Teachers' Perceptions of the Role of Universities in Mentoring Programs for Inclusive Elementary Schools: A Case Study in Indonesia

1,2Department of Elementary School Teacher Education, Universitas Djuanda, Indonesia.

3 Department of Elementary School Teacher Education, Universitas PGRI Adibuana Surabaya, Indonesia.

Abstract

The key problem with implementing inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools in Indonesia is that the role of all stakeholders in creating mentoring programs must be continuous and sustainable. The purpose of this study is to explore the opinions of general teachers (GTs) regarding the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews with 32 GTs in inclusive elementary schools. Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis of qualitative data. The results show two main themes, namely university involvement, and inclusive education resource centers. The roles of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools are the development of effective instruction systems and the provision of human resources who are competent at implementing inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools. This research is expected to be the basis for policymakers, especially in universities, to design appropriate and relevant mentoring programs for the problems faced by inclusive elementary schools.

Keywords:Mentoring program, Elementary school, Inclusive education, Indonesia.

Contribution of this paper to the literature: This study contributes to existing literature by exploring the opinions of general teachers (GTs) regarding the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools.

1. Introduction

The Indonesian government is in the process of implementing inclusive education in Indonesia to provide education for all citizens, including special needs students (SNSs). To succeed in implementing inclusiveness, it is not only the government's obligation but also that of all stakeholders, including universities, that have significant resources for developing inclusive practices (Wells, 2019![]() ). As an expert authority in developing and producing student teachers who can teach in inclusive schools, the university is expected to play a more active role. One of these active roles can be implemented in inclusive elementary schools, which currently still require special attention due to the increasing number of SNSs at the elementary school level in Indonesia.

). As an expert authority in developing and producing student teachers who can teach in inclusive schools, the university is expected to play a more active role. One of these active roles can be implemented in inclusive elementary schools, which currently still require special attention due to the increasing number of SNSs at the elementary school level in Indonesia.

The higher the number of SNSs at elementary schools in Indonesia, the more inclusive elementary schools must be available to provide equitable services in education (Haryono, Syaifudin, & Widiastuti, 2015![]() ). However, the growing number of inclusive elementary schools is also increasingly visible. Problems faced by inclusive elementary schools include:

). However, the growing number of inclusive elementary schools is also increasingly visible. Problems faced by inclusive elementary schools include:

Many schools have not received continuous assistance from the government in implementing inclusive education practices (Engelbrecht, Nel, Smit, & Van Deventer, 2016![]() ).

).

- A lack of training to improve inclusive teacher competence.

- Schools not yet collaborating with other parties (universities, NGOs, psychologists) in supporting the implementation of inclusive education, resulting in schools feeling as if they bear all the inclusive education obligations.

- A gap between the theory and practice obtained by student teachers at universities when they have to teach in inclusive elementary schools.

- Schools do not yet have adequate facilities or infrastructure to accommodate the needs of all students (Zelina, 2020

).

).

There has not, to date, been a special unit that can assist teachers in solving problems in inclusive classrooms such as those related to the curriculum or student behavior and assessment.

Problems and obstacles in the implementation of inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools must be met with solutions to achieve the goals of inclusive education in Indonesia. For this reason, the role of universities as problem-solvers for challenges that occur in inclusive elementary schools is significant. Universities have the authority as sources of research. They can oversee research results in the form of recommendations and academic policies that can have long-term impacts on improving the implementation of inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools (Domović, Vidović, & Bouillet, 2017![]() ; Maddamsetti, 2018; Saniya, Widodo, Suyatno, & Santosa, 2020

; Maddamsetti, 2018; Saniya, Widodo, Suyatno, & Santosa, 2020![]() ) . Universities must create productive collaboration between universities and inclusive elementary schools as reciprocal relationships to produce inclusive student teachers with quality competencies (Ellis, Alonzo, & Nguyen, 2020

) . Universities must create productive collaboration between universities and inclusive elementary schools as reciprocal relationships to produce inclusive student teachers with quality competencies (Ellis, Alonzo, & Nguyen, 2020![]() ; Kinsella, 2020

; Kinsella, 2020![]() ). Student teachers who graduated as elementary school teachers at university must implement the theory they learned during their lectures when they go on to teach in inclusive elementary schools. The problems faced by inclusive elementary schools, including general teachers (GTs), can be appropriately improved. The reciprocal relationship between universities and inclusive elementary schools is expected to have a long-term positive impact (Zagona, Kurth, & MacFarland, 2017a

). Student teachers who graduated as elementary school teachers at university must implement the theory they learned during their lectures when they go on to teach in inclusive elementary schools. The problems faced by inclusive elementary schools, including general teachers (GTs), can be appropriately improved. The reciprocal relationship between universities and inclusive elementary schools is expected to have a long-term positive impact (Zagona, Kurth, & MacFarland, 2017a![]() ) in enhancing the inclusive education system in Indonesia.

) in enhancing the inclusive education system in Indonesia.

Universities must realize the role of their institutions in assisting the implementation of inclusive education through real solutions such as continuous mentoring programs to impact inclusive elementary schools positively (Betlem, Clary, & Jones, 2019![]() ; Rahill, Norman, & Tomaschek, 2017

; Rahill, Norman, & Tomaschek, 2017![]() ). The process of solving problems for inclusive elementary schools with a mentoring program can be a mutually beneficial collaboration for both parties. Meanwhile, the problems faced by inclusive elementary schools can be partly resolved by universities developing lecture materials so that student teachers have relevant competencies (Frazier, 2018

). The process of solving problems for inclusive elementary schools with a mentoring program can be a mutually beneficial collaboration for both parties. Meanwhile, the problems faced by inclusive elementary schools can be partly resolved by universities developing lecture materials so that student teachers have relevant competencies (Frazier, 2018![]() ). Student teachers who plan to teach in inclusive elementary schools in the future are expected to reduce the gap between the theory and the practical implementation of inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools.

). Student teachers who plan to teach in inclusive elementary schools in the future are expected to reduce the gap between the theory and the practical implementation of inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools.

The purpose of this study is to explore the opinions of GTs on the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools.

2. Method

The purpose of the study is to explore the perceptions of GTs regarding the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools. The researcher used case study research by conducting in-depth interviews with GTs of inclusive elementary schools who teach in inclusive classrooms. A qualitative design was used to explore GTs' opinions regarding the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools. The university used in the research is a higher education institution that organizes a faculty of education with an elementary school teacher education department that produces graduates or teacher students who will teach in inclusive elementary schools in the future. In this way, GTs provide their opinions regarding the role of universities in inclusive elementary school mentoring programs. The opinions of these GTs are significant as input for universities so that the inclusive elementary school mentoring program evolves to be on target and relevant to the implementation of inclusive education in elementary schools.

3. Participants

The participants in this study were 32 inclusive elementary school general teachers (GTs) from schools designated as model inclusive elementary schools and general elementary schools that accept SNSs. The GTs come from 32 inclusive elementary schools from five regions in Indonesia and have experience teaching inclusive classes. Each participant was selected using recommendations from the principal in each region. Selected participants were contacted using telephone and WhatsApp to set interview times. Interviews were conducted both online and offline. Online interviews used the Zoom application, while researchers met face-to-face with respondents for the offline work. A total of 32 participants were selected, consisting of 29 female and three male teachers with the qualifications and criteria of having taught for at least one year in inclusive classrooms with various characteristics of SNSs. Their profiles are shown in Table 1.

Table-1. Profile of the respondents.

Frequency |

% |

|

Gender |

||

Female |

29 |

90.6 |

Male |

3 |

9.4 |

Working years as a teacher |

||

1-5 years |

13 |

40.7 |

6-10 years |

9 |

28.1 |

11-15 years |

5 |

15.6 |

16-20 years |

5 |

15.6 |

21 years |

||

Level of education |

||

Bachelor's |

27 |

84.4 |

Masters |

0 |

0 |

Others |

5 |

15.6 |

4. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected using in-depth interviews. In addition to the three main researchers who conducted interviews, two field assistants with experience in collecting interview data were also involved. Interviews were conducted between March and April 2021 with a duration of 1 to 1.5 hours. The interviews used an interview guide that two inclusive education experts had previously validated. The interview technique was semi-structured and explored GTs' experiences and opinions on the problems they have faced in inclusive classrooms. In addition, GTs were asked for advice on mentoring programs that universities must pursue for inclusive elementary schools to help inclusive elementary schools resolve problems. Background information such as teacher demographics (i.e., gender, number of years of teaching, education level) was also collected.

5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify, evaluate and produce the theme expressed by participants (Galloway & Jenkins, 2009![]() ). The interviews conducted were transcribed verbatim, sorted, and categorized according to emerging themes around the role of mentoring programs that universities must carry out for inclusive elementary schools. To make coding and categorizing easier, the researchers used the NVivo 12 program. First, interview data were entered into nodes and codes to be grouped into data with relevant codes. Thematic maps showed concepts according to various levels, and potential interactions between concepts were then developed. Second, the research team members discussed all the emergent codes and categorizations, which included simplifying the code by integrating several similarities. The next step produced the main themes addressed in the next stage of this research.

). The interviews conducted were transcribed verbatim, sorted, and categorized according to emerging themes around the role of mentoring programs that universities must carry out for inclusive elementary schools. To make coding and categorizing easier, the researchers used the NVivo 12 program. First, interview data were entered into nodes and codes to be grouped into data with relevant codes. Thematic maps showed concepts according to various levels, and potential interactions between concepts were then developed. Second, the research team members discussed all the emergent codes and categorizations, which included simplifying the code by integrating several similarities. The next step produced the main themes addressed in the next stage of this research.

During the research process, credibility and dependability were well-considered, starting with the data collection instrument used based on a literature review relevant to the research topic. The interview guide was designed using expert opinions, namely two inclusive education experts. After data was collected, member checking (Lincoln & Guba, 1985![]() ) was used to check credibility, where the participants (32 GTs) were asked to clarify that the outcome accurately reflected their contribution to the data that had been collected and analyzed. Triangulation of the three main researchers and two additional researchers at all stages of the study was carried out to maintain data dependability (Patton, 2014

) was used to check credibility, where the participants (32 GTs) were asked to clarify that the outcome accurately reflected their contribution to the data that had been collected and analyzed. Triangulation of the three main researchers and two additional researchers at all stages of the study was carried out to maintain data dependability (Patton, 2014![]() ). Researcher triangulation helps researchers overcome bias by facilitating cross-checking of the integrity of the participants' responses (Anney, 2014

). Researcher triangulation helps researchers overcome bias by facilitating cross-checking of the integrity of the participants' responses (Anney, 2014![]() ). The involvement of all researchers with the same problem will bring different points of view into the investigation so that the integrity of the findings in the study receives good support.

). The involvement of all researchers with the same problem will bring different points of view into the investigation so that the integrity of the findings in the study receives good support.

6. Findings

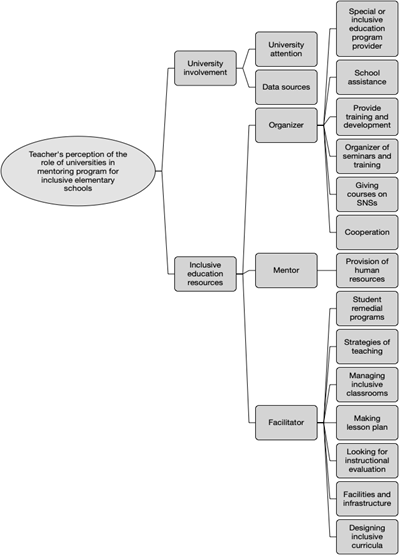

The research findings show that GTs' perception of the role of universities in inclusive elementary school mentoring programs follows two main themes, namely university involvement, and inclusive education resource centers. See Figure 1.

6.1. University Involvement

Concerning university involvement, sub-themes about data sources and university attention were generated. GTs perceive the university as a data source for researchers to conduct various studies, the results of which are expected to be implemented in inclusive elementary schools. In addition, universities are a source of information on research results, especially on inclusive education. If there are problems related to inclusive education, GTs can ask the university for solutions. This opinion is as perceived by two of the GTs thus:

"Universities are the source of research data, so I hope that if I face a problem in my class, I can rely on research results from the university" (GT 4).

"I hope the research results produced by the university can be implemented in inclusive schools so that it can help solve the problems that I have faced so far" (GT 10).

Figure-1. Data analysis (with Nvivo 12).

GTs perceive that the role of universities in mentoring programs is expected to provide further support, especially in solving inclusive education problems. So far, many inclusive schools, especially in remote rural areas, have received little attention from universities. As a result, GTs and inclusive elementary schools, when facing problems in inclusive classrooms, do not know who to go to for solutions to their problems. Various challenges occur in inclusive classrooms, such as issues with understanding the characteristics of SNSs. Many GTs do not understand or identify SNSs, because GTs' backgrounds are not from special education study programs or inclusive education.

For this reason, GTs hope that the role of universities will be focused on essential points in handling inclusive classrooms. The attention that GTs expect includes continuous assistance that can provide an in-depth understanding so that it can solve the problems faced so far. This opinion is as explained by a GT thus:

"I hope universities can give attention such as continuous assistance to inclusive schools, so that when we face problems the university can help" (GT 20).

University involvement is a key role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools, and they are expected to make a significant contribution (Howell et al., 2021![]() ). As a result, the problems faced by inclusive schools can be adequately resolved.

). As a result, the problems faced by inclusive schools can be adequately resolved.

6.2. Inclusive Education Resource Center

The findings on an inclusive education resource center resulted in three sub-themes, namely facilitator, mentor, and organizer. The role of a university as a facilitator is expected to involve facilitating all-inclusive activities or practices between activities that have been going well with the problems often faced by GTs in inclusive classrooms (Mahajan & Suresh, 2017![]() ; Williams et al., 2001

; Williams et al., 2001![]() ). Universities can facilitate essential aspects in helping GTs and inclusive elementary schools both in academic and non-academic aspects. Several academic and non-academic aspects that are expected to be facilitated by the university as expected by GTs include making lesson plans, managing inclusive classrooms, looking for instructional evaluation models in inclusive classrooms, designing inclusive curricula, implementing student remedial programs, supporting facilities and infrastructure, and creating teaching strategies.

). Universities can facilitate essential aspects in helping GTs and inclusive elementary schools both in academic and non-academic aspects. Several academic and non-academic aspects that are expected to be facilitated by the university as expected by GTs include making lesson plans, managing inclusive classrooms, looking for instructional evaluation models in inclusive classrooms, designing inclusive curricula, implementing student remedial programs, supporting facilities and infrastructure, and creating teaching strategies.

Both aspects -academic and academic- are expected to provide long-term solutions for GTs. For example, as facilitators, universities are expected to assist GTs and inclusive elementary schools in designing a curriculum that is appropriate to the characteristics of the schools and their students. It is also important that universities can facilitate the latest instructional strategies for GTs to practice in inclusive classrooms, such as teaching methods, so they can achieve instruction objectives according to all student needs. GTs are facilitated for instructional methods and instructional media that all students can access through the latest research results by the university. Below, GTs explain this opinion:

"Our school has not been able to design a curriculum, or determine which curriculum is most suitable for good use. We hope the university can help us overcome this" (GT 15).

"I hope the university can facilitate us with methods, media, and the latest teaching methods in inclusive classrooms so that learning can be carried out smoothly and we can achieve instructional objectives" (GT 30).

Apart from being a facilitator, the university also acts as a mentor for inclusive elementary schools. As a mentor, the university is a source or center for inclusive education experts. In particular, universities can provide human resources to support and assist in providing resources in inclusive elementary schools (Winslade, 2016![]() ). However, a common human resources problem in inclusive elementary schools is the unavailability of special assistant teachers (SATs) to accompany and assist GTs in dealing with SNSs. Therefore, universities are expected to organize more study programs related to the provision of SATs so that graduates can assist SNSs in inclusive classrooms. This opinion can be explained by one of the GT's opinions:

). However, a common human resources problem in inclusive elementary schools is the unavailability of special assistant teachers (SATs) to accompany and assist GTs in dealing with SNSs. Therefore, universities are expected to organize more study programs related to the provision of SATs so that graduates can assist SNSs in inclusive classrooms. This opinion can be explained by one of the GT's opinions:

"Universities should organize a lot of programs for assistant teachers in inclusive classrooms" (GT 1).

Apart from providing trained SATs, universities are a source of experts and professionals in inclusive education. The university is expected to involve these experts in solving and providing solutions to the problems faced by GTs. GTs hope that professional experts can provide assistance or provide professional assistance according to the needs of inclusive schools. For example, professionals can help improve GT competence after their teacher training qualifications are obtained. This opinion is explained by one of the GTs below:

"Professionals at universities are expected to help us improve our competence so that we have more skills" (GT 6).

Universities are also expected to organize inclusive elementary school mentoring programs. As organizers, universities can plan and implement several programs or activities to support inclusive education in inclusive schools (Sharma, Armstrong, Merumeru, Simi, & Yared, 2019![]() ). Several programs include creating collaborations between inclusive elementary schools or parties related to inclusive education, providing courses or short courses on inclusive education in study programs, providing training, development, or seminars to GTs on inclusive education, and mentoring inclusive elementary schools in continuous ongoing programs.

). Several programs include creating collaborations between inclusive elementary schools or parties related to inclusive education, providing courses or short courses on inclusive education in study programs, providing training, development, or seminars to GTs on inclusive education, and mentoring inclusive elementary schools in continuous ongoing programs.

Universities have the authority and abilities to organize continuous mentoring programs so that inclusive schools can benefit from long-term impacts (Bailey, 2013![]() ; Burstein, Sears, Wilcoxen, Cabello, & Spagna, 2004

; Burstein, Sears, Wilcoxen, Cabello, & Spagna, 2004![]() ). Several programs, such as organizing seminars or training courses that are carried out continuously, provide opportunities for GTs to develop themselves optimally. In training, universities can also assist GTs in understanding SNSs better. Some opinions from GTs can be seen below:

). Several programs, such as organizing seminars or training courses that are carried out continuously, provide opportunities for GTs to develop themselves optimally. In training, universities can also assist GTs in understanding SNSs better. Some opinions from GTs can be seen below:

"I hope that with seminars or intense training, I can develop myself to be better" (GT 10). "In training, I hope that the university can provide courses on understanding students with special needs because this is very important" (GT 11).

GTs perceptions of the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools are based on the active participation of universities to realize more effective long-term programs. The role of universities in inclusive elementary schools is a reciprocal relationship that will positively impact both in the future.

7. Discussion

The practice of inclusive education in Indonesia requires positive cooperation between all relevant stakeholders. For this reason, the obligation to succeed in inclusive education is not only the responsibility of the government but also the duty of universities. However, the role of universities in Indonesia in implementing inclusive education has, in the past, been limited to the provision of special education study programs, including the implementation of inclusive education courses in elementary school teacher education programs. When inclusive teachers graduate from university, they are required to solve problems in increasingly varied inclusive classrooms. For this reason, one form of university participation in the successful implementation of inclusive education in the future is to conduct a mentoring program for inclusive elementary schools.

The role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools is one way to help solve problems faced by inclusive elementary school teachers, especially GTs (Hoppey & McLeskey, 2013![]() ; Zagona, Kurth, & MacFarland, 2017b

; Zagona, Kurth, & MacFarland, 2017b![]() ). The role of universities is expected to have a positive impact on the implementation of inclusive education. University involvement in mentoring programs for inclusive schools can make use of the university's capacity as a research center and research data source (Causton-Theoharis, Theoharis, Bull, Cosier, & Dempf-Aldrich, 2011

). The role of universities is expected to have a positive impact on the implementation of inclusive education. University involvement in mentoring programs for inclusive schools can make use of the university's capacity as a research center and research data source (Causton-Theoharis, Theoharis, Bull, Cosier, & Dempf-Aldrich, 2011![]() ; Garrison-Wade, Sobel, & Fulmer, 2007

; Garrison-Wade, Sobel, & Fulmer, 2007![]() ). A university has significant authority in carrying out research related to inclusive education through appropriate research methods to find research results relevant to problems in inclusive elementary schools. These results can be put into practice in inclusive elementary schools, both by GTs and inclusive elementary school management, to achieve inclusive elementary school goals. This condition is a form of university attention in helping inclusive elementary schools solve current problems.

). A university has significant authority in carrying out research related to inclusive education through appropriate research methods to find research results relevant to problems in inclusive elementary schools. These results can be put into practice in inclusive elementary schools, both by GTs and inclusive elementary school management, to achieve inclusive elementary school goals. This condition is a form of university attention in helping inclusive elementary schools solve current problems.

In addition to having substantial authority over research results, universities also have a great interest. They need to solve problems that occur in society, including inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools. As a result of problems in inclusive elementary schools, universities must recognize the need to design study programs or courses that can provide solutions to inclusive elementary schools (Tharp, 2018![]() ). Universities can help inclusive elementary schools in both academic and non-academic aspects (Helena, Borges, & Gonçalves, 2018

). Universities can help inclusive elementary schools in both academic and non-academic aspects (Helena, Borges, & Gonçalves, 2018![]() ), such as curriculum design, lesson plans, learning, and evaluation, and providing ways to maximize inclusive elementary school facilities and infrastructure.

), such as curriculum design, lesson plans, learning, and evaluation, and providing ways to maximize inclusive elementary school facilities and infrastructure.

As a facilitator, a university is a complete learning resource center and can be used by inclusive elementary schools. Universities and inclusive elementary schools need each other in the development of inclusive education (Angelides, 2008![]() ; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013

; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013![]() ). The problems faced by inclusive elementary schools provide information for universities to develop inclusive education subject topics. The results can be seen from graduates who are ready to teach in inclusive classrooms (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010

). The problems faced by inclusive elementary schools provide information for universities to develop inclusive education subject topics. The results can be seen from graduates who are ready to teach in inclusive classrooms (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010![]() ; Mag, Sinfield, & Burns, 2017

; Mag, Sinfield, & Burns, 2017![]() ). In practice, with the increasingly diverse problems faced by GTs, universities must continue to monitor and assist inclusive elementary schools as a form of academic and moral responsibility for the implementation of inclusive education.

). In practice, with the increasingly diverse problems faced by GTs, universities must continue to monitor and assist inclusive elementary schools as a form of academic and moral responsibility for the implementation of inclusive education.

A university's role as a mentor provides an opportunity for the institution to assist inclusive elementary schools in improving GT competence in implementing inclusive classroom learning. As a center for professional experts with high-quality academic backgrounds, universities can provide special professional assistance to assist GTs in solving inclusive practice problems in inclusive classrooms, as well as in inclusive schools on an ongoing basis. Human resources provision at universities, such as implementing special study programs to produce competent special assistant teachers, is one of the positive roles they can play in supporting inclusive practices (Garrison-Wade et al., 2007![]() ; Snyder, Hemmeter, & Fox, 2015

; Snyder, Hemmeter, & Fox, 2015![]() ).

).

Improving the competence of GTs and inclusive elementary school readiness in inclusive practice can be carried out by a university in its role as organizer. A university has broad authority and can connect networks between inclusive elementary schools and related parties who can subsequently support each other in the implementation of inclusive education (Lyons, Thompson, & Timmons, 2016![]() ; Malins, 2016

; Malins, 2016![]() ). This form of cooperation between each stakeholder can be an input for universities to develop relevant and systematic assistance programs so that they can provide mutual benefits. For example, seminars or training programs that universities can carry out to inclusive elementary schools on an ongoing basis can provide GTs with broad knowledge and insight. GTs can solve problems that occur in implementing learning in inclusive classrooms without losing direct knowledge sources from universities, which so far have not been assisted by the government.

). This form of cooperation between each stakeholder can be an input for universities to develop relevant and systematic assistance programs so that they can provide mutual benefits. For example, seminars or training programs that universities can carry out to inclusive elementary schools on an ongoing basis can provide GTs with broad knowledge and insight. GTs can solve problems that occur in implementing learning in inclusive classrooms without losing direct knowledge sources from universities, which so far have not been assisted by the government.

8. Conclusion and Recommendation

GTs' perception of the role of universities in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools has given great hope for the realization of a university's role in real terms. A university's role is expected to help solve the problem of the practice of inclusive education in elementary schools, which is still difficult to implement effectively and systematically. The role of a university in mentoring programs for inclusive elementary schools is as a developer of effective learning systems in inclusive classrooms and a provider of human resources who are competent in implementing inclusive education in inclusive elementary schools. This research is expected to be the basis for policymakers, especially in universities, to design appropriate and relevant mentoring programs for the problems faced by inclusive elementary schools.

Citation: | Rasmitadila; Megan Asri Humaira; Reza Rachmadtullah (2021). Teachers' Perceptions of the Role of Universities in Mentoring Programs for Inclusive Elementary Schools: A Case Study in Indonesia. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 8(3): 333-339. |

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(4), 401-416. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903.

Angelides, P. (2008). Patterns of inclusive education through the practice of student teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(3), 317-329. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110601103253 .

Bailey, R. W. (2013). Curriculum gatekeeping in global education: Global educators’ perspectives. University of South Florida.Graduate Theses and Disertations.

Betlem, E., Clary, D., & Jones, M. (2019). Mentoring the mentor: Professional development through a school-university partnership. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(4), 327-346. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2018.1504280 .

Burstein, N., Sears, S., Wilcoxen, A., Cabello, B., & Spagna, M. (2004). Moving toward inclusive practices. Remedial and Special Education, 25(2), 104-116. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325040250020501 .

Causton-Theoharis, J., Theoharis, G., Bull, T., Cosier, M., & Dempf-Aldrich, K. (2011). Schools of promise: A school district—university partnership centered on inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 32(3), 192-205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510366163 .

Domović, V., Vidović, V. V., & Bouillet, D. (2017). Student teachers’ beliefs about the teacher’s role in inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(2), 175-190. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1194571 .

Ellis, N. J., Alonzo, D., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (2020). Elements of a quality pre-service teacher mentor: A literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 92, 103072. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103072 .

Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., Smit, S., & Van Deventer, M. (2016). The idealism of education policies and the realities in schools: The implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(5), 520-535. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1095250 .

Frazier, D. K. (2018). Engaging high-ability students in literacy: A university and elementary school transformational partnership. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 30(4), 180-201.

Galloway, F. J., & Jenkins, J. R. (2009). The adjustment problems faced by international students in the United States: A comparison of international students and administrative perceptions at two private, religiously affiliated universities. NASPA Journal, 46(4), 661-673. Available at:https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.5038 .

Garrison-Wade, D., Sobel, D., & Fulmer, C. L. (2007). Inclusive leadership: Preparing principals for the role that awaits them. Educational Leadership and Administration: Teaching and Program Development, 19, 117-132.

Haryono, H., Syaifudin, A., & Widiastuti, S. (2015). Evaluation of inclusive education for children with special needs (Abk) in Central Java Province. Journal of Educational Research Unnes, 32(2), 124205.

Helena, M. M., Borges, M. L., & Gonçalves, T. (2018). Attitudes towards inclusion in higher education in a Portuguese university. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(5), 527-542. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1377299 .

Hoppey, D., & McLeskey, J. (2013). A case study of principal leadership in an effective inclusive school. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 245-256. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466910390507 .

Howell, P. B., Laman, T. T., Gnau, A., Bay-Williams, J., Brown, S., & Finch, J. (2021). Exploring teachers’ perspectives across multiple partnership schools: One university’s work to design mutually beneficial partnerships. School-University Partnerships, 14(1), 24-35.

Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(12), 1340-1356.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Lyons, W. E., Thompson, S. A., & Timmons, V. (2016). ‘We are inclusive. We are a team. Let's just do it’: Commitment, collective efficacy, and agency in four inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(8), 889-907. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1122841 .

Maddamsetti, J. (2018). Perceptions of pre-service teachers on mentor teachers’ roles in promoting inclusive practicum: Case studies in US elementary school contexts. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(2), 232-236. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2017.1422608 .

Mag, A. G., Sinfield, S., & Burns, T. (2017). The benefits of inclusive education: New challenges for university teachers. Paper presented at the MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences.

Mahajan, P., & Suresh, G. (2017). Only education is not enough: A necessity of all-inclusive services for technical education. International Journal of Advanced Research, 5(2017), 1246-1253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21474/ijar01/2878 .

Malins, P. (2016). How inclusive is “inclusive education” in the Ontario elementary classroom?: Teachers talk about addressing diverse gender and sexual identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 128-138. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.004 .

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative evaluation and research methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rahill, S. A., Norman, K., & Tomaschek, A. (2017). Mutual benefits of university athletes mentoring elementary students: Evaluating a university-school district partnership. School Community Journal, 27(1), 283-305.

Saniya, U. M., Widodo, H., Suyatno, & Santosa, A. B. (2020). The implementation of inclusive learning in muhammadiyah elementary School of Dadapan, Yogyakarta. American Journal of Education and Learning, 5(1), 123–133. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20448/804.5.1.123.133 .

Sharma, U., Armstrong, A. C., Merumeru, L., Simi, J., & Yared, H. (2019). Addressing barriers to implementing inclusive education in the Pacific. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(1), 65-78. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1514751 .

Snyder, P. A., Hemmeter, M. L., & Fox, L. (2015). Supporting implementation of evidence-based practices through practice-based coaching. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(3), 133-143. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121415594925 .

>Tharp, R. (2018). Teaching transformed: Achieving excellence, fairness, inclusion, and harmony. New York: Routledge.

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 319-356. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905 .

Wells, F. (2019). An exploration of elementary school principals’ perceptions of their role in creating inclusive school environments. Doctoral Dissertation, Houston Baptist University.

Williams, S. W., Watkins, K., Daley, B., Courtenay, B., Davis, M., & Dymock, D. (2001). Facilitating cross-cultural online discussion groups: Implications for practice. Distance Education, 22(1), 151-167. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791010220110 .

Winslade, M. (2016). Can an international field experience assist health and physical education pre-service teachers to develop cultural competency? Cogent Education, 3(1), 1264172. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2016.1264172 .

Zagona, A. L., Kurth, J. A., & MacFarland, S. Z. (2017a). Teachers’ views of their preparation for inclusive education and collaboration. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(3), 163–178. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417692969 .

Zagona, A. L., Kurth, J. A., & MacFarland, S. Z. (2017b). Teachers’ views of their preparation for inclusive education and collaboration. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(3), 163–178.

Zelina, M. (2020). Interviews with teachers about inclusive education. Acta Educationis Generalis, 10(2), 95-111. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2478/atd-2020-0012.

| Asian Online Journal Publishing Group is not responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability, etc. caused in relation to/arising out of the use of the content. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author of the article. |