

Wallin, D. (2009). Change agents: Fast-paced environment creates new leadership demands. Community College Journal, 22(1), 31-33.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89-126.

Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: Why it is so hard to teach? American Educator, 31(1), 8-19.

Xenikou, A., & Simosi, M. (2006). Organizational culture and transformational leadership as predictors of business unit performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(6), 566–579.

Yidong, T., & Xinxin, L. (2013). How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 441-455.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1455-7.

Yukl, G. (2002). Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Zilahy, G., & Huisingh, D. (2009). The roles of academia in regional sustainability initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(12), 1057-1066.

| Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |