Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Egypt: Challenges and Recommendations

Associate Professor, College of Education- Special Education Department, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, Saudi Arabia.

Abstract

The study aimed to examine challenges to the inclusion of Students with Disabilities (PWDs) in mainstream education in Egypt. A mixed method approach was used to collect data from various sources. First, statistical information was retrieved from the Ministry of Education (MoE). Secondly, Ministerial Decrees were examined. Thirdly, semi-structured interviews with specialists in the field of special education in Egypt (N=12) were conducted to explore the major issues that emerged from this study. Results revealed challenges facing the inclusion of PWDs in Egypt, such as a lack of in- & pre-service training of teachers, limitations of construction and preparation, lack of coordination among ministries, limited programs for students with certain disabilities, and lack of awareness in the community and the family. The study concluded that the successful inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools in Egypt requires, first, that universities consider inclusive education when training special education teachers; secondly, that professional development of teachers on inclusive education requirements is conducted, new policies are adopted, and school facilities are constructed with the needs of PWDs in mind; and thirdly, that the inclusion of PWDs not be limited to individuals with certain disabilities but must include students regardless of their type of disability.

Keywords:Inclusion, Students with disabilities, Egypt, Challenges, Training, Professional development.

Contribution of this paper to the literature: This study fills a gap in the literature concerning the state of special education services in Egypt and specifically the inclusion of PWDs in mainstream education.

1. Introduction

Egypt is the largest country in the Arab world by population, with 96 million inhabitants, most of whom live in the Nile Delta and Valley. However, although Egypt is the most populous Arab country, relatively little published research in the education literature has been conducted in Egypt, particularly in the field of special education. The last three decades have witnessed increasing attention to persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Egypt. This study will attempt to provide a description of the state of special education services in Egypt. In addition, the study will shed light on the most important challenges facing the process of inclusion and the development of these services, as well as some recommendations for improving the future of special education in Egypt.

2. Methods

A mixed method approach was used to collect data from various sources. First, statistical information was retrieved from the Ministry of Education (MoE) concerning Egypt's special education services. Secondly, a review was conducted of the various Ministerial Decrees regarding PWDs. Finally, semi-structured interviews with specialists in the field of special education in Egypt were also conducted to determine issues and recommendations on special education in Egypt.

2.1. Participants and Sampling Procedure

Twelve specialists in the field of special education in Egypt were interviewed – seven faculty members, and five teachers – to examine the major issues confronted by special education services in Egypt. Two stages of semi-structured interviews were conducted. In the first stage, the researcher began with the two general questions: What do you think of Egypt's special education services? What are the main issues or challenges facing special education in Egypt?

The interviews were conducted either face-to-face or via phone call, while the researcher took notes. Data from the initial interviews were collected, and themes were identified based on the responses. Based on the themes that emerged in the first stage, the main obstacles facing special education in Egypt were listed. Then, in the second stage, these themes were discussed with the focus group (10) individually in semi-structured interviews.

3. Data Analysis

The researcher used quantitative data and descriptive analyses (percentages and ratios) to obtain results. The data included numbers of special education programs, numbers of students with disabilities stratified according to disability, numbers of schools and classes, and numbers of teachers who teach these classes. Field visits and observations were conducted to obtain a deeper understanding. The researcher used data collected from observations during his visits and from interviews with selected special education professionals in Egypt.

In order to identify the challenges facing special education services in Egypt, the current reality of special education services must first be understood. Therefore, the next part of this study is divided into four sections. The first is a history of special education services in Egypt. The second is the current state of special education services. The third concerns the laws governing PWDs and their education, and the fourth describes the challenges facing special education services.

3.1. The History of Special Education in Egypt

Over the past few decades, many developments have taken place regarding special education in Egypt. The new legislation ensures the rights of PWDs, and the Egyptian government does its best to support all forms of care, including education, physical rehabilitation, and personal/social care (Ghobrial & Vance, 1988![]() ).

).

Egypt began to provide care for PWDs many years ago. In the Khedive Ismail era, beginning in approximately 1870, the government began to devote resources to teaching PWDs. From 1874 onwards, many schools were established for blind and deaf students. In 1900, a school for the blind was established in Alexandria to care for and teach PWDs. In 1927, the first Department of Education began to establish classes to teach blind students in governmental schools. In 1956, the Ministry focused on establishing the first institute for students with an intellectual disability. In 1957, the Ministry of Education focused on preparing teachers of PWDs by sending teachers to England for training. It was in 1950 that the Ministry of Education entrusted the supervision of schools for PWDs to the Department of Education (Ministry of Education, 2016![]() ).

).

The General Directorate for Special Education, within the Ministry of Education in Cairo, is responsible for the management, education, and supervision of PWDs. In 1964, it was transformed from a subsidiary to public administration management under the name of the "General Directorate of Special Education" (Laila, 1999![]() ).

).

3.2. Egypt and Care for PWDs

The government, as represented by the MoE in Cairo, is responsible for every aspect of the funding of special education schools. It is responsible for building schools, providing equipment, and providing the schools with teachers, administrators, guidance, counseling, monitoring, and evaluation processes (Mahna & Klilih, 1987![]() ). Other ministries also participate in the education process alongside the MoE, including the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Manpower (Fahmy, 2000

). Other ministries also participate in the education process alongside the MoE, including the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Manpower (Fahmy, 2000![]() ). Regarding financial and material support, many sources contribute to the funding of special education institutions, such as taxes, school fees, donations, local and international aid, and contributions from governments and charitable institutions and international agencies and organizations (Mahna & Klilih, 1987

). Regarding financial and material support, many sources contribute to the funding of special education institutions, such as taxes, school fees, donations, local and international aid, and contributions from governments and charitable institutions and international agencies and organizations (Mahna & Klilih, 1987![]() ). However, this funding is not specifically devoted to schools. Most of the ministries' contributions are financially weak, and the coordination and cooperation between the ministries are insufficient to provide adequate services to PWDs.

). However, this funding is not specifically devoted to schools. Most of the ministries' contributions are financially weak, and the coordination and cooperation between the ministries are insufficient to provide adequate services to PWDs.

3.3. Laws, Decrees, and Rights of PWDs

Few laws and ministerial decrees have been issued regarding the rights of PWDs and their inclusion in society. One example is Child Law No. 12 of 1996, which included a special chapter on the care and rehabilitation of children with disabilities. Also, Ministerial Decree (2008![]() ) No. 42 ensured the formation of a committee to promote the inclusion of PWDs in public education by identifying and developing the necessary operational framework. Ministerial Decree (2009

) No. 42 ensured the formation of a committee to promote the inclusion of PWDs in public education by identifying and developing the necessary operational framework. Ministerial Decree (2009![]() ) No. 94, dated 04/28/2009, has ensured the inclusion of children with mild disabilities in all stages of public school. The same decree stressed the need to provide enrichment activities and other resources within the school to meet the needs of all children of different abilities.

) No. 94, dated 04/28/2009, has ensured the inclusion of children with mild disabilities in all stages of public school. The same decree stressed the need to provide enrichment activities and other resources within the school to meet the needs of all children of different abilities.

3.4. Non-Educational Efforts

Another effort to facilitate the demands of life for PWDs is to facilitate transportation services at affordable prices for PWDs as part of the responsibility to all segments of society. For instance, in 2006, the Ministry of Transport reduced ticket prices for PWDs by 92% and adjusted the rates for the Metro similarly.

3.5. Current Special Education Services

The teaching of PWDs in Egypt has, until recently, been based on a system in which independent special education schools are the prevailing model to provide education to PWDs. The national strategic plan for the reformation of pre-university education in Egypt NSP (2008![]() ) ensured that these students would be supported by special education services through specialized schools and sometimes through independent special classes within public schools. Egypt has recently started to move toward the inclusion of PWDs in public education. The MoE has adopted a number of protocols such as the full inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools, as an experimental venture, or their partial inclusion in mainstream schools. NSP (2008

) ensured that these students would be supported by special education services through specialized schools and sometimes through independent special classes within public schools. Egypt has recently started to move toward the inclusion of PWDs in public education. The MoE has adopted a number of protocols such as the full inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools, as an experimental venture, or their partial inclusion in mainstream schools. NSP (2008![]() ) and NSP (2012

) and NSP (2012![]() ) of the MoE announced a revised version of the NSP that ensured the right of PWDs to be included with their peers. The revised NSP also emphasized the training of teachers in order to fulfil the requirements of the philosophy of inclusion. However, many obstacles exist regarding implementing these strategic plans, such as a large number of laws and bureaucracy, a dependency on central decision-making, and the apparent slow implementation of the services.

) of the MoE announced a revised version of the NSP that ensured the right of PWDs to be included with their peers. The revised NSP also emphasized the training of teachers in order to fulfil the requirements of the philosophy of inclusion. However, many obstacles exist regarding implementing these strategic plans, such as a large number of laws and bureaucracy, a dependency on central decision-making, and the apparent slow implementation of the services.

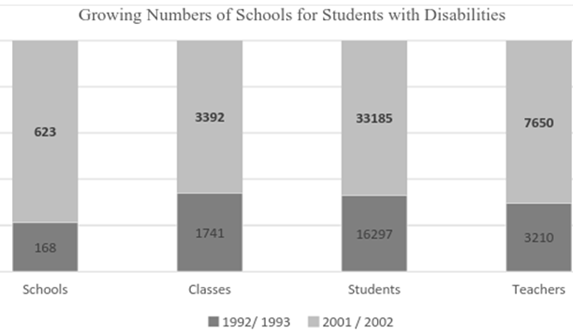

Statistics from the MoE in Egypt (2001-2002) indicate an increase in the number of teachers, schools, classrooms, and students between 1992 and 2001. Table 1 and Figure 1 show the numbers and increases.

Table-1. The number of teachers, schools, classrooms, and students between (1992 – 2001).

School year |

Schools |

Classes |

Students |

Teachers |

1992/1993 |

168 |

1741 |

16297 |

3210 |

2001/2002 |

623 |

3392 |

33185 |

7650 |

Percent increase |

370.8% |

194.8% |

203.6% |

238.3% |

Figure-1. Increases in the numbers of schools, classes, and teachers serving students with disabilities between (1992-2001).

Table 1 shows significant increases in the numbers of schools, classes, and teachers serving students with disabilities between 1992 and 2001. This change is perceived as a good indicator of the development of services for PWDs in Egypt. However, these numbers also show that only a fraction of PWDs are receiving special education services.

The total number of students with a disability at each education stage in Egypt, according to the MoE data (2001-2002), including students who are blind, deaf, and hard of hearing and those with intellectual disabilities, is provided in Table 2.

Table-2. According to the MoE data, the number of students with disabilities at various stages of education in Egypt (2001-2002).

| Stages | Number of schools |

Number of classes |

Number of students |

Number of teachers |

| Elementary School | 391 |

2563 |

23540 |

5291 |

| Middle School | 78 |

852 |

7165 |

324 |

| Vocational Middle School | 139 |

520 |

6315 |

677 |

| Secondary School | 59 |

210 |

2519 |

248 |

| Total | 667 |

4145 |

39539 |

6540 |

Note: The significant increase in the number of PWDs is apparent, particularly in elementary schools.

3.6. Teachers of PWDs

According to a statement from the Director of the MoE in January 2002, approximately 1774 specialist teachers (graduates from special education departments of colleges) and non-specialist teachers worked in special education schools and programs (Director of MoE, 2002![]() ).

).

At the first Arab National Conference for Special Education (1995, 75), the MoE indicated that many graduates have a desire to work in the field of special education. In particular, non-educators who receive a General Diploma in Education from colleges of education are keen to work as teachers in special education schools to obtain a financial incentive (80% of the basic salary) or for an opportunity to work in Arab countries.

3.7. Steps and Decrees on the Inclusion of PWDs

Like other Arab countries, Egypt still lacks requirements for the inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream schools, although steps have been taken in this direction. In the first conference concerning the inclusion of PWDs in public education held in 2002 in Cairo, the Egyptian Minister of Education said that, with the World Bank and UNESCO's support, inclusion had been achieved in 270 schools in Egypt. Many ministerial decisions have been issued in favor of the inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools.

One of the most promising movements in Egypt concerning the inclusion of PWDs was the National Strategic Plan for Education Reform that was developed (2007-2008/2011-2012) to enhance the inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools. The program is based on the following methodology: prepare for the inclusion of PWDs in mainstream schools, provide sustainable developmental services (for teachers and specialists), align the curriculum with the needs of children who are in general education classes, modify school buildings to suit the physical condition of PWDs, improve the quality of education in all special education schools, develop national legislation and policies to provide a supportive environment, and finally, raise awareness and form positive relationships between the civil and educational communities (NSP., 2008![]() ).

).

These steps were devised to achieve three main objectives for the inclusion of PWDs: the inclusion of 10% of children with mild disabilities in primary schools by 2012 and improvements in the quality of education provided to them, improvements in the quality of education at schools for PWDs, and the provision of a supportive environment for inclusion processes in primary schools. However, these goals have not yet been achieved due to the increasing number of available schools for PWDs and the lack of an appropriate infrastructure for the inclusion process, particularly in primary schools.

3.8. Challenges to Inclusion

Special education services are still in the early stages in Egypt. However, even though the services are limited, there are many challenges in the delivery of these services. Soliman (2009![]() ) studied the problems that hinder the inclusion of PWDs in primary schools in Egypt. The study relied on the Delphi method and included 80 teachers and managers of primary schools. The author identified several problems, including a lack of safety in school buildings, a high student to teacher ratio in mainstream classes, and poor knowledge of the characteristics of PWDs on the part of teachers and managers. Thus, all schools that include special education programs should be built to include modern equipment and support services. Many schools include students with different disabilities, and each disability has different requirements for the inclusion process.

) studied the problems that hinder the inclusion of PWDs in primary schools in Egypt. The study relied on the Delphi method and included 80 teachers and managers of primary schools. The author identified several problems, including a lack of safety in school buildings, a high student to teacher ratio in mainstream classes, and poor knowledge of the characteristics of PWDs on the part of teachers and managers. Thus, all schools that include special education programs should be built to include modern equipment and support services. Many schools include students with different disabilities, and each disability has different requirements for the inclusion process.

3.9. Challenges and Future Attitudes

Although Egypt is considered a leader of the Arab world in many educational fields, special education remains in its early stages. Based on the interviewees’ responses, a number of issues must be considered before substantial changes can be made regarding the quality and quantity of special education services for students with disabilities.

3.9.1. Lack of in- & Pre-service Training

The training of special education teachers in Egypt is a topic that needs more attention. Although there is a long history – the training of teachers of PWDs began in 1926, when the Ministry of Education began to prepare teachers to work with blind students – it has faced many obstacles.

The absence of special education departments, and other programs to prepare teachers, leads to teachers who are insufficiently qualified to work with PWDs because they have studied only general concepts, knowledge, and information. Special education teachers require more training to cope with modern developments and trends that currently cannot be offered to students due to a lack of trained staff. A moderate proportion of teachers with higher education degrees have graduated from special education departments of colleges of education, but this number needs to increase. One participant noted,

"The amount of in-service training for teachers who work with PWDs for modern and advanced care of PWDs that includes modern educational theories and methods of teaching is not sufficient. Most of the teachers are not educationally well-qualified".

As a result, the Egyptian MoE initiated an expansion of the special education departments at Egyptian universities. The first Department of Special Education was established at Ain Shams University. Furthermore, a Faculty of Science for Special Needs exists at Beni Suef University, and a College of Disability and Rehabilitation has been established at Zagazig University.

Although these efforts were needed, a careful reconsideration of special education teachers' training is still necessary. Both pre-service and in-service teachers should take part in continuous training in all new programs and techniques.

Inclusion requires well-prepared teachers who are capable of working with PWDs. Some teachers are educationally qualified, but others must be retrained to work with PWDs to further the inclusion process. Currently, there are an insufficient number of special education teachers available in inclusive schools.

On the other hand, the increase in the number of PWDs in Egypt between 1996 (2,060,536) and 2016 (2,899,180) has hampered the process of inclusion of PWDs with their peers without disabilities because mainstream schools are unable to accommodate this large number of students with different disabilities.

As a result, more relevant special education teacher training colleges must be established and the existing ones expanded, along with an increase in the number of paths to include most disability categories. This strategy would facilitate the inclusion of PWDs with their peers because sufficient teachers will then have the skills to work with PWDs.

One participant said,

"A database should be created containing all matters relating to PWDs, which should be available for teachers of PWDs, and 'distance education' should be used as a method to prepare special education teachers. In addition, special education teachers' training needs should be identified through questionnaires and surveys, and the use of workshops, training days and group seminars must be expanded."

3.9.2. Limitations of Construction and Preparation

A large gap exists between the number of PWDs and the schools and classes available to them. The increasing number of PWDs has not been matched by an appropriate increase in the numbers of schools, classrooms, and teachers. According to statistics from the MoE, in 1992 there were 168 schools, 1,741 classes, 16,297 students, and 3,210 teachers. In contrast, in 2002, 623 schools, 3,392 classes, 33,185 students, and 7,650 teachers were identified, reflecting an increase of approximately 238.3%.

One of the participants noted that "Few schools have special education programs, and they lack the necessary equipment for the education of PWDs, such as resource rooms and libraries."

Schools that provide facilities for PWDs are generally only those in the big cities. Another participant stated that "Most schools that are acceptably equipped are concentrated in cities and large-sized educational administrations."

3.9.3. Lack of Coordination

Many ministries are responsible for PWDs in Egypt, including the MoE, the Ministry of Social Affairs (which provides rehabilitation services to PWDs), the Ministry of Health (which provides healthcare), and the Ministry of Manpower (which provides jobs for PWDs) (Ghobrial & Vance, 1988![]() ). However, the lack of coordination between these ministries leads to a loss of time, effort, and money. One participant noted,

). However, the lack of coordination between these ministries leads to a loss of time, effort, and money. One participant noted,

"We need a mechanism of coordination between charities and institutions responsible for the care of PWDs as well as between the official government ministries that offer different services."

One of the respondents believed that

"The responsibility for PWDs belongs to the Ministry of Education, but no coordination exists between the MoE and other ministries, such as the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Manpower, and the Ministry of Social Affairs."

Another participant stated,

"Although many ministries, civil associations, and organizations provide services for PWDs, the introduction of different services is not coordinated, which leads to the duplication of many services."

Another participant commented,

"Most of the services offered by the ministries are concentrated in major cities, such as Cairo and Alexandria; on the other hand, few services are available in small towns, villages and remote areas."

The distribution of services for PWDs should be based on criteria such as geography and easy access to these services by beneficiaries.

3.9.4. Limited Programs for Students with Certain Disabilities

Special education programs are currently limited to specific categories, such as intellectual disability, hearing impairment, visual impairment, and autism. Few programs are available for students with other disabilities.

One participant in the study sample said,

"Special education in Egypt has deficiencies in the provision of services for students with different disabilities, such as those with learning disabilities, physical disabilities and speech disorders."

Another participant stated,

"Few programs provide rehabilitation and transitional services for PWDs, such as the inclusion of PWDs in the educational environment or society."

The MoE should therefore focus on providing other special education classes and establishing programs for these students, particularly for the increasing number of individuals with learning disabilities and behavioral disorders.

A major obstacle to implementing the inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream schools is that most schools have children with a range of disabilities but do not have teachers who have specialized in these paths. To overcome this problem, special education paths should be expanded to include all disabilities.

3.9.5. Lack of Awareness in the Community and the Family

A lack of coverage of PWDs in the media, particularly the television media, has been noted. Only a few television programs of a short duration focus on PWDs. One of the study participants said,

"A timetable or schedule for PWD programs is not available. Random programs are limited to people with certain disabilities, such as deafness, autism and intellectual disability, neglecting other disabilities".

Another participant said,

"The awareness and care programs for PWDs are few in number, compared to the large number of PWDs in Egypt. Besides, the number of primary prevention programs should be increased to prevent disability. And other programs, such as early intervention, should be increased to guide the families of the disabled persons".

In short, programs that serve PWDs must be expanded and be advertised via various media outlets. Interpreters must be provided for deaf people using sign language. And there is a need for parents and all interested people to participate in the implementation of policies and legislation that serve PWDs, and to activate civil associations and charities. Additionally, the private sector should be encouraged to invest in special education programs and services. Finally, cooperation is necessary between families of PWDs, schools, and administrations to develop and participate in programs for early intervention and individual plans.

4. Conclusions

In many educational fields, Egypt is considered a leader in the Arab world, but special education in the country remains in the early stages. The education of students with disabilities has not received the appropriate level of attention to increase the quality and quantity of services. The successful inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream schools in Egypt requires certain steps to be taken. First, universities should have inclusive education in mind when training special education teachers as well as teachers of other disciplines. Teachers should be ready to work in environments with students of varying abilities, but this requires them to be properly trained. Secondly, the further professional development of teachers on the requirements of inclusive education is needed. New policies must be adopted, and school facilities should be constructed with the needs of PWDs in mind. Thirdly, the inclusion of PWDs should not be limited to individuals with certain disabilities, such as intellectual disabilities or blindness, but must include most people regardless of their type of disability.

Citation| Ayman Elhadi (2021). Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Egypt: Challenges and Recommendations. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 8(2): 173-178. |

References

Director of MoE. (2002). Interview with the Director of the ministry of education. Riyadh: Ministry of Education.

Fahmy, M. (2000). The reality of the care of the disabled in the Arab world (pp. 158-159). Alexandria: The Modern University Office.

Ghobrial, T., & Vance, R. (1988). Special education in Egypt: An overview. Washington DC: Education Resources Information Center, Institute of Education Sciences.

Laila, J. (1999). The reality of persons with disabilities in Egypt (pp. 117-122). Cairo: The National Center for Social and Criminological Research.

Mahna, G., & Klilih, H. (1987). Special education for the disabled. Mansoura The Modern Scientific Library.

Ministerial Decree. (2008). Ministerial Decree No. 42 The formation of a committee to integrate PWDs at public schools. Cairo: Ministry of Education.

Ministerial Decree. (2009). Ministerial Decree No.94 on the admission of students with mild disabilities in schools that are configured and prepared to receive those students. Cairo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2016). History of special education in Egypt. Cairo: Ministry of Education.

NSP. (2012). National strategic plan for pre-University education reform in Egypt (2007-2008 / 2011-2012). Cairo: Ministry of Education.

NSP. (2008). The public education sector, the Central Department for Basic Education, the General Directorate for Special Education (pp. 35). Cairo: Technical Guidance and Administrative Instructions for Schools and Special Education Classes.

Soliman, H. (2009). The roles and the basic problems of the Department of Education in Egypt in achieving the inclusion of people with disabilities "prospective study". The Egyptian Association for Comparative Education and Educational Administration, 25(1), 1-25.

| Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |